Letters Home

Wartime Correspondence from the

Natale Bellantoni Papers

![My table— didn't give me chance to tidy up! New Caledonia [Note on back], circa 1945.](./assets/g9V18KYXpc/2019c21_030_001-for-web-2560x1992.jpeg)

“The Post Office, War, and Navy departments realize fully that frequent and rapid communication with parents, associates, and other loved ones strengthens fortitude, enlivens patriotism, makes loneliness endurable, and inspires to even greater devotion the men and women who are carrying on our fight far from home and from friends.”

The 1942 Annual Report of the United States Postmaster General

Throughout World War II, correspondence—particularly letters from loved ones—maintained the morale of troops fighting across the globe. The amount of post streaming back and forth across the Atlantic and Pacific oceans was massive, with the number of letters sent increasing each year. In 1945 alone, nearly three billion pieces of mail were exchanged between servicemembers and the friends and family who supported them on the home front. Wartime letters and diaries reveal that the mail call was one of the most cherished rituals of soldiers and sailors serving abroad. Craving news from home and words of encouragement, troops prized the letters that could, however briefly, allow them to escape the often harrowing and dangerous conditions in which they served.

While serving with the US Navy Seabees in the Pacific theater, Natale Bellantoni received a huge volume of mail from his family, as well as from his sweetheart and future wife, Irene Sztucinski. He responded with often delightfully illustrated letters that described his experiences in the South Pacific, including reports on his battalion’s work as well as anecdotes concerning the islands and peoples to which he was introduced on his journey. Housed at the Hoover Archives alongside his paintings and sketches, the letters provide the backdrop to Bellantoni’s artwork; reveal the love story of Nat and Irene; and show the profound effects of the war on Nat and his generation.

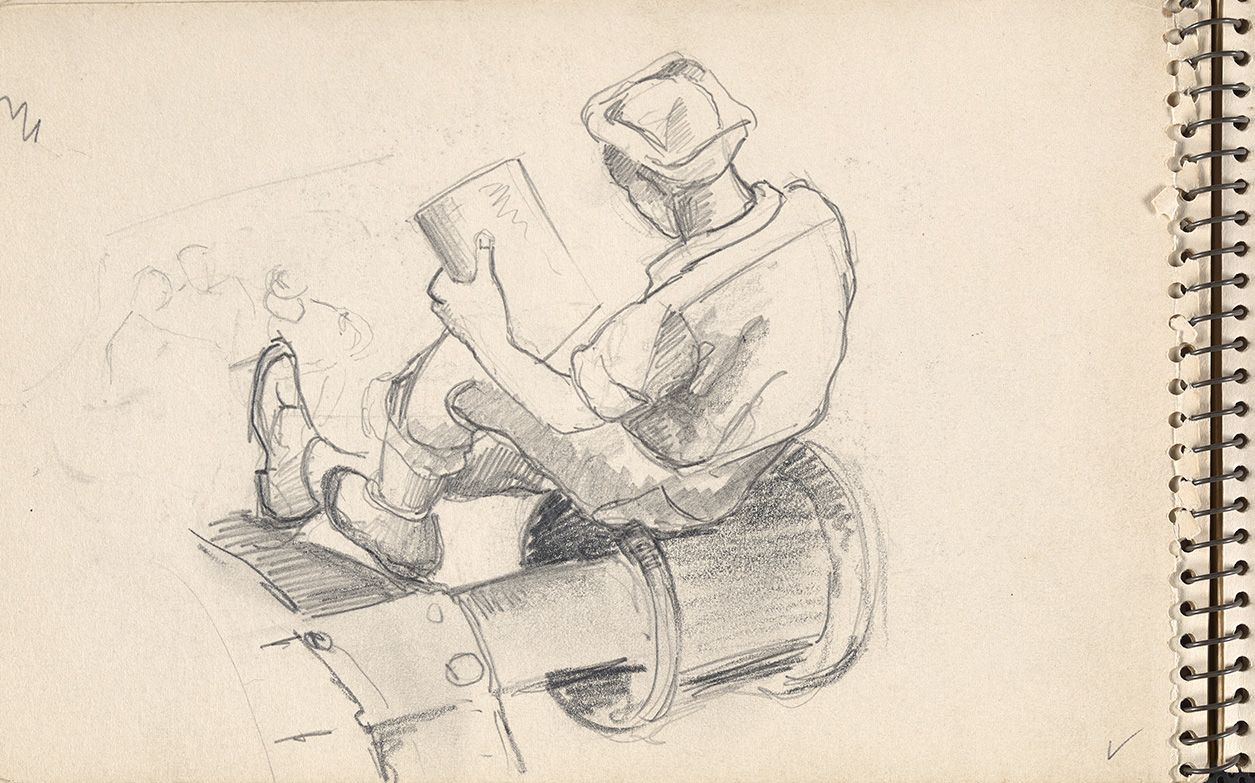

Untitled sketch of a sailor, by Natale Bellantoni, 1943–1945. Digital Record

From one of his two pocket sketchbooks.

Untitled sketch of a sailor, by Natale Bellantoni, 1943–1945. Digital Record

From one of his two pocket sketchbooks.

Missing Home

Natale Bellantoni hailed from a close-knit Italian family from the South End of Boston, Massachusetts, and throughout the war he corresponded with family members in order to hear the latest news. While Nat suffered from homesickness throughout his long journey across the Pacific, his longing for peace and home was perhaps most acute at holiday times.

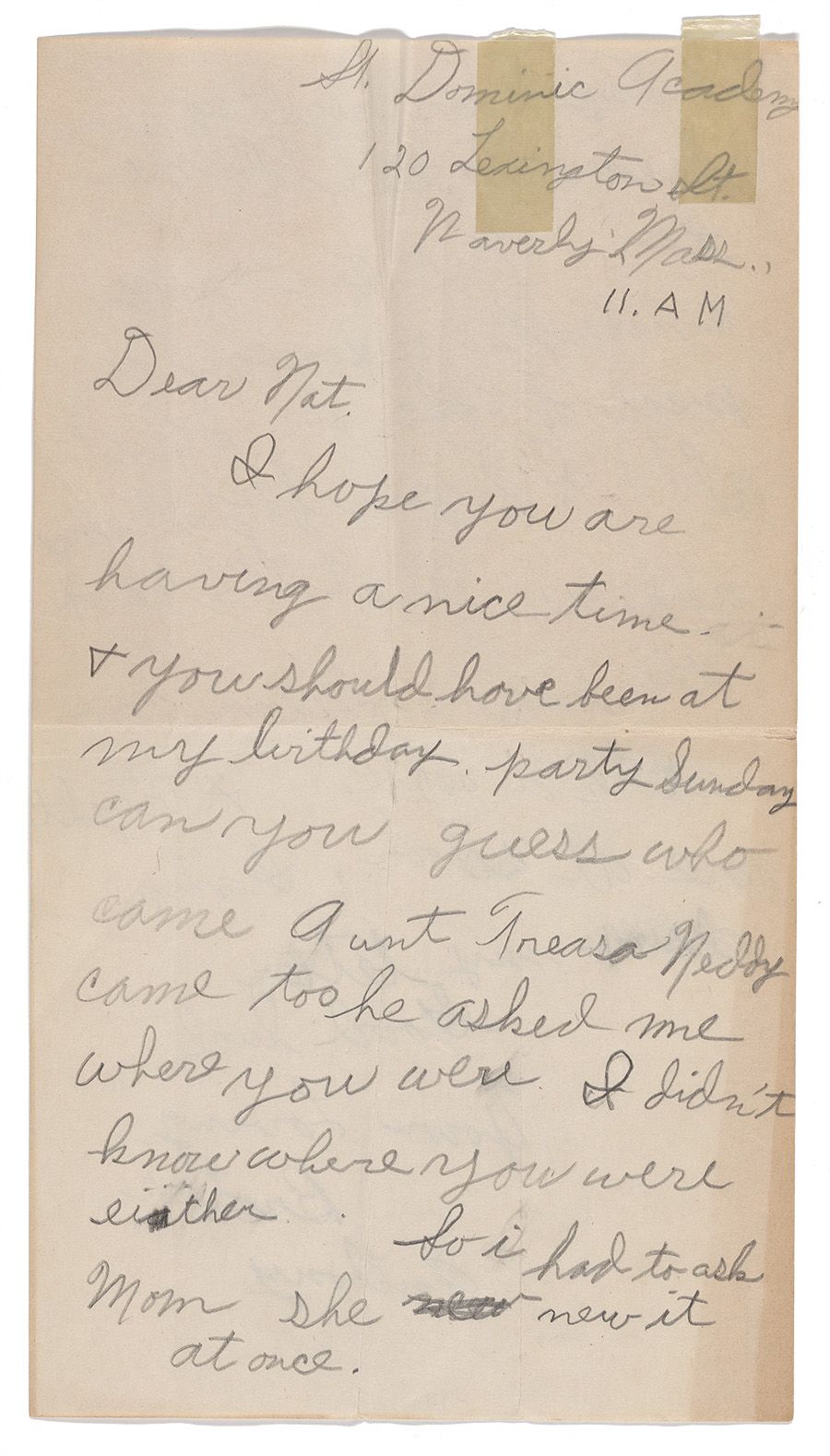

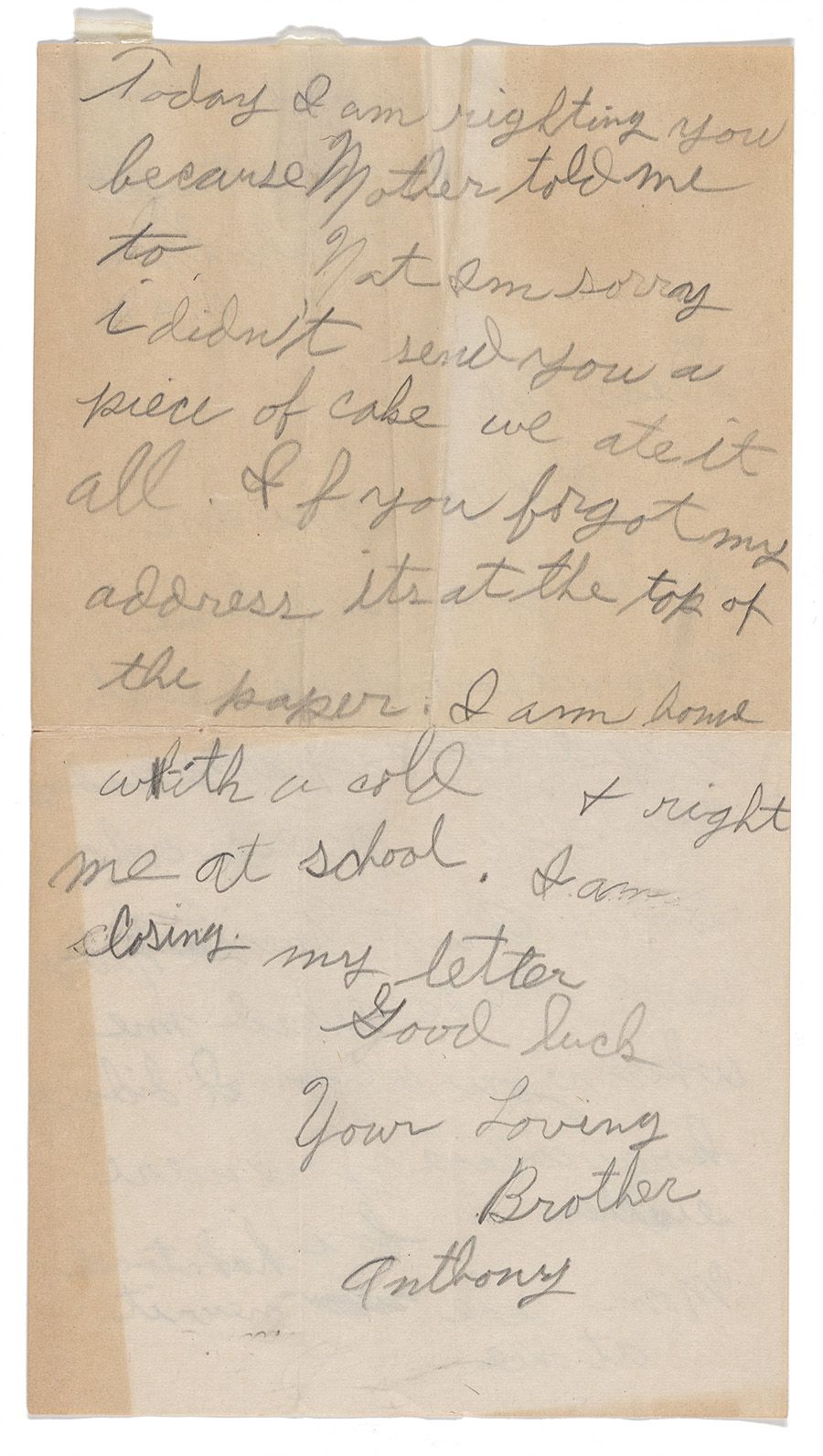

In addition to the comfort and company of home, he also missed the good, hearty food for which his family was known. In this letter, Nat’s little brother Anthony tells his sibling that he would have sent Nat some cake but it would have taken too long to reach him—and so Anthony had to eat it all himself!

Letter from Anthony Bellantoni to Natale Bellantoni, n.d. Digital Record

Letter from Anthony Bellantoni to Natale Bellantoni, n.d. Digital Record

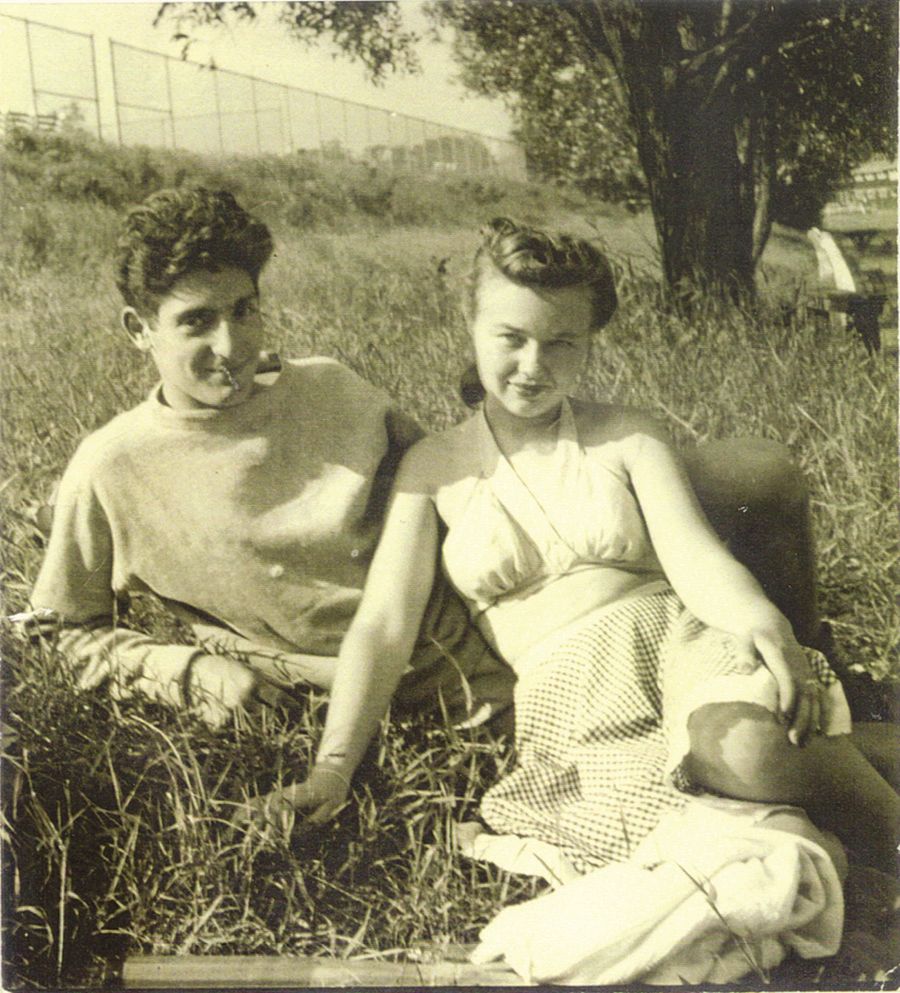

Natale Bellantoni and Irene Sztucinski, n.d.

Natale Bellantoni and Irene Sztucinski, n.d.

Natale Bellantoni, n.d.

Natale Bellantoni, n.d.

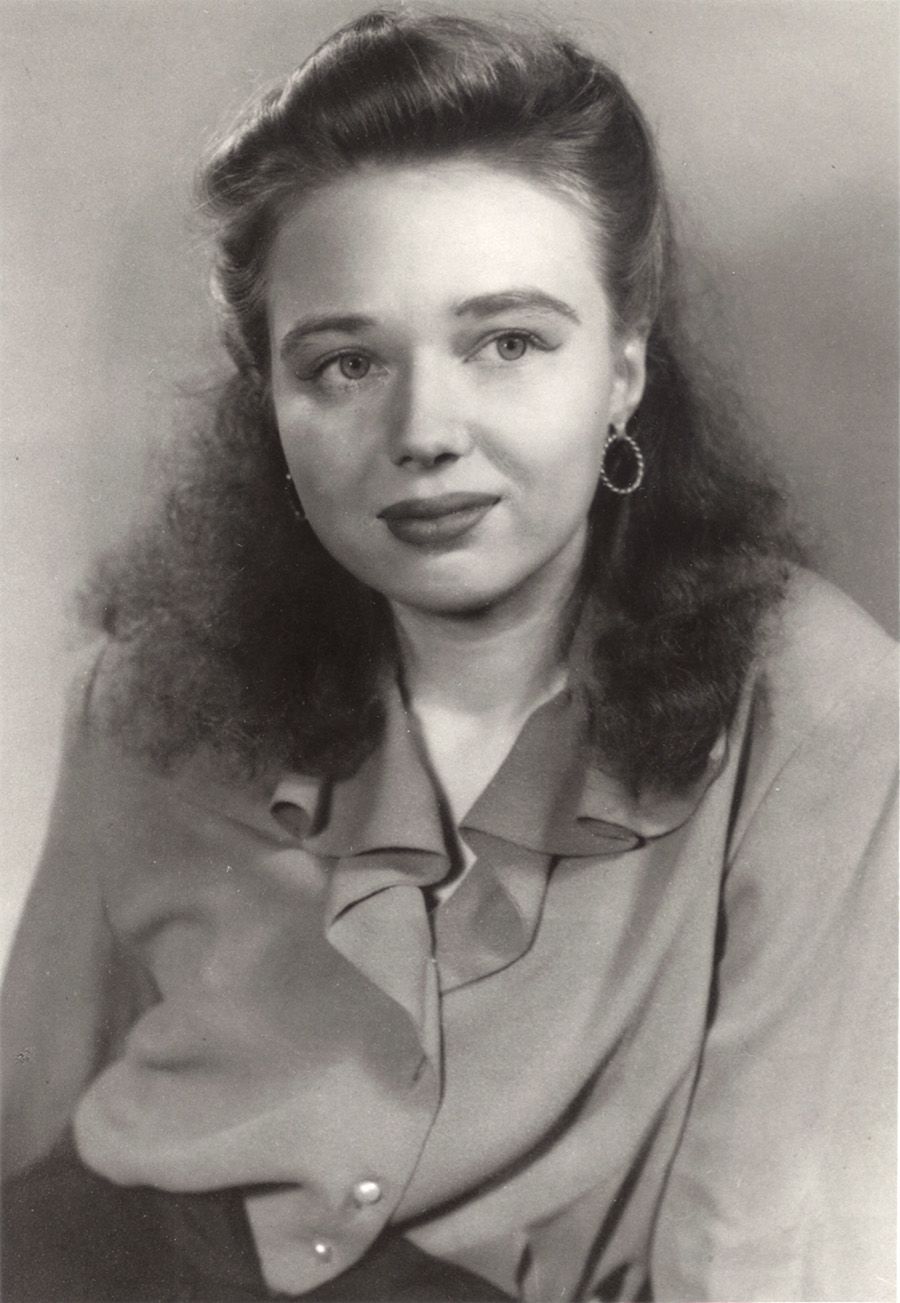

Irene Sztucinski, n.d.

Irene Sztucinski, n.d.

Love Letters

The majority of the letters held in the Natale Bellantoni papers at the Hoover Archives are written by Nat to his sweetheart, Irene Sztucinski. Nat met Irene when they were both art students at the Massachusetts School of Art directly prior to the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor. They shared a passion for art and creativity of all kinds and spent their early dating life painting, picnicking, and discussing the life that they would enjoy together after the war ended.

As worldwide conflict escalated, however, Nat began to consider whether or not to enlist. On October 7, 1942, Nat visited a US Navy recruiting station and joined the Navy Seabee unit for which he would eventually become the official artist.

His courtship of Irene would be put on hold for three years, three months, and three days as he journeyed across the Pacific and back. During this time, he and Irene would correspond faithfully, describing their experiences, fears, and wishes for marriage and the future.

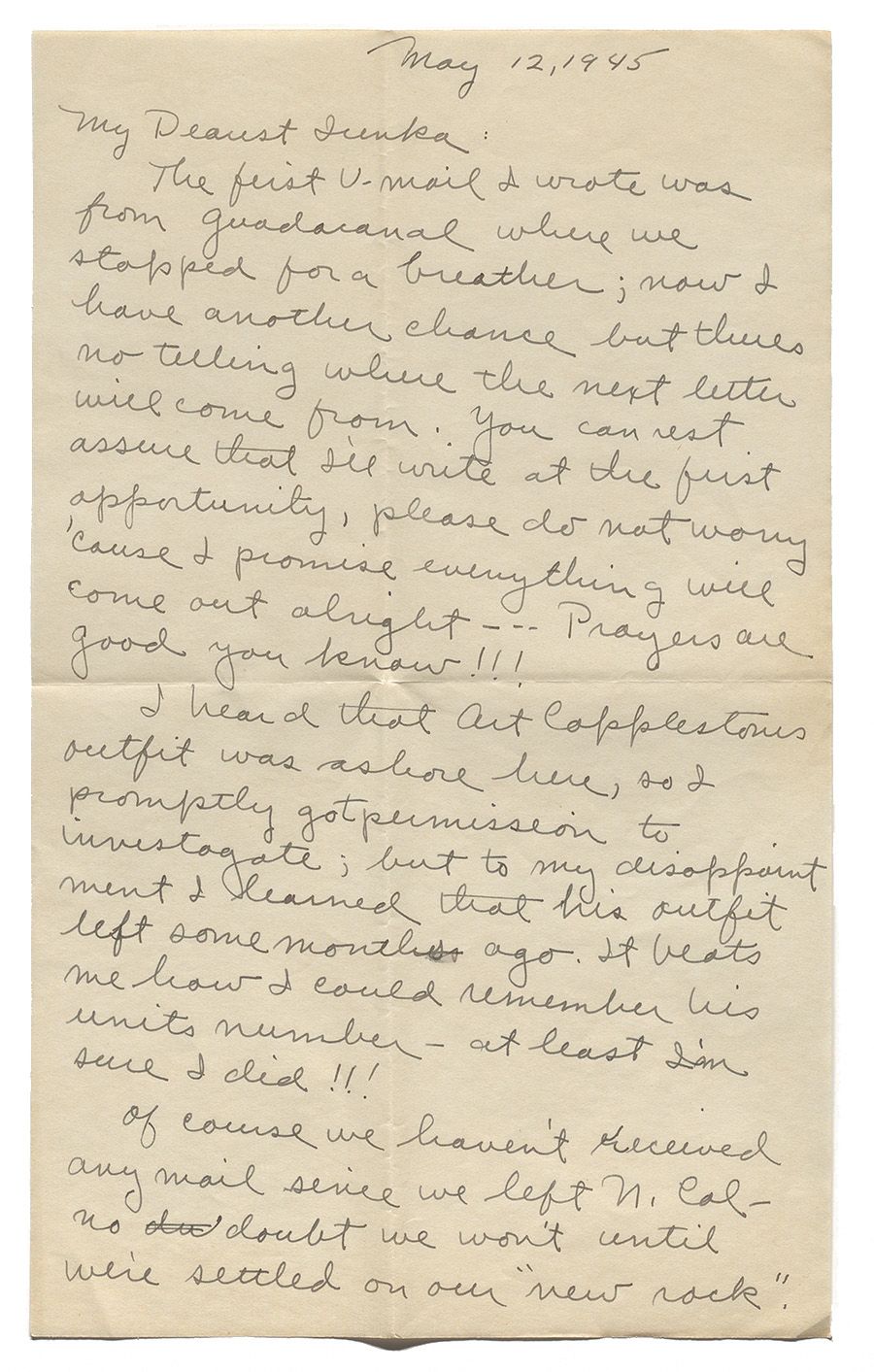

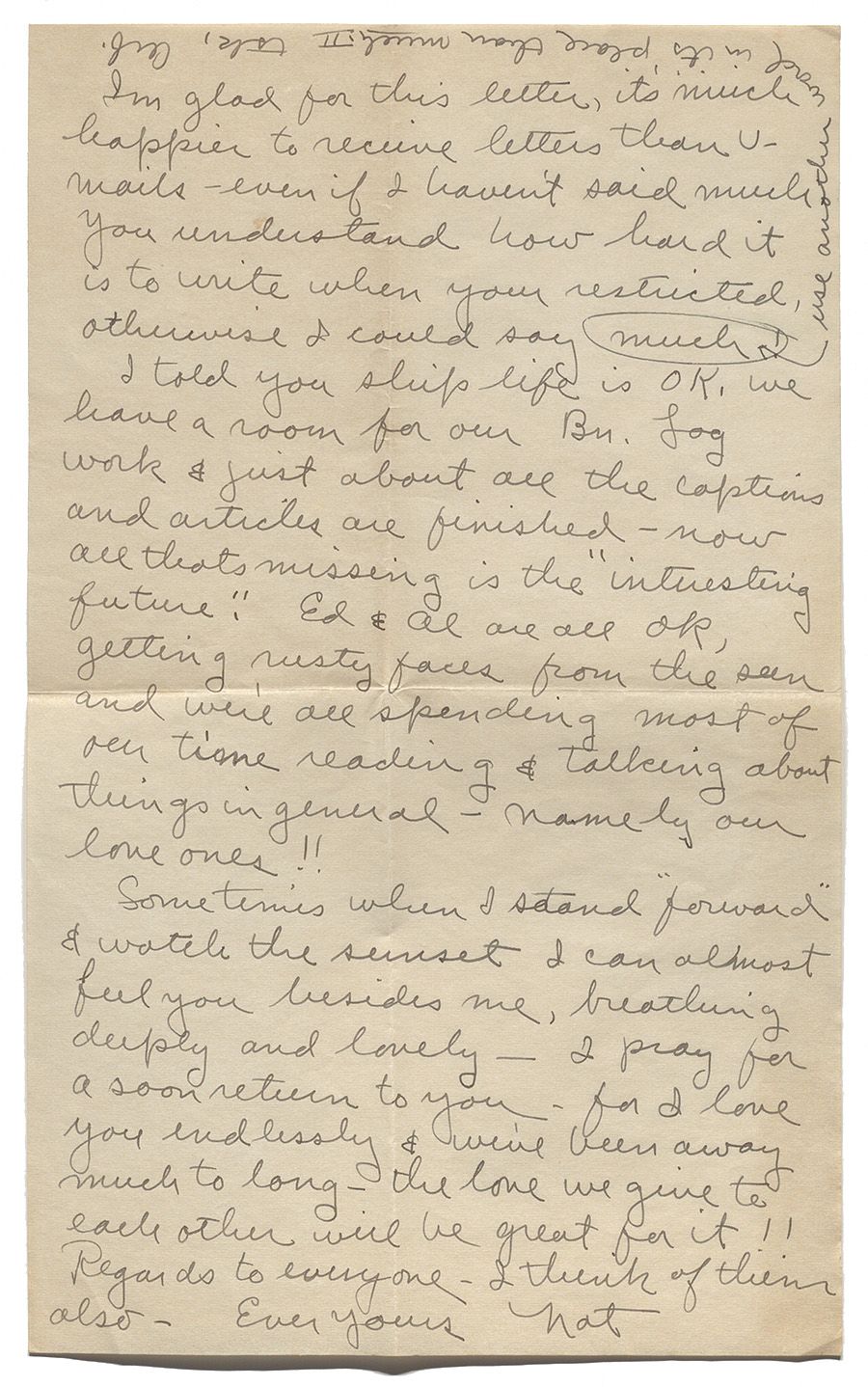

Letter from Natale Bellantoni to Irene Sztucinski, May 12, 1945. Digital Record

Letter from Natale Bellantoni to Irene Sztucinski, May 12, 1945. Digital Record

Mementos by Mail

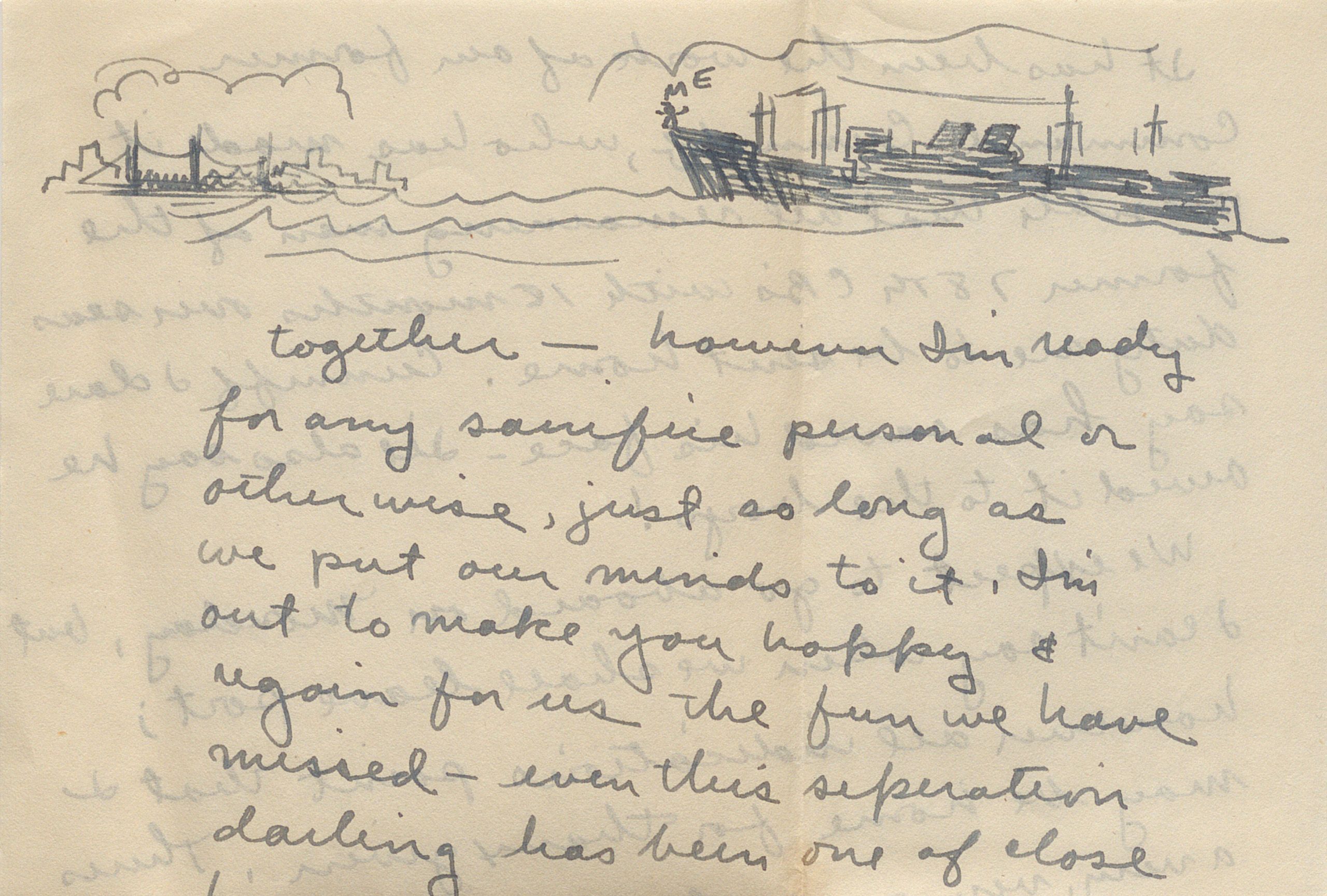

World War II letters abroad often included enclosures—pressed flowers, a lipstick kiss, a photograph, or other souvenirs—meant to personalize the letter for the receiver. As a prolific artist, Nat often included sketches of his surroundings or the people he met during his travels across the ocean.

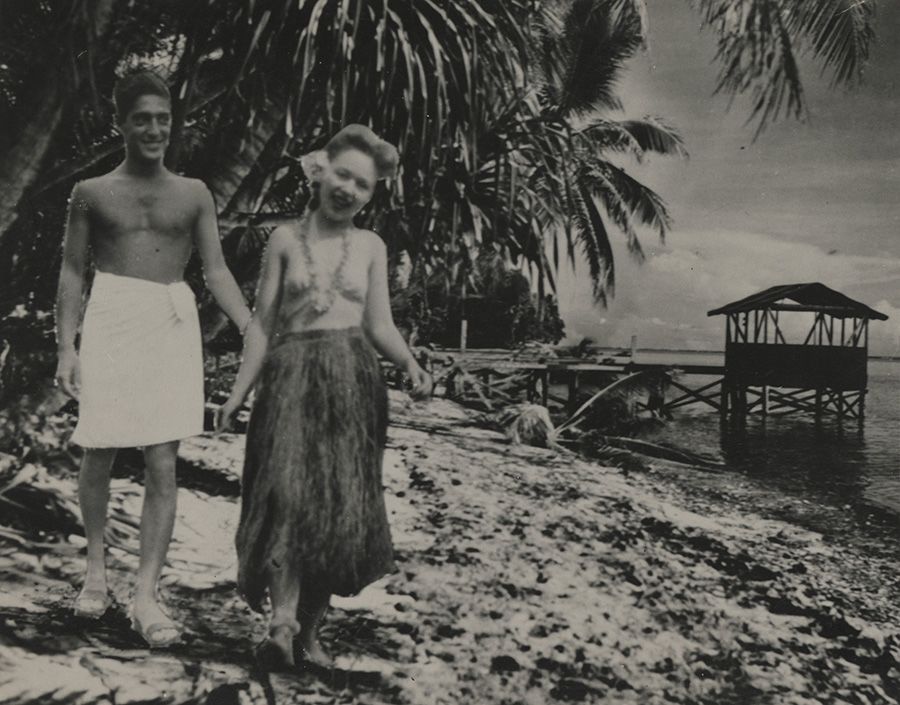

One of the most inventive enclosures included in the Natale Bellantoni papers is an example of trick photography. While in New Guineae, Nat bought a grass skirt at a local market, sent it to Irene, and asked her to send him a picture of herself wearing it. Meanwhile, he also bought a locally made sarong and had a battalion mate take a picture of him wearing it on an island beach. With the help of his good friend, the battalion photographer Edward Keegan, Nat then spliced his picture together with that of Irene in the grass skirt. Voilà! Nat and Irene were reunited, albeit via darkroom magic if not yet in person.

Letter from Natale Bellantoni to Irene Sztucinski [cropped], November 3, 1945. Digital Record

Letter from Natale Bellantoni to Irene Sztucinski [cropped], November 3, 1945. Digital Record

Photomontage of Natale Bellantoni and Irene Sztucinski, 1944–1945.

Photomontage of Natale Bellantoni and Irene Sztucinski, 1944–1945.

Censorship

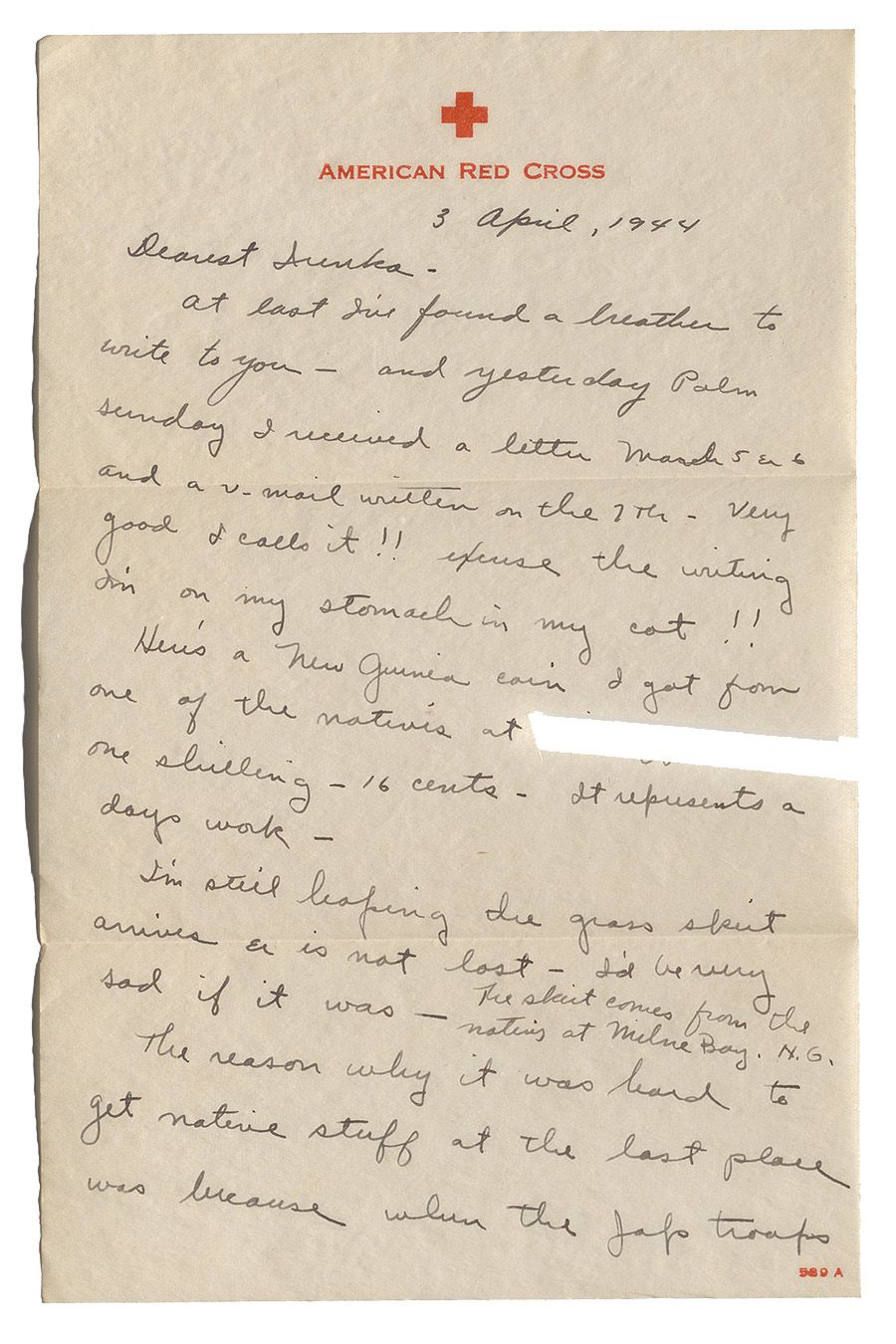

Throughout World War II, the letters written by enlisted men were censored by ranking officers, who read them to ensure that no useful information would fall into enemy hands should mail be intercepted. In particular, censors checked letters to make sure servicemen made no mention of their geographic location, nor any indication of the strength or numbers of their battalions. Censors would cut out words or sentences or redact portions of the letters with heavy ink. Additionally, many letters written in foreign languages would simply not be sent because they rarely could be properly censored—often an enormous problem for the many troops born into immigrant families.

In this letter to Irene written on American Red Cross stationery, Nat mentions the specifics of his location in New Guinea; the place name has been cut out by the censor.

Letter from Natale Bellantoni to Irene Sztucinski, April 3, 1944. Digital Record

Letter from Natale Bellantoni to Irene Sztucinski, April 3, 1944. Digital Record

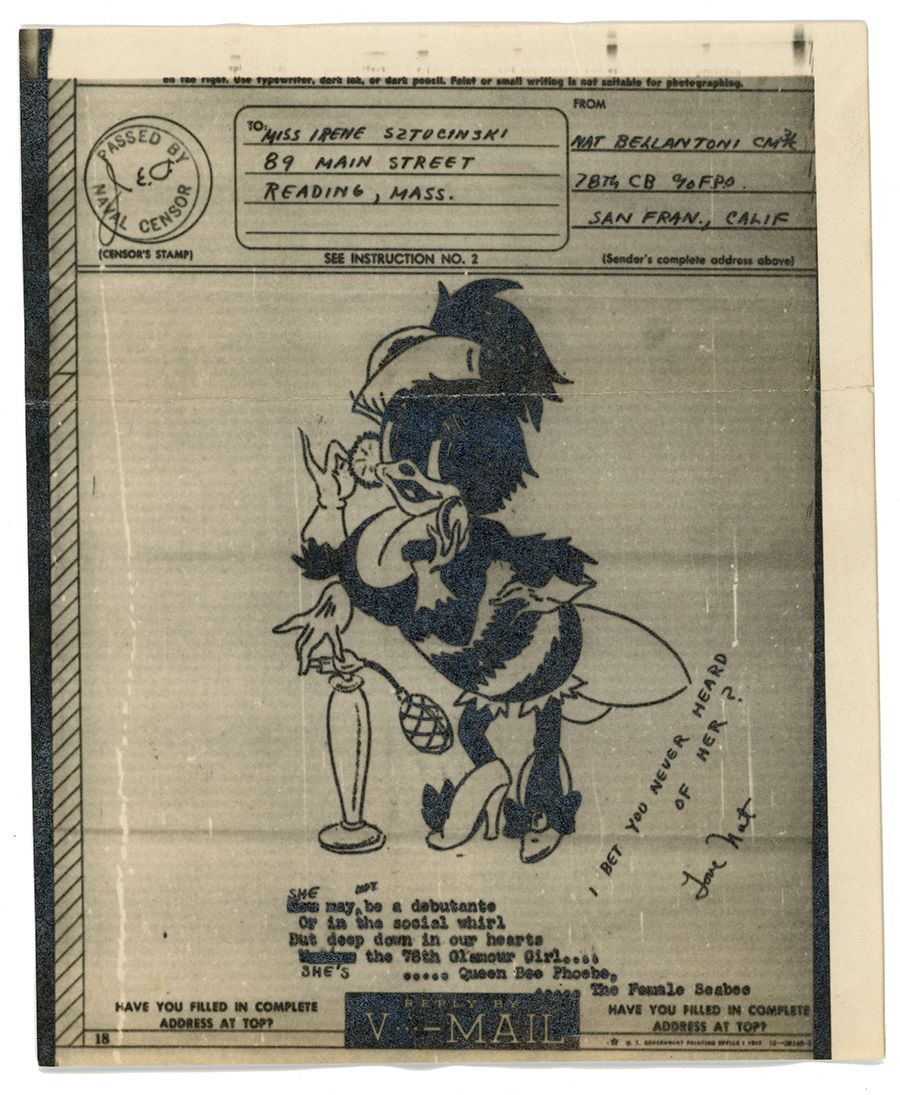

Sometimes, censors would redact parts of letters that contained lewd or graphically sexual content. This flirty lady Seabee, however, has been stamped “passed by naval censor.”

V-Mail from Natale Bellantoni to Irene Sztucinski, n.d. Digital Record

Phoebee, the female Seabee, was created by Hank Porter at Walt Disney Studios in 1944 at the request of Seabees looking for a pin-up girl bee to represent their wives and sweethearts. Nat liked her enough to send Irene his version with this caption below: She may not be a debutante / Or in the social whirl / But deep down in our hearts / She's the 78th's Glamour Girl . . . . Queen Bee Phoebe, The Female Seabee

V-Mail from Natale Bellantoni to Irene Sztucinski, n.d. Digital Record

Phoebee, the female Seabee, was created by Hank Porter at Walt Disney Studios in 1944 at the request of Seabees looking for a pin-up girl bee to represent their wives and sweethearts. Nat liked her enough to send Irene his version with this caption below: She may not be a debutante / Or in the social whirl / But deep down in our hearts / She's the 78th's Glamour Girl . . . . Queen Bee Phoebe, The Female Seabee

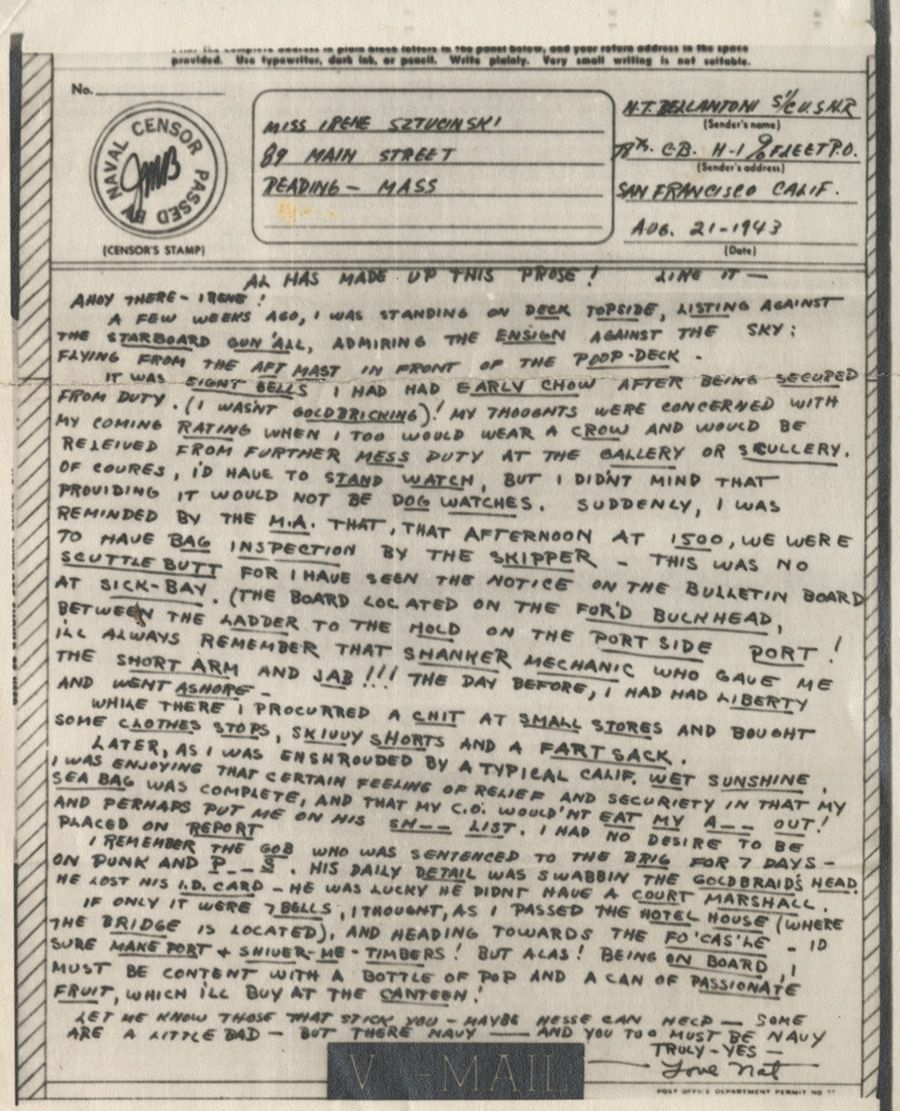

In an attempt to embed intimate or personal content into a letter that must pass the censor, servicemen would often use codes or ciphers. The underlined words in this letter to Irene indicate a code known to the two of them. Nevertheless, it passed the censor. Since Nat was never allowed to tell Irene where he was, his return address invariably read: 78th N.C.B. c/o F.P.O. San Fran, Calif.

V-Mail from Natale Bellantoni to Irene Sztucinski, August 21, 1943. Digital Record

V-Mail from Natale Bellantoni to Irene Sztucinski, August 21, 1943. Digital Record

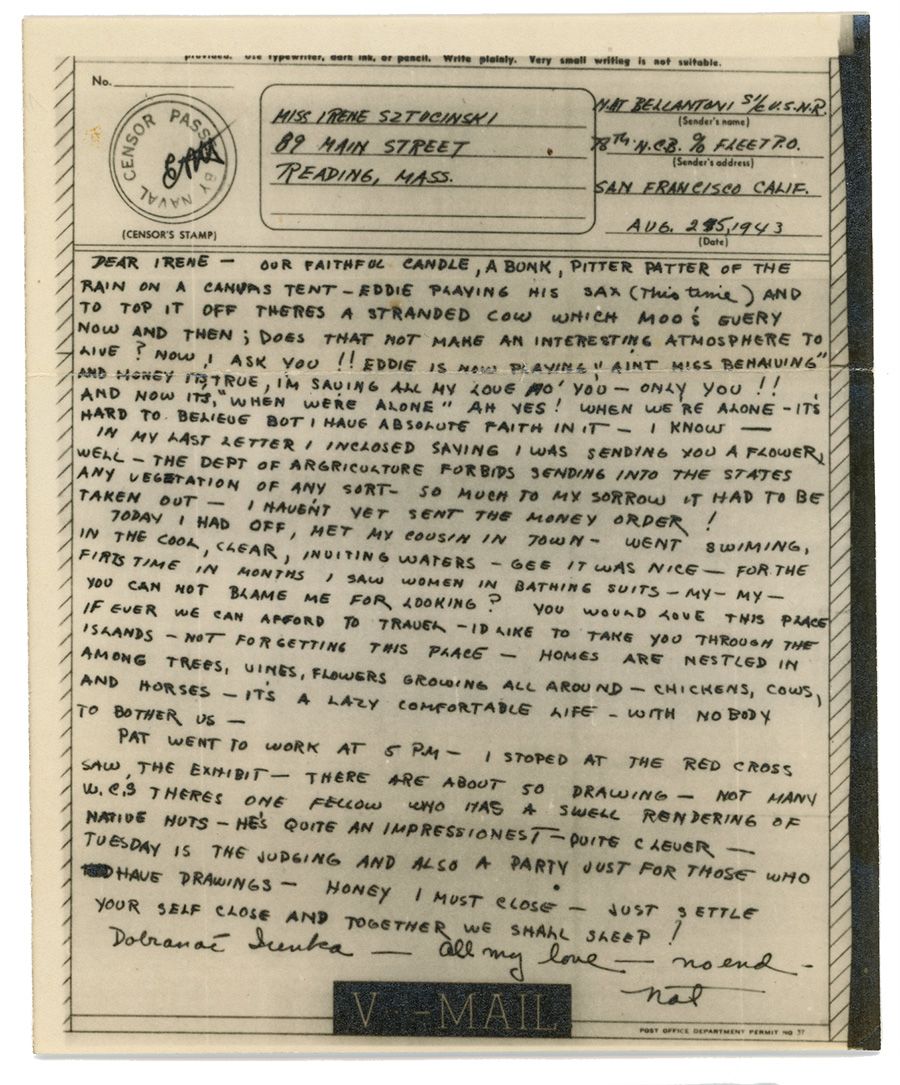

V-Mail from Natale Bellantoni to Irene Sztucinski, August 25, 1943. Digital Record

V-Mail from Natale Bellantoni to Irene Sztucinski, August 25, 1943. Digital Record

Reach Your Boy Overseas by V-Mail, by Jes Wilhelm Schlaikjer, issued by the United States Army Recruiting Publicity Bureau, 1942. Poster Collection, US 7304, Hoover Institution Archives

Reach Your Boy Overseas by V-Mail, by Jes Wilhelm Schlaikjer, issued by the United States Army Recruiting Publicity Bureau, 1942. Poster Collection, US 7304, Hoover Institution Archives

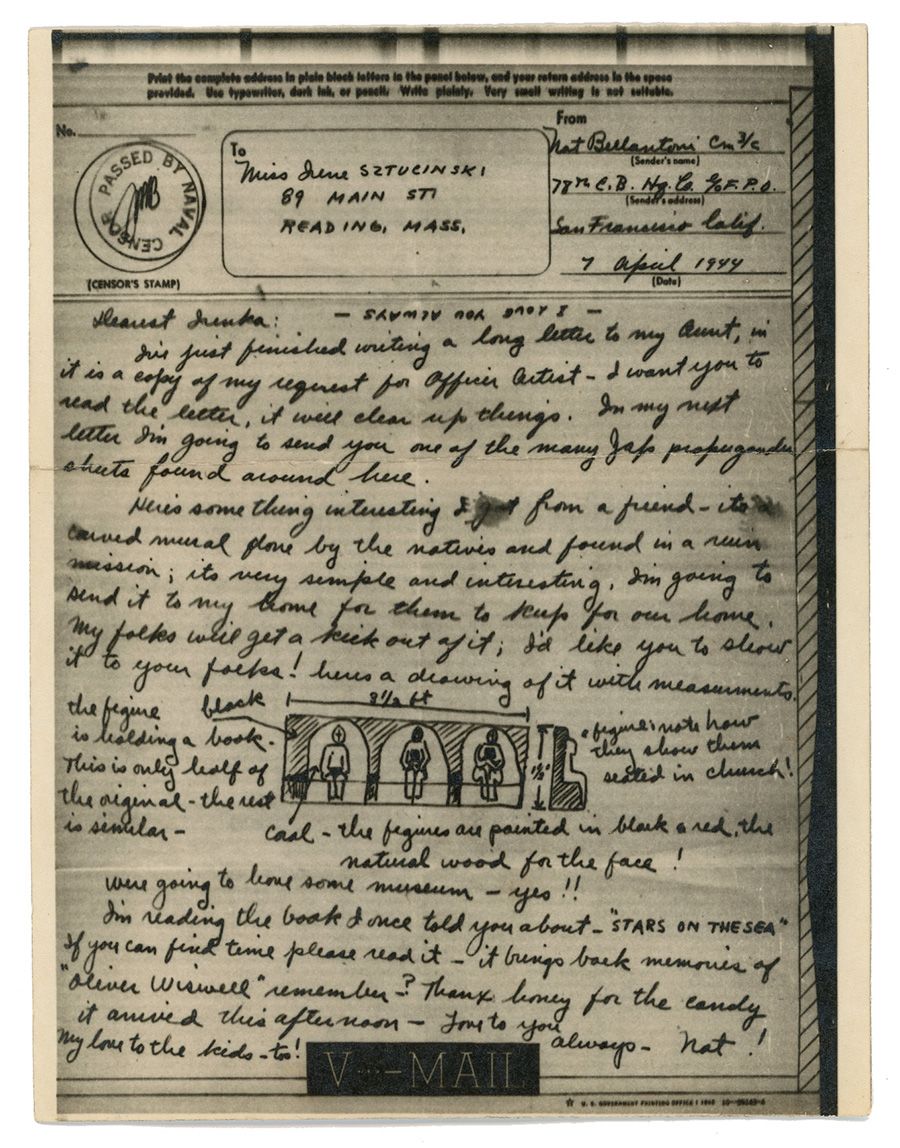

V-Mail from Natale Bellantoni to Irene Sztucinski, April 7, 1944. Digital Record

V-Mail from Natale Bellantoni to Irene Sztucinski, April 7, 1944. Digital Record

V-mail

At the beginning of the war, a letter sent from the United States to destinations abroad could take weeks to arrive. Nat’s correspondence to his family and Irene would travel over 14,000 miles, and often responses were slow to appear because of transport difficulty, bad weather, or logistical snafus. Soldiers and sailors who suffered through prolonged waiting for mail often felt anxious and lonely for home.

On June 1, 1942, the US government tried to alleviate the problem of slow postal delivery by introducing “V-mail,” short for “Victory mail,” a system of microphotography aimed to drastically reduce the space needed to transport mail, thus freeing up room for other valuable supplies. Letters were photographed on microfilm and then the film was transported by air to a postal station close to the intended recipients. Once there, letters were reproduced and censored before delivery. Stateside, there were three giant postal centers in New York, Chicago, and San Francisco that had the machinery and setup to process V-mail. This efficient and expeditious method of postal delivery was free to servicemembers. On the home front, posters promoted V-mail as the patriotic choice at the post office: shrinking the bulk of mail bags meant that planes headed overseas could carry more food and ammunition for troops. Around 1,600 letters could fit on a single 100 foot roll of 16mm film, so the equivalent of thirty-seven mail bags could fit within one V-mail bag.

Though fast and efficient, V-mail also had drawbacks: the standardized stationery limited word length and depersonalized the epistolary experience. Senders could not include creative enclosures—the lipstick kiss would jam government-contracted Kodak microphotography machines. Often the ink used to reproduce the original V-mail message would be blurry and hard to read. Nevertheless, between June 1942 and November 1945, more than one billion V-mails were processed by the United States Postal Service. Nat and Irene would frequently use V-mail messages, especially when important news needed to be reported quickly. Longer, more conversational letters were usually written by hand and sent by slower, but more private, first-class mail.

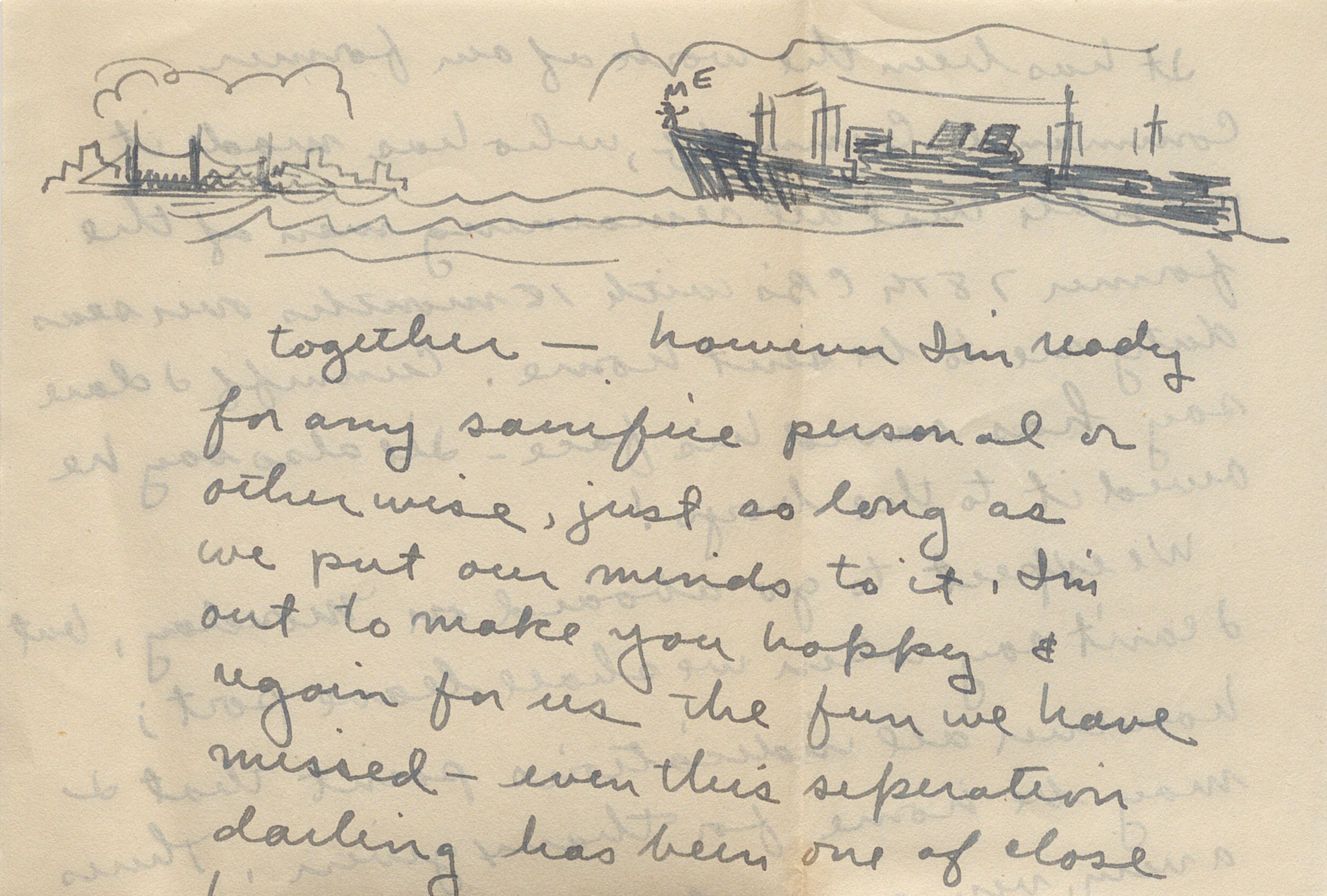

Coming Home

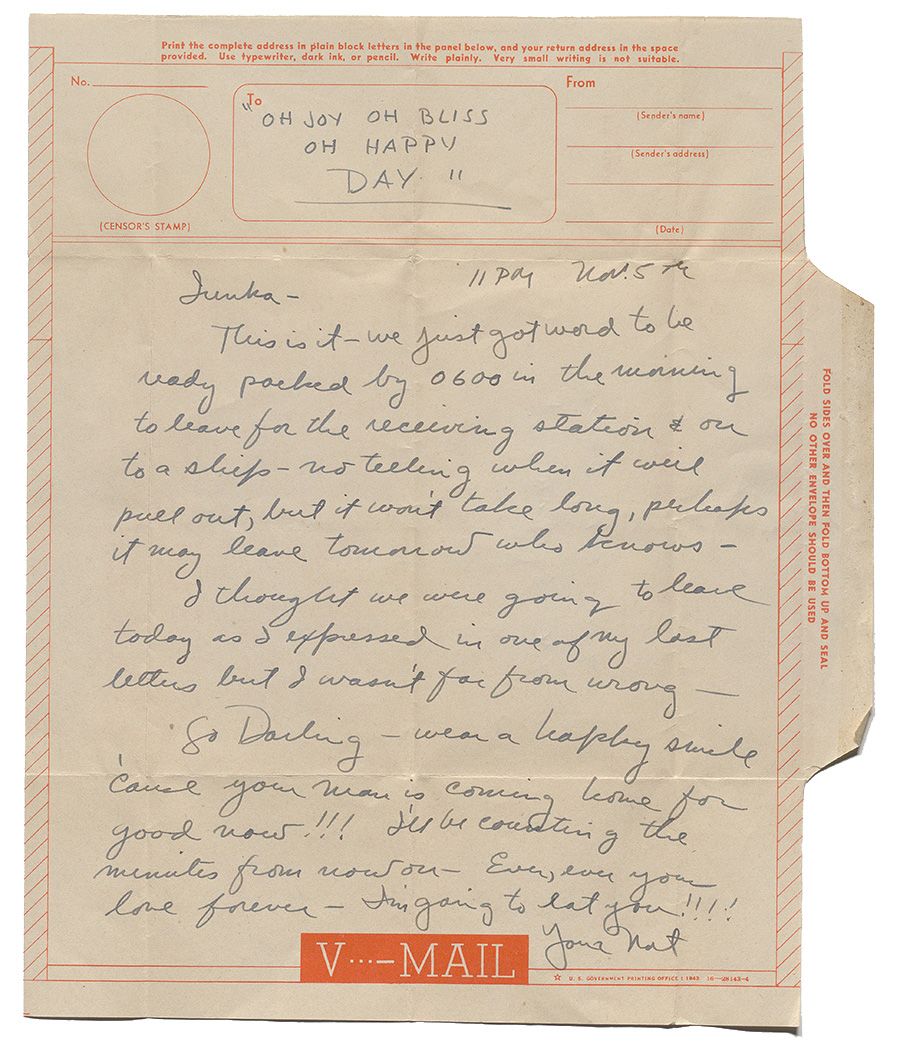

During the war one letter was prized above all others: the announcement that a serviceman was coming home safely, and soon. In this letter, headed “OH JOY OH BLISS OH HAPPY DAY,” Nat reports to Irene that he has received word that his battalion will be leaving the Pacific theater for home.

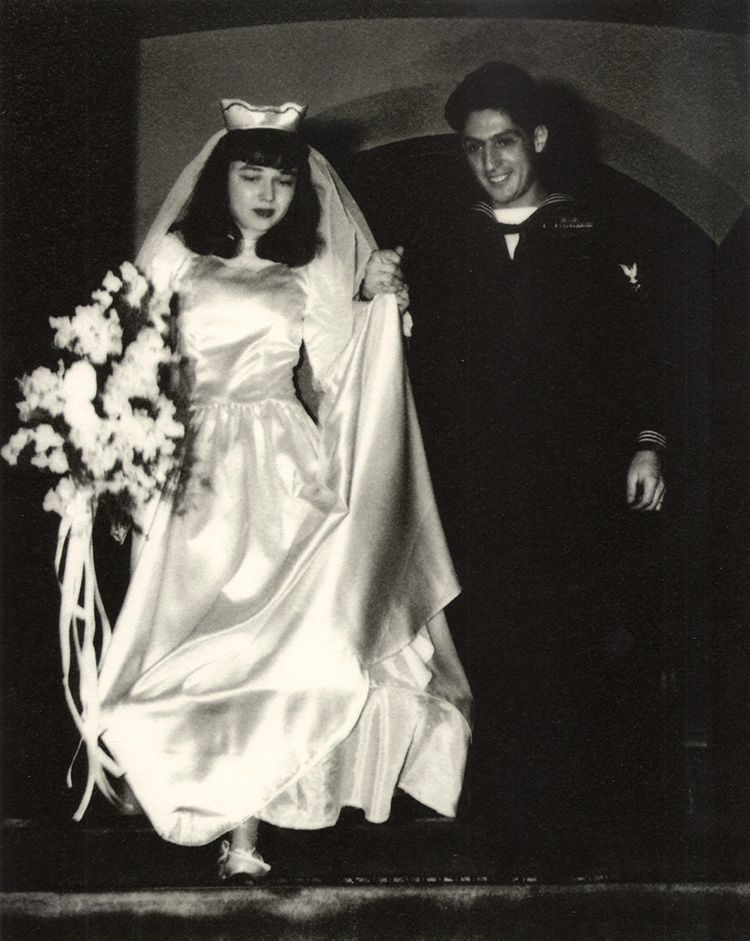

After spending years apart and writing hundreds of letters, Nat and Irene were reunited. They married on January 6, 1946, four days before Nat was formally discharged from the US Navy. Irene’s love letters had sustained Nat throughout his long months on New Caledonia, New Guinea, Los Negros, Manus, Ponam, and Okinawa. After the war, the couple settled in Reading, Massachusetts, and raised three children. Nat continued to work as an artist and art director for the rest of his career.

Natale Bellantoni’s letters, paintings, and sketches were acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 2017. The collection documents the personal experiences of one of the US Navy’s most gifted artists, who is just one representative of an entire generation of young American soldiers serving courageously in the dangerous conditions of World War II. The archives—in particular the lovingly composed letters sent to and from family and loved ones—also stand testament to the strength and fortitude of the mothers, fathers, brothers, sisters, friends, and sweethearts who waited and worried on the home front. Morale could certainly not be maintained, nor victory assured, without the billions of letters sent to encourage, entertain, and support the men and women far from the comforts of home.

Letter on V-mail paper from Natale Bellantoni to Irene Sztucinski, November 5, 1945. Digital Record

Letter on V-mail paper from Natale Bellantoni to Irene Sztucinski, November 5, 1945. Digital Record

Irene and Natale Bellantoni on their wedding day, January 6, 1946.

Irene and Natale Bellantoni on their wedding day, January 6, 1946.

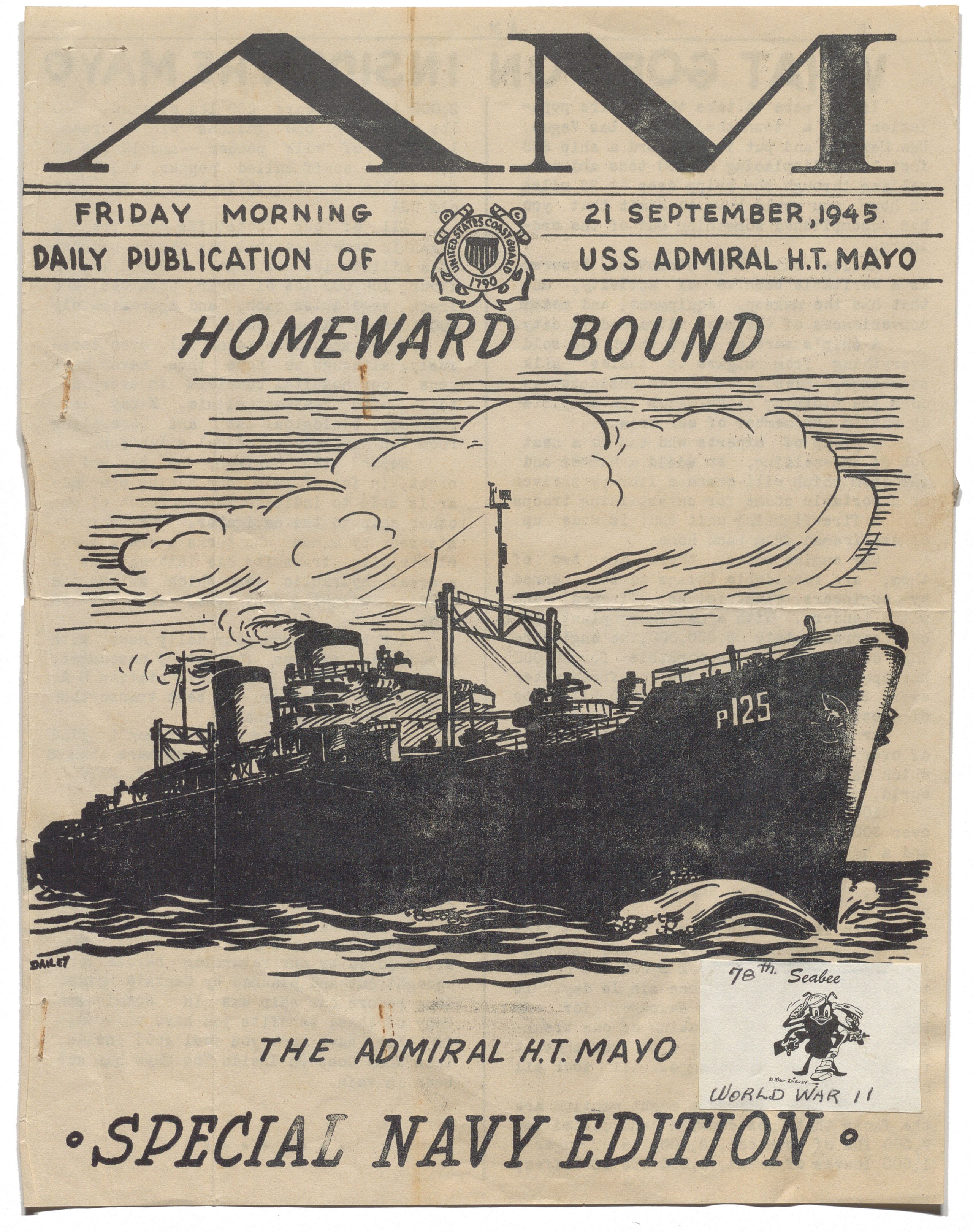

The Admiral H. T. Mayo Homeward Bound Special Navy Edition, September 21, 1945. Digital Record

The Admiral H. T. Mayo Homeward Bound Special Navy Edition, September 21, 1945. Digital Record

Unless otherwise noted, all collection material shared in this presentation is part of the Natale Bellantoni Papers housed at the Hoover Institution Library & Archives, Stanford University.

The Hoover Institution Library & Archives has placed copies of these works online for educational and research purposes. If you would like to use any of these works, you are responsible for making your own legal assessment and securing any necessary permission. If you have questions about this resource or have concerns about the inclusion of an item, please contact the Hoover exhibits team:

Contact Us

For more information about rights and permissions please visit,https://www.hoover.org/library-archives/collections/get-help/right[a]-and-permissions.

© 2022 by the Board of Trustees of Leland Stanford Junior University.