Fighting for Freedom

Dissident Struggles for Democracy

“Communism is an evil thing. It is contrary to the spiritual, moral, and material aspirations of man. These very reasons give rise to my conviction that it will decay and die of its own poisons. But that may be many years away and, in the meantime, we must be prepared for a long journey.”

Herbert Hoover, "The Year Since the Great Debate" speech, January 27, 1952

Resistance to tyranny and authoritarian regimes has always been a special focus of the Hoover Institution Library & Archives collecting, research, and publications. One emphasis for Hoover’s work has been the dissident movements in the Soviet Union and its Eastern European satellite states.

By the 1980s, resistance against communist regimes grew into popular protests, as the forces of freedom began to gain the upper hand. The year 1989 was the turning point, symbolized by the fall of the Berlin Wall in November. The transitions to democracy in the former Soviet bloc countries continued into the 1990s.

China, meanwhile, introduced a form of capitalist economy in the 1980s, but in 1989 its communist rulers declared martial law and ruthlessly suppressed a nascent democracy movement, massacring students and others protesting in Tiananmen Square.

Germany

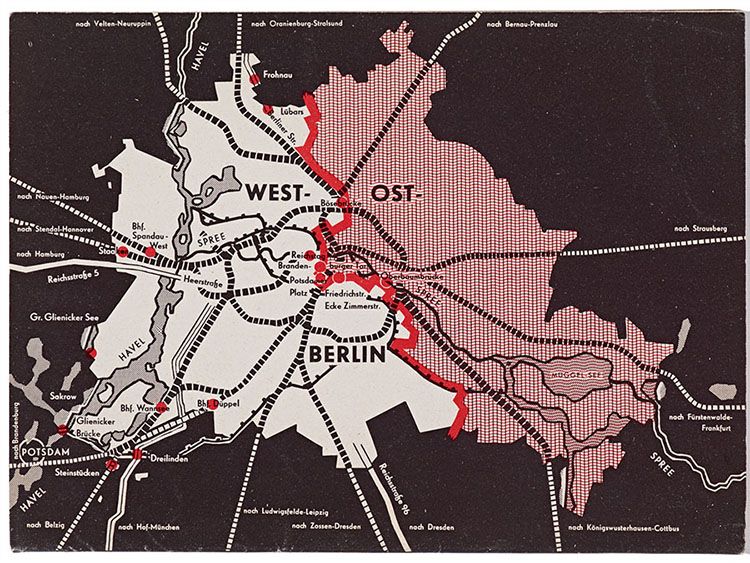

Freie Stadt Zwischen Stacheldraht (Free City between barbed wire), May 1959. Pamphlet Collection, Hoover Institution Library

Freie Stadt Zwischen Stacheldraht (Free City between barbed wire), May 1959. Pamphlet Collection, Hoover Institution Library

The Berlin Wall

The German Democratic Republic (GDR), commonly known as East Germany, began to erect the Berlin Wall—in secret and in haste—on the night of August 13, 1961.

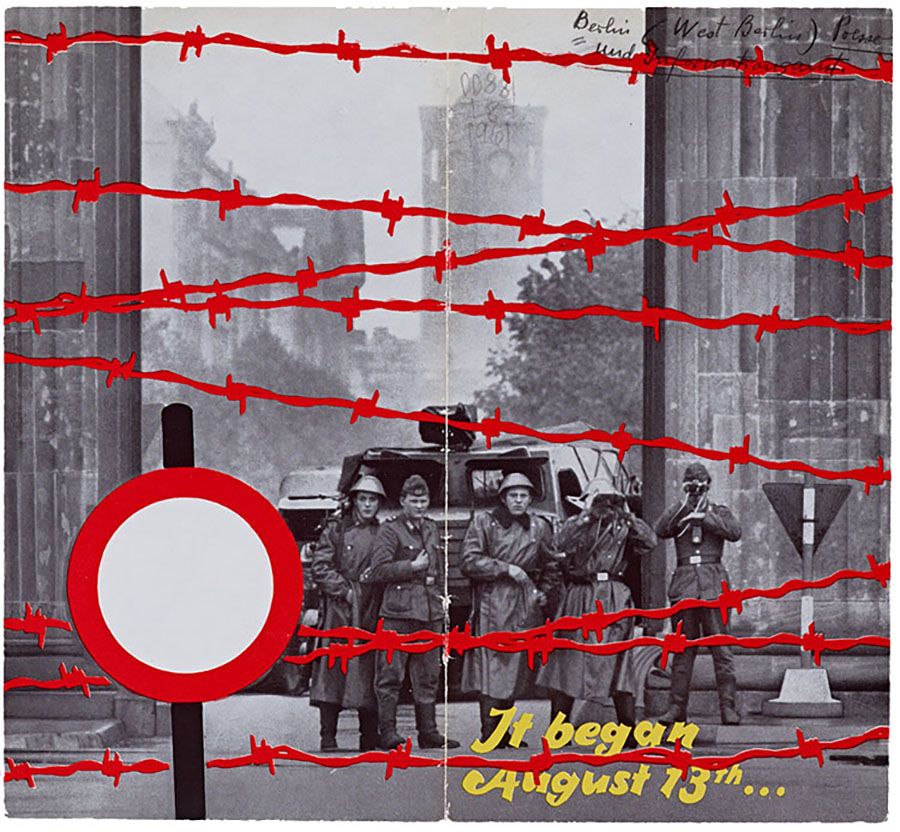

It began August 13th... The Press and Information Office of Berlin, 1961. Pamphlet Collection, Hoover Institution Library

It began August 13th... The Press and Information Office of Berlin, 1961. Pamphlet Collection, Hoover Institution Library

GDR propaganda maintained that the wall was necessary to protect East Germany from external enemies, but in fact its purpose was to put a stop to the mass exodus of its citizens—more than 2.5 million residents of East Germany had fled through Berlin to the West after Germany became formally divided in 1949.

The wall was the most visible symbol separating the people of East Berlin from the economic and political freedoms available in the democratic West.

Building the Berlin Wall

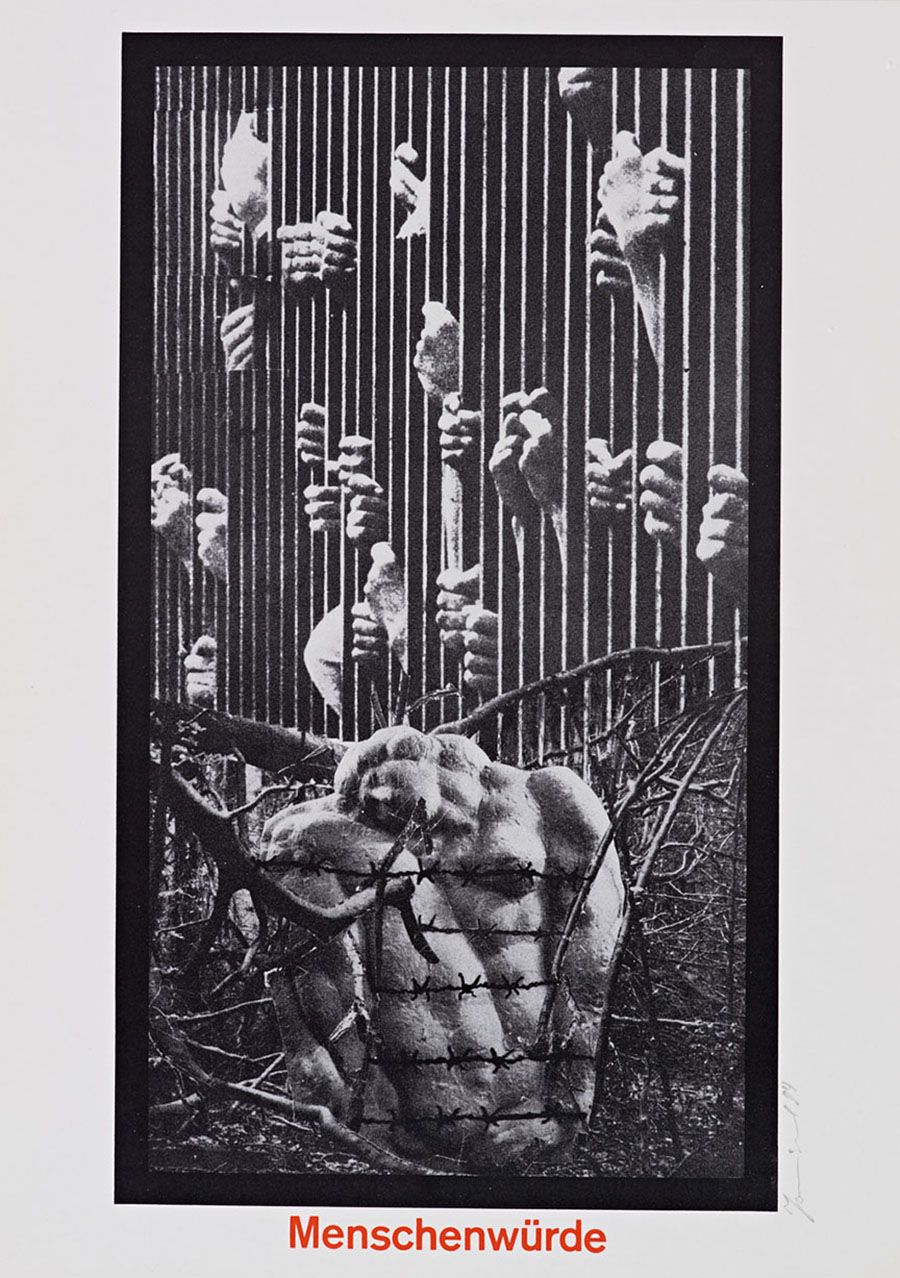

The wall consisted of sixty-six miles of concrete segments and forty-one miles of barbed-wire fencing and was guarded by more than three hundred watchtowers. Daring attempts to cross from East to West Berlin punctuated the Cold War. In all, some five thousand people successfully escaped to the West, while an estimated two hundred people were killed attempting to do so.

Menschenwürde (Human dignity), by Wolfgang Janisch, 1984. Wolfgang Janisch Papers, Hoover Institution Archives

Menschenwürde (Human dignity), by Wolfgang Janisch, 1984. Wolfgang Janisch Papers, Hoover Institution Archives

Ronald Reagan at Checkpoint Charlie, July 11, 1982. Berlin: Checkpoint Charlie, 1946–1989: Photographic Portfolio, ca. 1990, Hoover Institution Archives

Ronald Reagan at Checkpoint Charlie, July 11, 1982. Berlin: Checkpoint Charlie, 1946–1989: Photographic Portfolio, ca. 1990, Hoover Institution Archives

“Tear Down This Wall!”

In 1983, President Ronald Reagan called communism “the focus of evil in the modern world” and labeled the Soviet Union an “evil empire.” Reagan's decision to begin nuclear arms control negotiations with the Soviet government did not inhibit him from continuing to deliver such bold statements—as he did on June 12, 1987, in an address at the Brandenburg Gate of the Berlin Wall. In that speech, written by future Hoover fellow Peter Robinson, Reagan issued his historic challenge: “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!” Two years later, the wall came down. Two years after that, the USSR collapsed.

Bringing Down the Wall

At 7:00 p.m. on November 9, 1989, an announcement of the opening of the border crossings from East to West Berlin prompted Berliners to pour into the streets and make their way to the wall in jubilant celebration.

Some of the revelers were equipped with hammers and chisels to begin the demolition of the hated symbol of the Cold War. The two Germanys were officially reunified in October 1990. The dismantling of the wall lasted into 1992.

Demokratie Jetzt! (Democracy now!), by Wolfgang Janisch, 1990. Wolfgang Janisch Papers, Hoover Institution Archives

Demokratie Jetzt! (Democracy now!), by Wolfgang Janisch, 1990. Wolfgang Janisch Papers, Hoover Institution Archives

Fall of the Berlin Wall, 1989. German Pictorial Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Fall of the Berlin Wall, 1989. German Pictorial Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Fragment of the Berlin Wall, concrete, paint, and steel rebar, n.d. German Subject Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Fragment of the Berlin Wall, concrete, paint, and steel rebar, n.d. German Subject Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Czechoslovakia

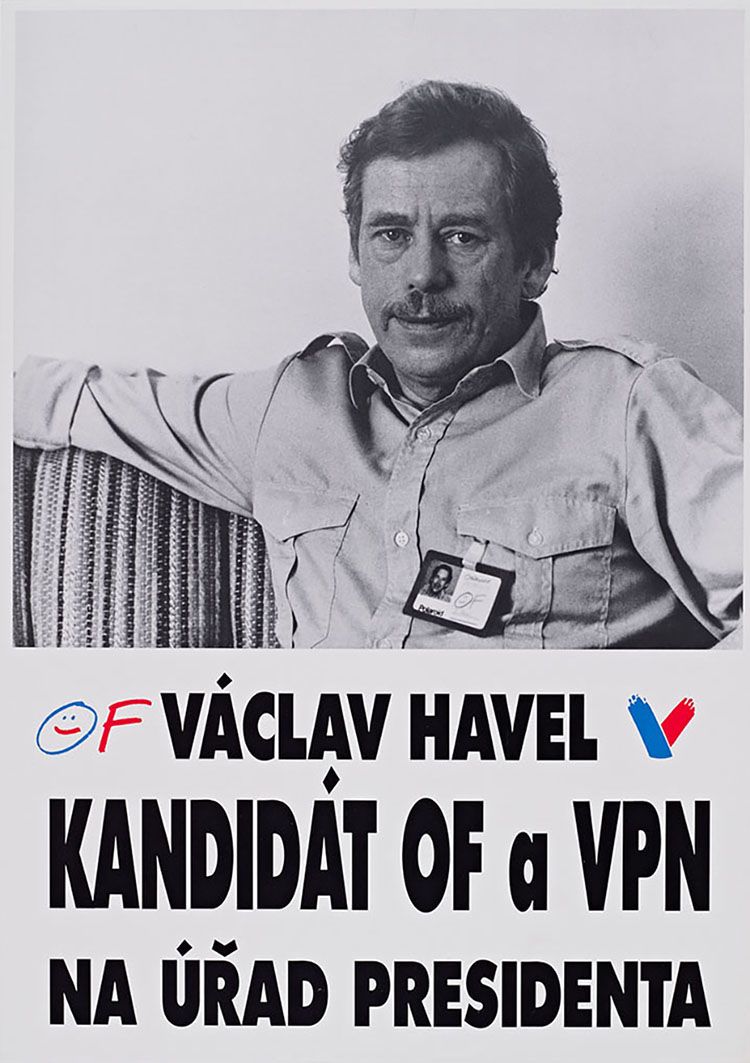

Václav Havel

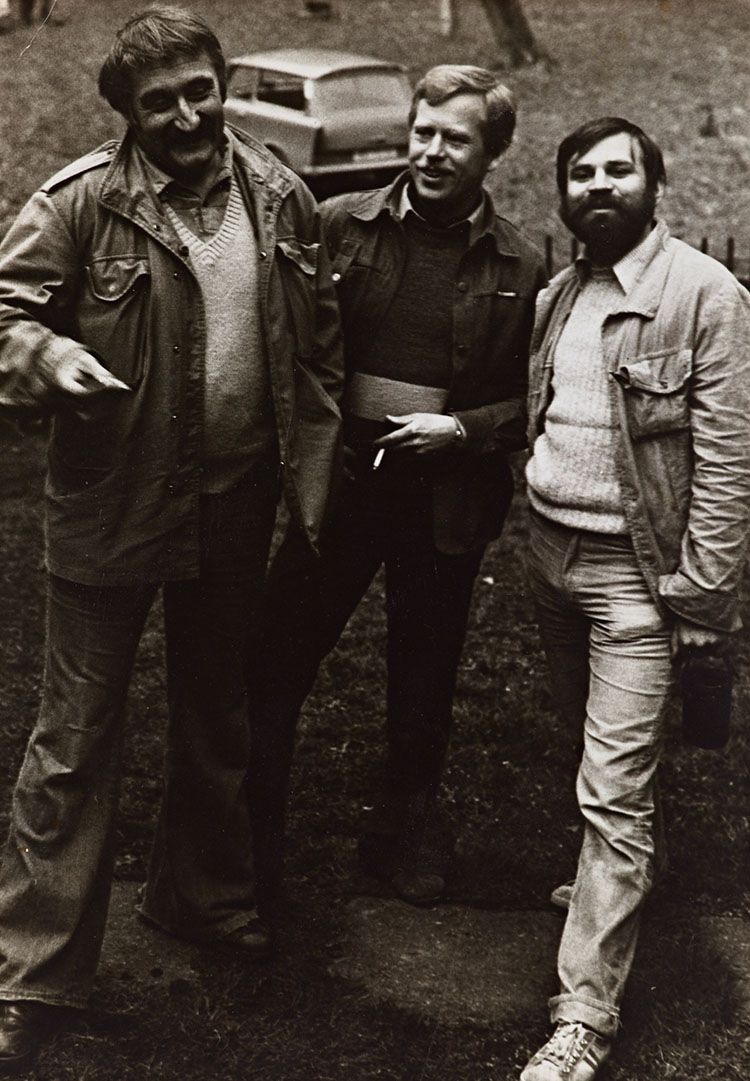

Many dissidents risked their livelihoods, and even their lives, in the fight for freedom against repressive communist regimes. Czech writer Václav Havel is an outstanding example.

A prominent playwright, Havel became an early critic of the communist government in Czechoslovakia and, beginning in the 1960s, was imprisoned several times for his political activism.

Pavel Landovsky, Václav Havel, and Janoslav Kukal, 1978. Petruška Šustrová Papers, Hoover Institution Archives

Pavel Landovsky, Václav Havel, and Janoslav Kukal, 1978. Petruška Šustrová Papers, Hoover Institution Archives

The Prague Trial

In 1979, Václav Havel and five other Czech dissidents were convicted of subversion during a trial in Prague. Havel spent more than four years in prison before being released on February 7, 1983.

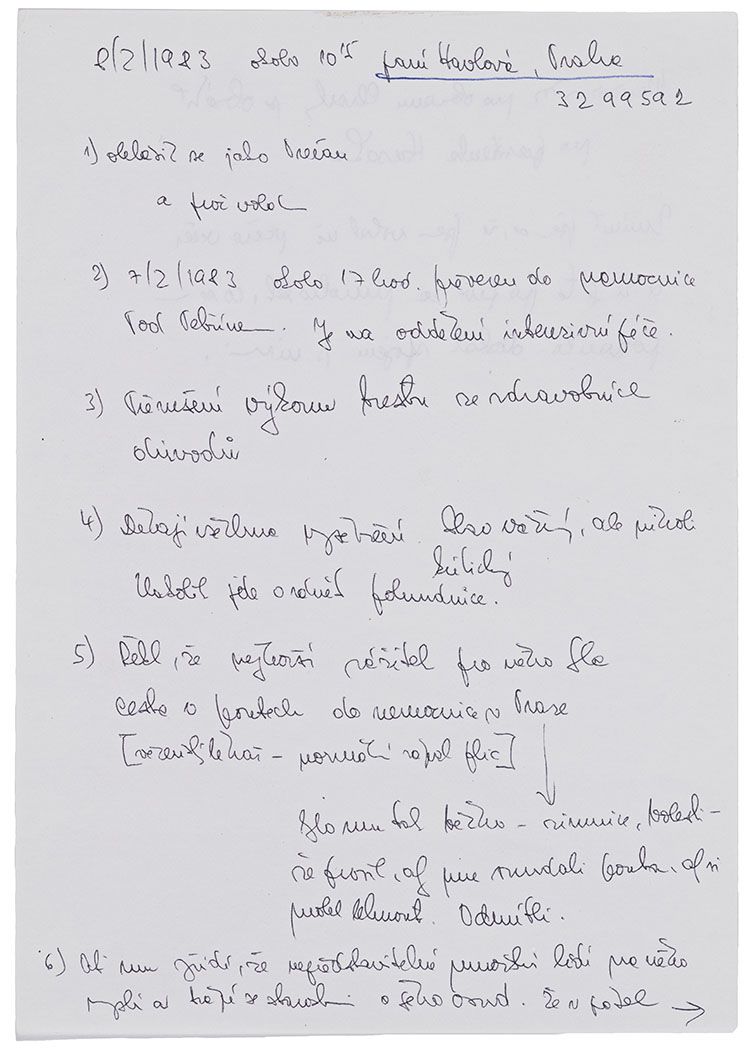

These notes describing Havel’s mistreatment while in custody were taken by Czech historian Vilém Prečan, while on the phone with Havel’s wife, Olga Havlová, the day after Havel left prison.

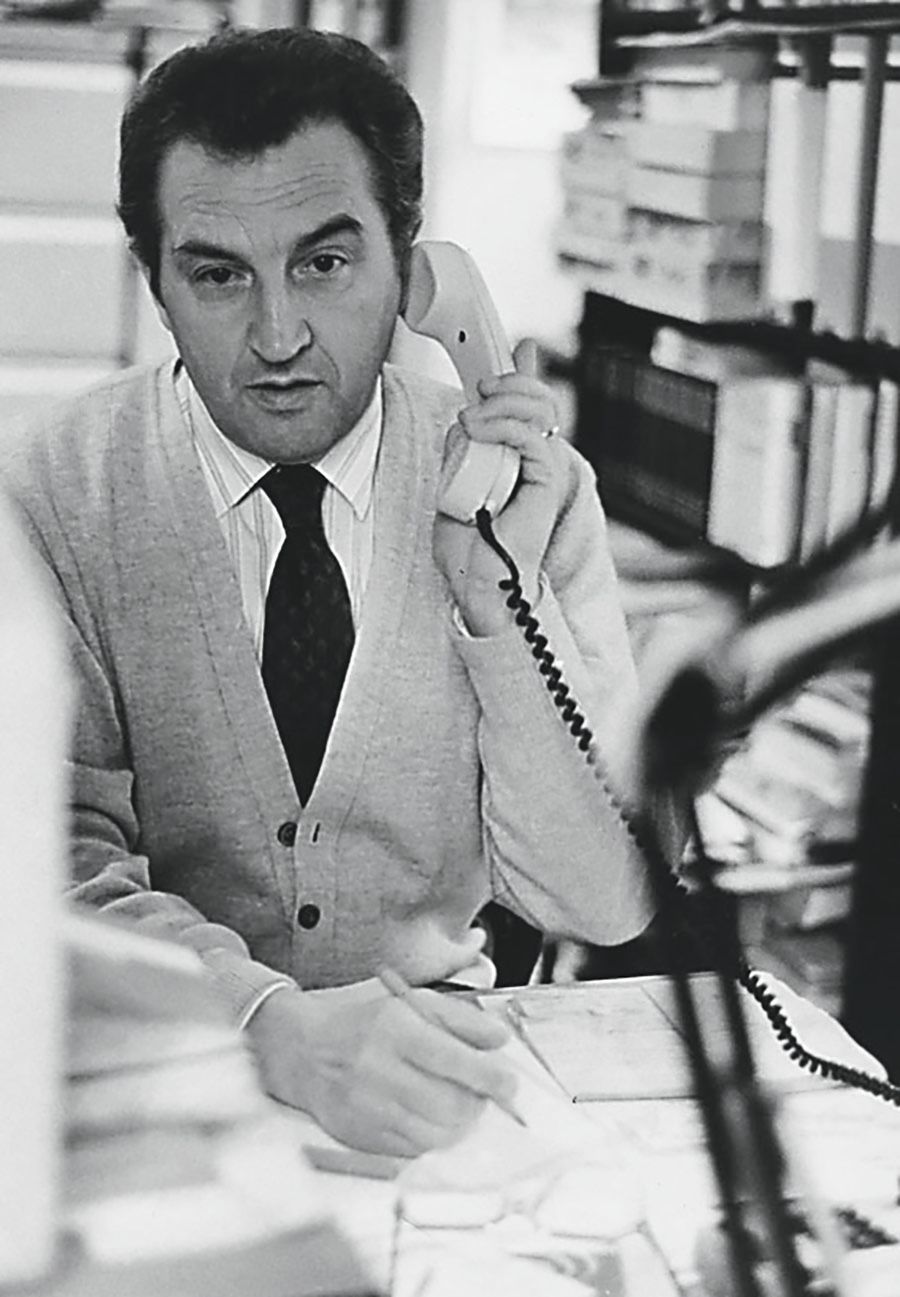

Vilém Prečan calling Václav Havel, 1988. Vilém Prečan Papers, Hoover Institution Archives

Vilém Prečan calling Václav Havel, 1988. Vilém Prečan Papers, Hoover Institution Archives

Notes about Václav Havel’s release from prison, by Vilém Prečan, February 8, 1983. Vilém Prečan Papers, Hoover Institution Archives

Notes about Václav Havel’s release from prison, by Vilém Prečan, February 8, 1983. Vilém Prečan Papers, Hoover Institution Archives

Jiří Wolf

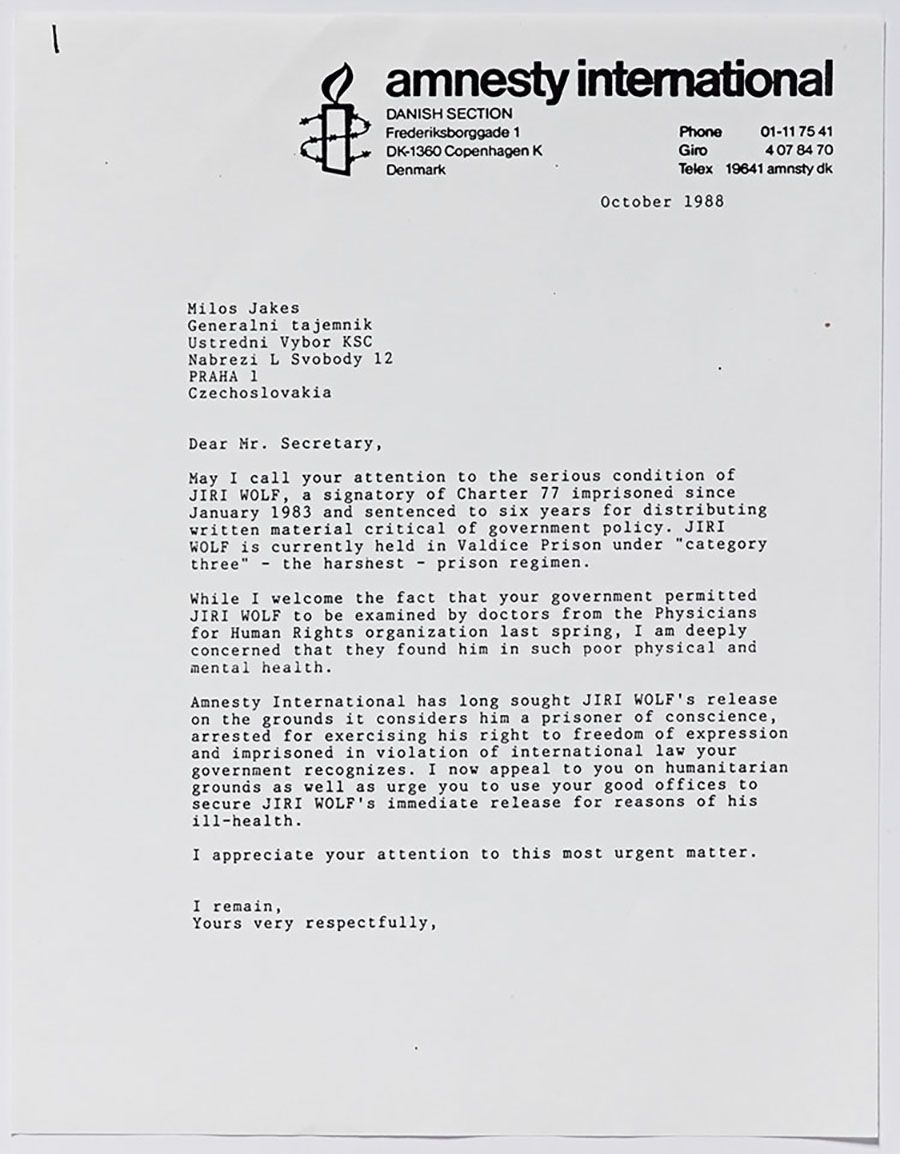

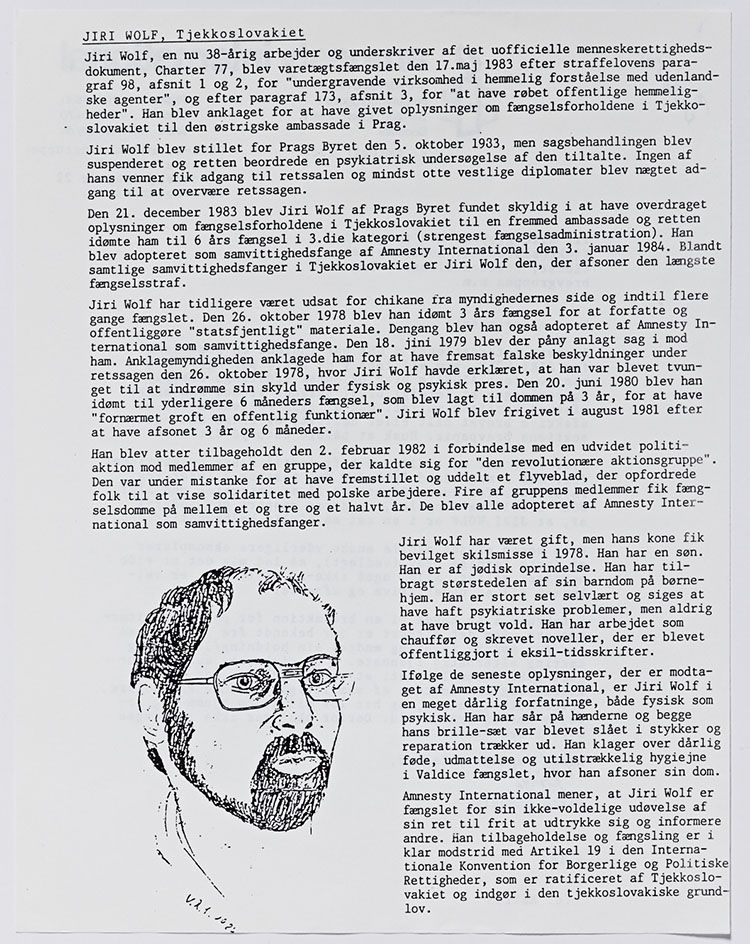

Czech dissident Jiří Wolf was one of many citizens arrested for anti-communist activities in Czechoslovakia. His arrest caught the attention of Amnesty International, a non-governmental human rights organization, which championed his cause. Wolf was eventually released from prison on the same day as Václav Havel.

Amnesty International request for the release of Jiří Wolf, October 1988. Ginetta Sagan Papers, Hoover Institution Archives

Amnesty International request for the release of Jiří Wolf, October 1988. Ginetta Sagan Papers, Hoover Institution Archives

Jiří Wolf, Tjekkoslovakiet (Jiří Wolf, Czechoslovakia), 1988. Ginetta Sagan Papers, Hoover Institution Archives

Jiří Wolf, Tjekkoslovakiet (Jiří Wolf, Czechoslovakia), 1988. Ginetta Sagan Papers, Hoover Institution Archives

The End of Communism in Czechoslovakia

Václav Havel was a leading figure in the country’s 1989 Velvet Revolution, so named because of the peaceful nature of the country's political transition from an authoritarian regime to a parliamentary democracy.

Havel became president of Czechoslovakia in December 1989. When the country split in two in 1992, he became president of the Czech Republic, a position he held until 2003.

Václav Havel, Kandidát OF a VPN, Na Úřad Presidenta (Václav Havel, OF & VPN candidate for president’s office), 1989. Irena Lasota Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Václav Havel, Kandidát OF a VPN, Na Úřad Presidenta (Václav Havel, OF & VPN candidate for president’s office), 1989. Irena Lasota Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Václav Havel presidential campaign pins, 1989. Irena Lasota Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Václav Havel presidential campaign pins, 1989. Irena Lasota Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

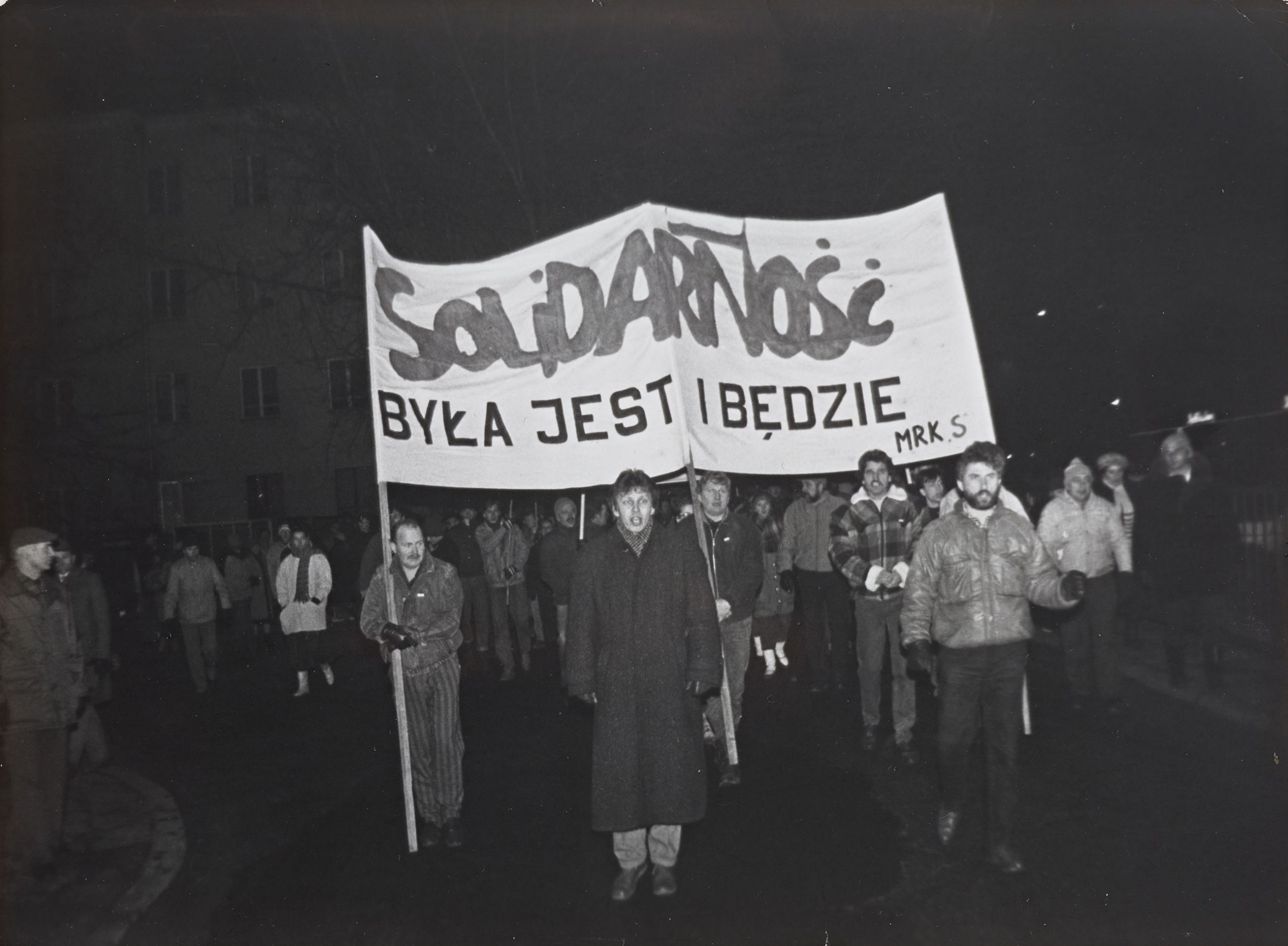

Poland

Solidarity Movement

Solidarity (Solidarność) was a Polish labor union formed in the Lenin Shipyard in the city of Gdansk in 1980. One of Solidarity’s co-founders, an electrician named Lech Wałęsa, became the union's first leader.

Solidarity quickly grew into a nationwide non-violent, anti-Communist resistance movement. In December 1981, Solidarity was outlawed and Wałęsa was arrested as the Polish government introduced martial law and began a brutal crackdown.

Deaths of Polish citizens who died either while detained... or found dead after having been in “official” custody [names redacted], n.d. Ginetta Sagan Papers, Hoover Institution Archives

Deaths of Polish citizens who died either while detained... or found dead after having been in “official” custody [names redacted], n.d. Ginetta Sagan Papers, Hoover Institution Archives

The organization survived underground and, as Communist rule began to falter in the late 1980s, it emerged as Poland’s largest political party.

Solidarity Demonstration, Kraków, Poland, May 1989. European Pictorial Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Solidarity Demonstration, Kraków, Poland, May 1989. European Pictorial Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

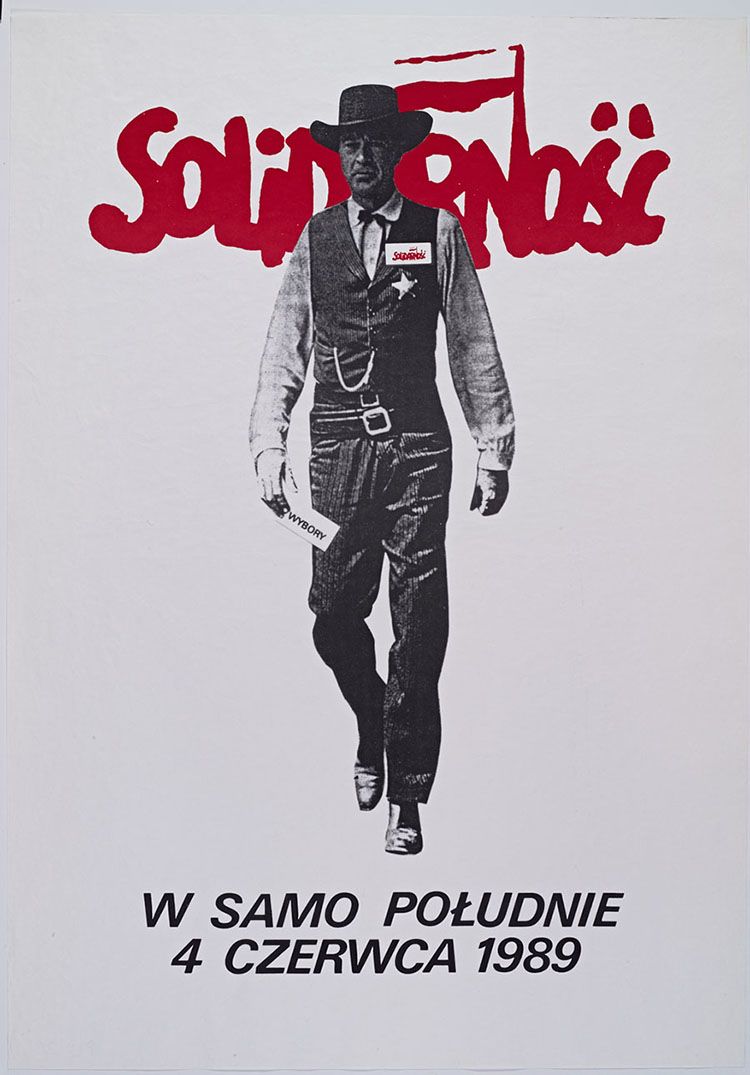

Solidarność, W Samo Południe, 4 Czerwca 1989 (Solidarity, High Noon June 4, 1989), 1989. Poster Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Solidarność, W Samo Południe, 4 Czerwca 1989 (Solidarity, High Noon June 4, 1989), 1989. Poster Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Solidarity Poster

In the Polish national elections of June 4, 1989, Solidarity, the non-governmental trade union–turned–political party, won 99 percent of the freely elected seats in the Polish parliament.

This campaign poster employed an iconic image from American pop culture—Gary Cooper as the sheriff in the classic film High Noon—to convey a sense of gravity of the moment. Here Cooper's sheriff wears a Solidarity logo above his badge and carries a voting ballot where his holstered gun would normally appear.

Poland’s revolution was to be non-violent; the call was to the ballot box, not the barricades.

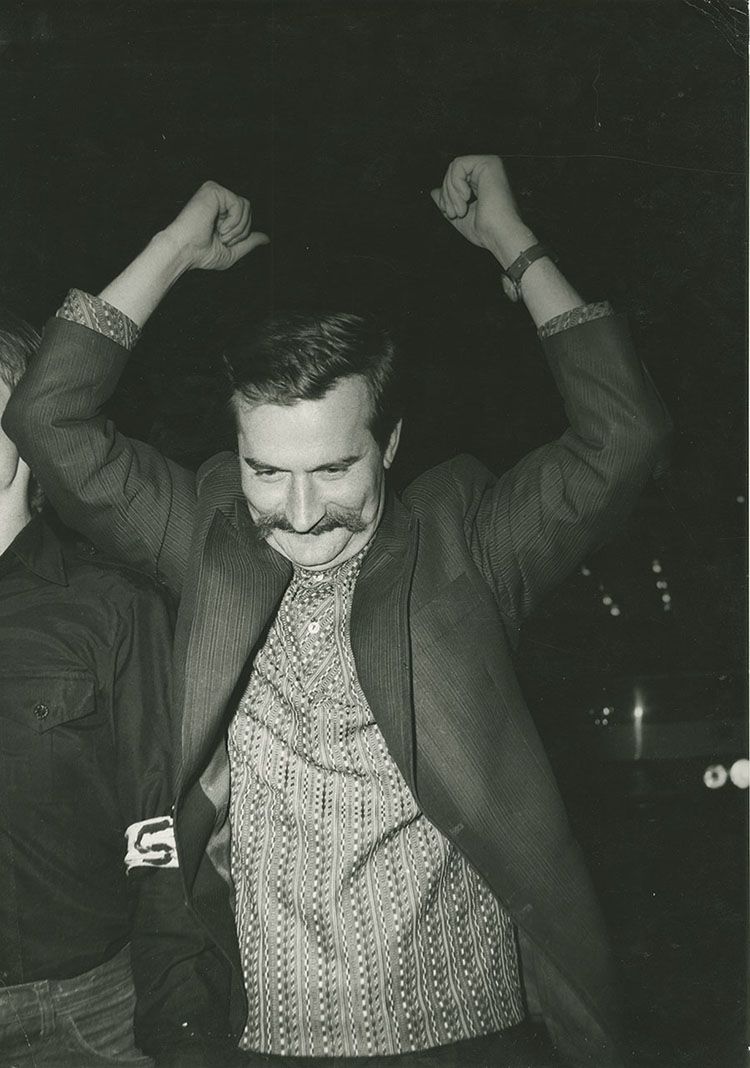

Lech Wałęsa

In the national elections of June 1989, Solidarity won a resounding victory and led Poland’s first post-Communist government. The following year, Wałęsa was elected president of Poland, the first non-Communist head of state in forty-five years.

Lech Wałęsa at the Gdańsk shipyard strike, 1980. Peter K. Raina Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Lech Wałęsa at the Gdańsk shipyard strike, 1980. Peter K. Raina Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

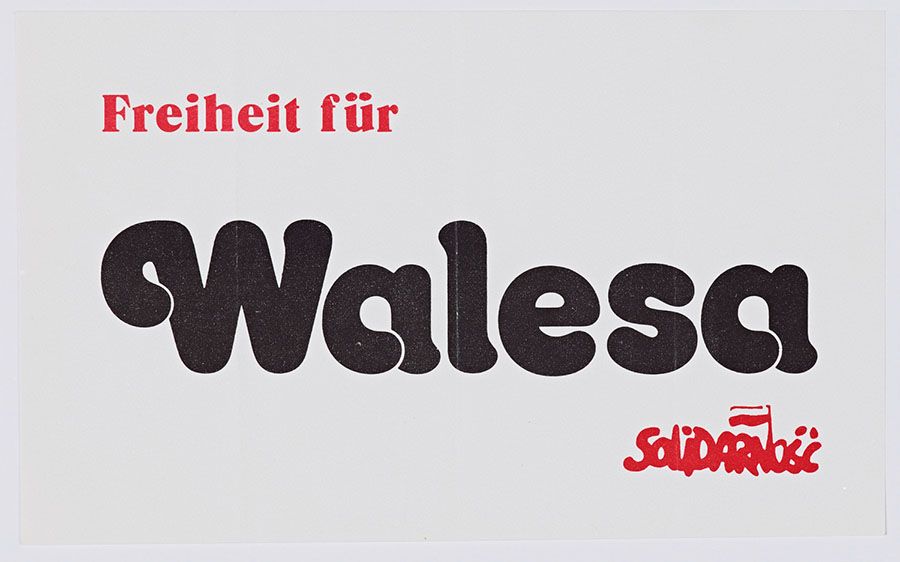

Freiheit für Walesa (Freedom for Walesa), n.d. Peace Subject Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Freiheit für Walesa (Freedom for Walesa), n.d. Peace Subject Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

China

Tiananmen Square

The year 1989 was a seminal one for China, although with starkly different results from those witnessed in Eastern Europe.

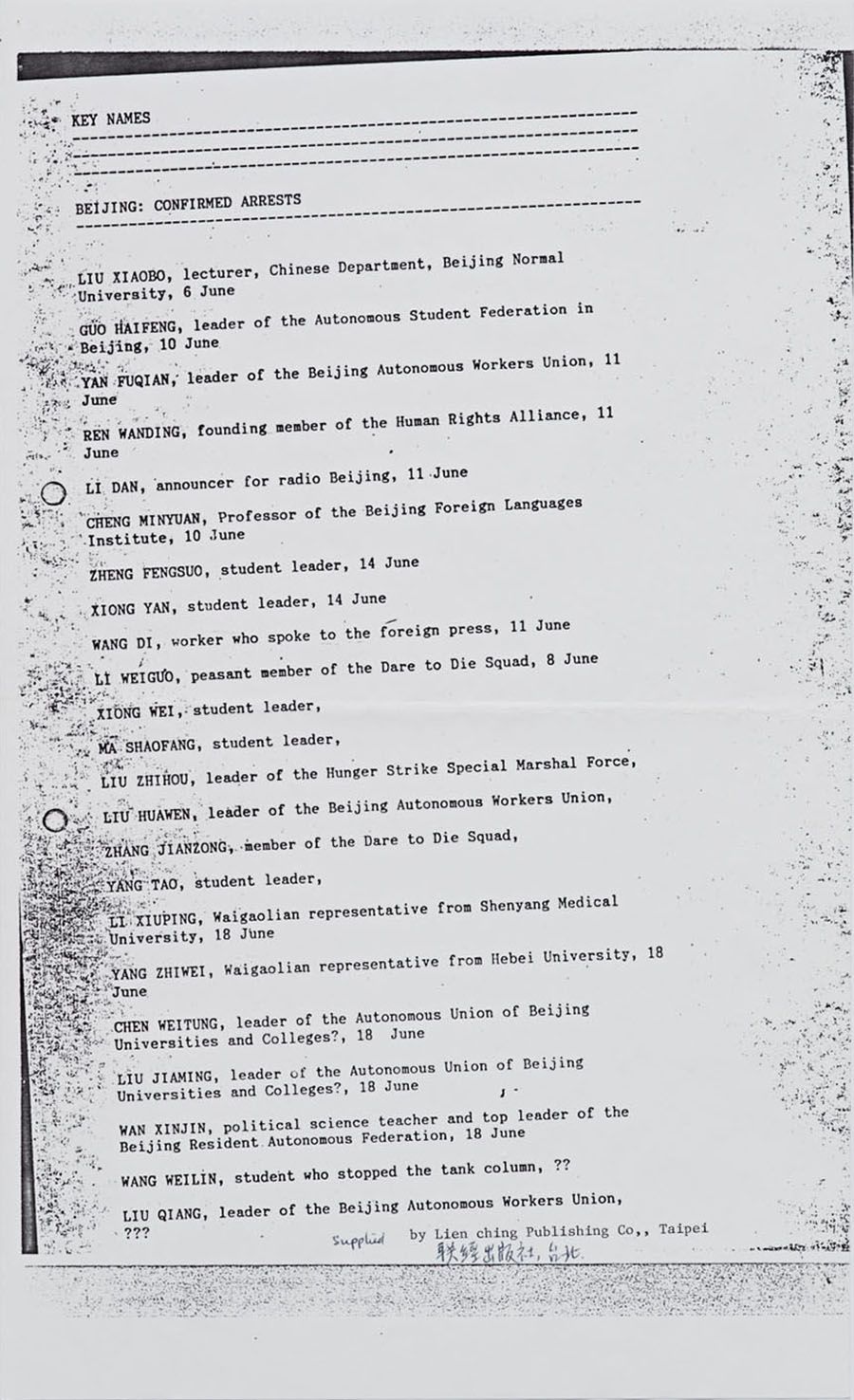

In June of that year, student-led protests in Tiananmen Square in Beijing were brutally suppressed when the government declared martial law and sent in units of the People’s Liberation Army to disperse the crowd. Using tanks and assault rifles, the soldiers fired on the demonstrators. The estimated death toll of the massacre varies from several hundred to thousands.

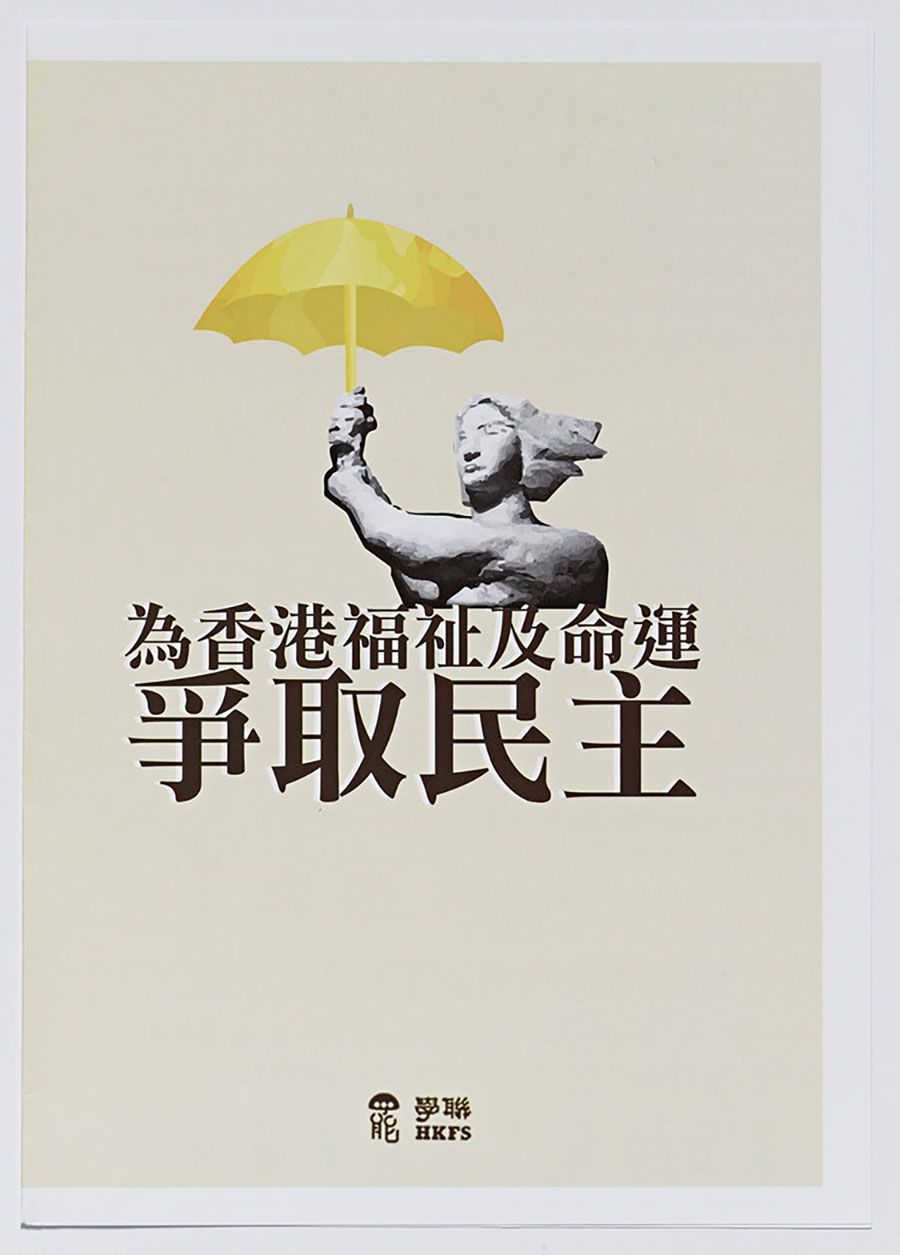

The most potent symbol of the Tiananmen Square protests was the Goddess of Democracy, a massive statue erected in the square by the students and later destroyed by the soldiers. Replicas of the Goddess of Democracy have been put up around the world in homage to the Tiananmen protesters, and images of the statue are still used as representations of the desire for freedom and democracy in China.

Tiananmen Square, China, June 1, 1989. Julia Tung Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Tiananmen Square, China, June 1, 1989. Julia Tung Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Tiananmen Square, China, June 4, 1989. Julia Tung Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Tiananmen Square, China, June 4, 1989. Julia Tung Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Key Names, Beijing: Confirmed Arrests, 1989. Julia Tung Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Key Names, Beijing: Confirmed Arrests, 1989. Julia Tung Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Goddess of Democracy postcard, 1989. Julia Tung Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Goddess of Democracy postcard, 1989. Julia Tung Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Goddess of Democracy, earthenware, n.d. Lesley A. Rimmel Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Goddess of Democracy, earthenware, n.d. Lesley A. Rimmel Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

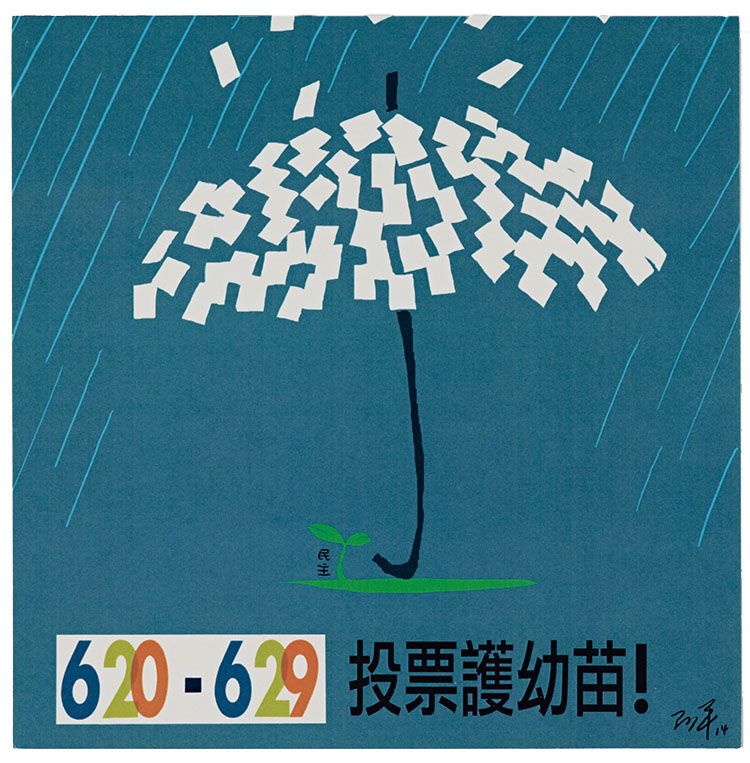

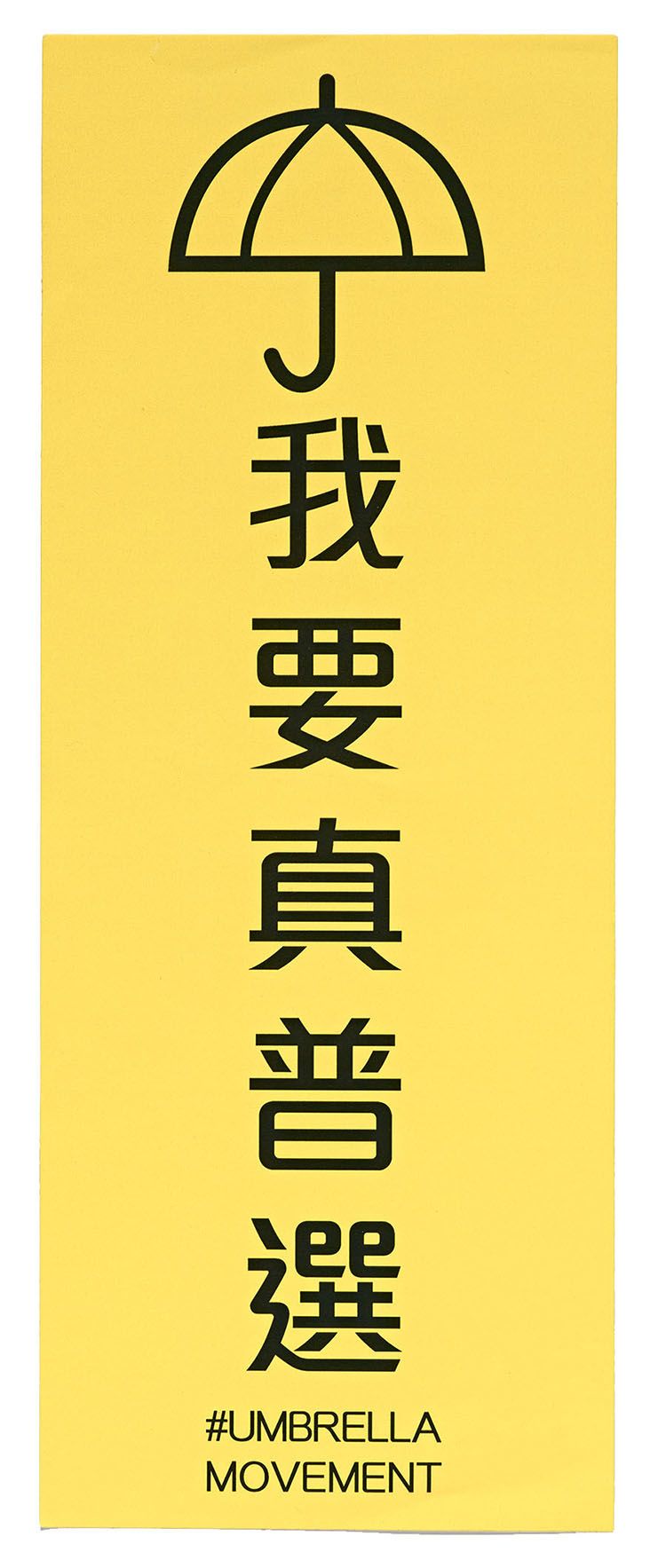

Umbrella Movement

Another symbol of freedom in China emerged in 2014 when thousands of people in Hong Kong joined the so-called Umbrella Movement, a series of large-scale sit-in protests involving tens of thousands of people over the course of seventy-nine days. The participants objected to the Beijing government’s attempt to limit free elections and to constrain democracy in other ways in Hong Kong.

Printed leaflets and pamphlets designed by protesters show the umbrella symbolically protecting the seedling of democracy, although in real life the activists’ umbrellas also served a practical purpose: they were used to ward off the pepper spray used by the police to disperse the protesters.

The activists also used the imagery of the Goddess of Democracy, directly referencing the events that occurred twenty-five years earlier.

I Want a General Election, 2014. Hong Kong Umbrella Revolution Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

I Want a General Election, 2014. Hong Kong Umbrella Revolution Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Vote to Protect the Seedling!, 2014. Hong Kong Umbrella Revolution Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Vote to Protect the Seedling!, 2014. Hong Kong Umbrella Revolution Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Umbrella Revolution, 2014. Hong Kong Umbrella Revolution Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Umbrella Revolution, 2014. Hong Kong Umbrella Revolution Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

I Want a General Election leaflet, 2014. Hong Kong Umbrella Revolution Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

I Want a General Election leaflet, 2014. Hong Kong Umbrella Revolution Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

The Hoover Institution Library & Archives wishes to receive notifications of alleged copyright infringement on this website. If you are a rights holder and believe that our inclusion of certain material on this website violates your rights, please contact: https://www.hoover.org/library-archives/collections/get-help/rights-and-permissions

© 2022 by the Board of Trustees of Leland Stanford Junior University.

![Deaths of Polish citizens who died either while detained... or found dead after having been in “official” custody [names redacted], no date. From the Ginetta Sagan Papers, Hoover Institution Archives.](./assets/voKXUIagxb/83017_20-for-web-cropped-redacted-72-900x1164.jpeg)