Give Bread + Medicine

Maxim Gorky's Appeals

The Great Famine of 1921 in Soviet Russia claimed more than six million lives, making it the most catastrophic European famine in modern history. The Soviet government under Vladimir Lenin had for months been aware of signs of the impending disaster, but it was not until the summer of 1921 that the leadership at last seemed to recognize the enormity of the danger and began to act—though it took longer still to arrive at the decision to request outside assistance. Having to seek food relief from abroad would have been embarrassing for any government, but for the pariah government in the Kremlin the prospect was supremely humiliating.

The first official acknowledgment of the crisis appeared in Pravda on June 26, which described a famine worse than that of 1891, affecting about twenty-five million people, a total later raised to thirty-five million. Subsequently, on June 30, Pravda reported that a mass flight from the famine regions was underway. Such articles multiplied in July when they were picked up by the European press; American awareness of the catastrophe came more slowly.1

Initially, Bolshevik publicists openly scorned the idea of applying to Western governments for aid and claimed to be counting on the contributions of the international proletariat. But the leadership understood that any significant relief from abroad would have to be sponsored by imperialist governments. In the first week of July, two appeals went out from Moscow, one from Patriarch Tikhon of the Russian Orthodox Church and the other, of far greater consequence, from Maxim Gorky.

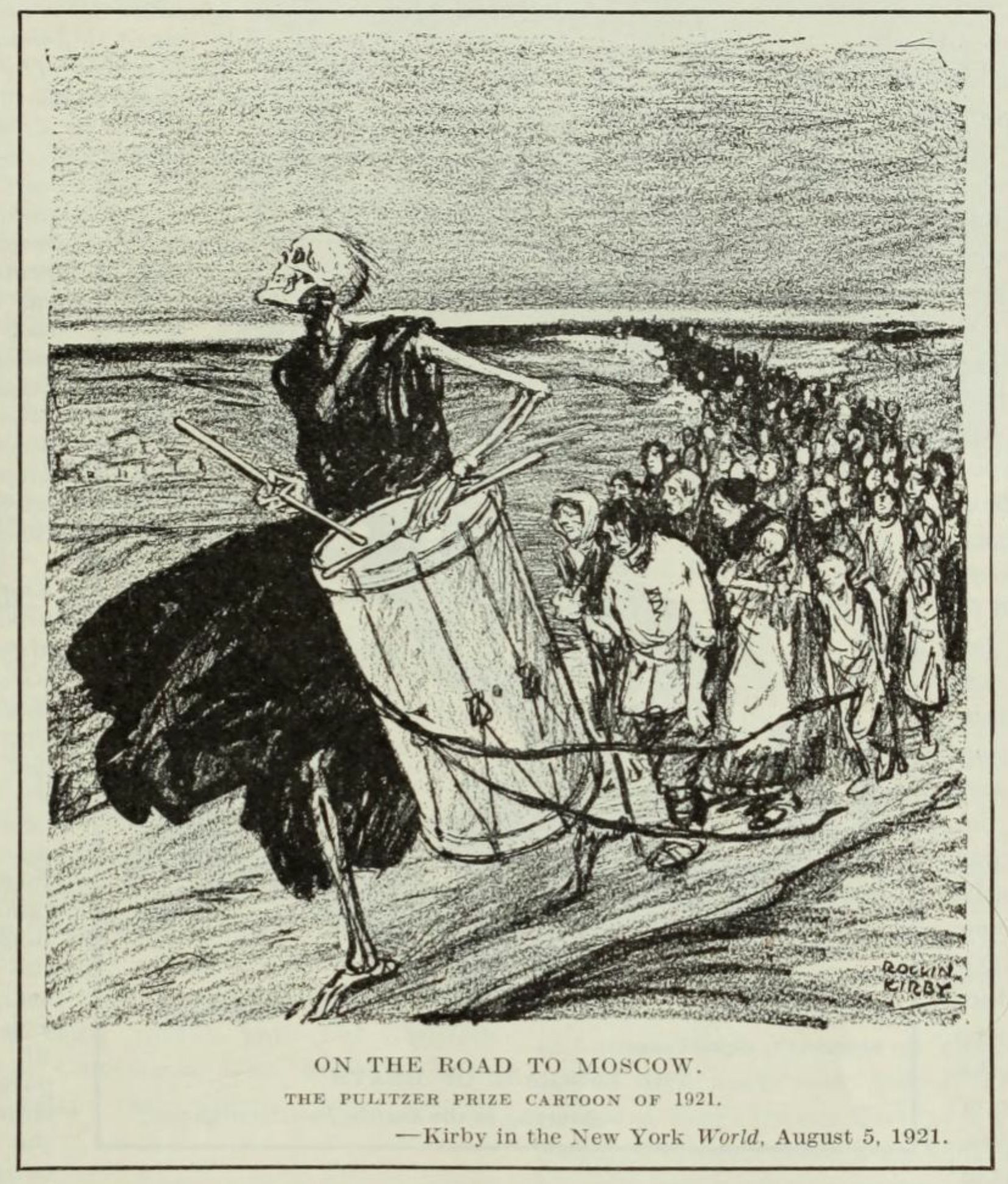

"On the Road to Moscow" by Rollin Kirby, originally published in New York World, August 5, 1921. This copy is from Literary Digest, June 10, 1922. Kirby received the inaugural Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning in 1922 for this cartoon.

"On the Road to Moscow" by Rollin Kirby, originally published in New York World, August 5, 1921. This copy is from Literary Digest, June 10, 1922. Kirby received the inaugural Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning in 1922 for this cartoon.

Vladimir Lenin in Red Square, circa 1919.

Hugh Anderson Moran papers (48025), Hoover Institution Archives.

Patriarch Tikhon of Moscow, circa 1920.

Wikimedia Commons.

Maxim Gorky carte de visite by Mishkin, NY, 1906.

Boris I. Nicolaevsky Collection (63013), Hoover Institution Archives.

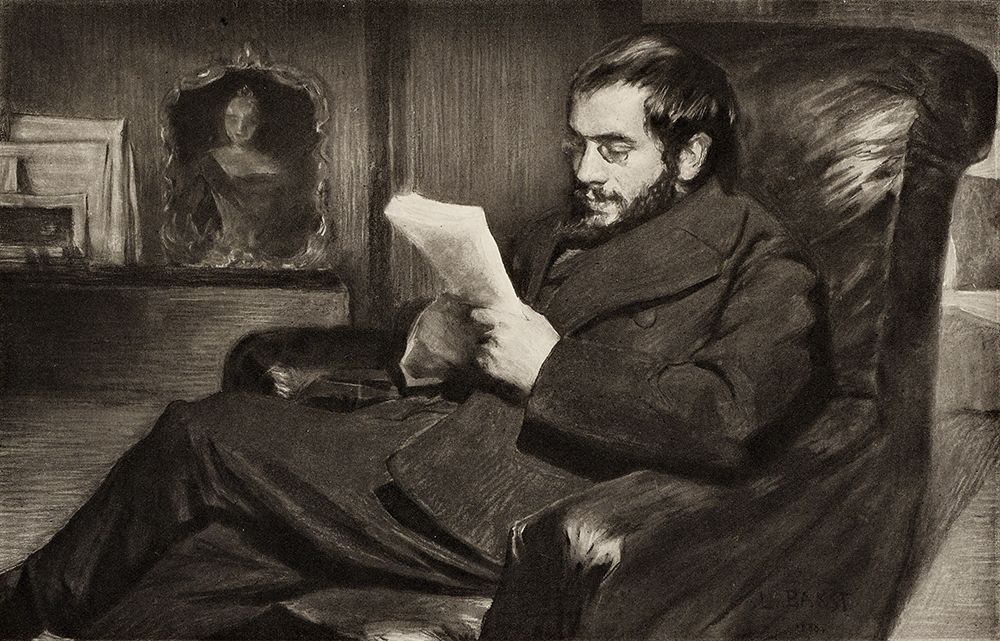

Gorky was a world-renowned writer whose fiction probed conditions among the lower classes of society and who was nominated five times for the Nobel Prize in Literature. He was also active in the revolutionary movement and for a period was a close comrade of Vladimir Lenin’s. The two men had a long and complicated relationship. Since the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, Gorky had been serving as a kind of intercessor for the intelligentsia with the government, a role facilitated by his personal access to the Soviet leader. This involved him in situations of political and moral ambiguity sufficient to earn him detractors and enemies among anti-Bolsheviks. His ambiguous political status suited him to the job of petitioning the outside world on behalf of Soviet Russia.2

Gorky’s appeal, “To All Honest People,” was published in the West in mid-July 1921. In typically dry prose its author announced that a crop failure caused by drought was threatening the lives of millions of Russians. He invoked the common cultural heritage of Europeans and Americans. “Gloomy days have come to the country of Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Mendeleyev, Pavlov, Mussorgsky, Glinka, and other world-prized men.” In other words, forget for the moment the names of Lenin and Trotsky: “I ask all honest European and American people for prompt aid to the Russian people. Give bread and medicine.”

Gorky at Petrograd Railway Station, bound for Moscow, 1920. Courtesy A. M. Gorky Museum, Moscow

Gorky’s appeal as printed in the New York Times, July 31, 1921.

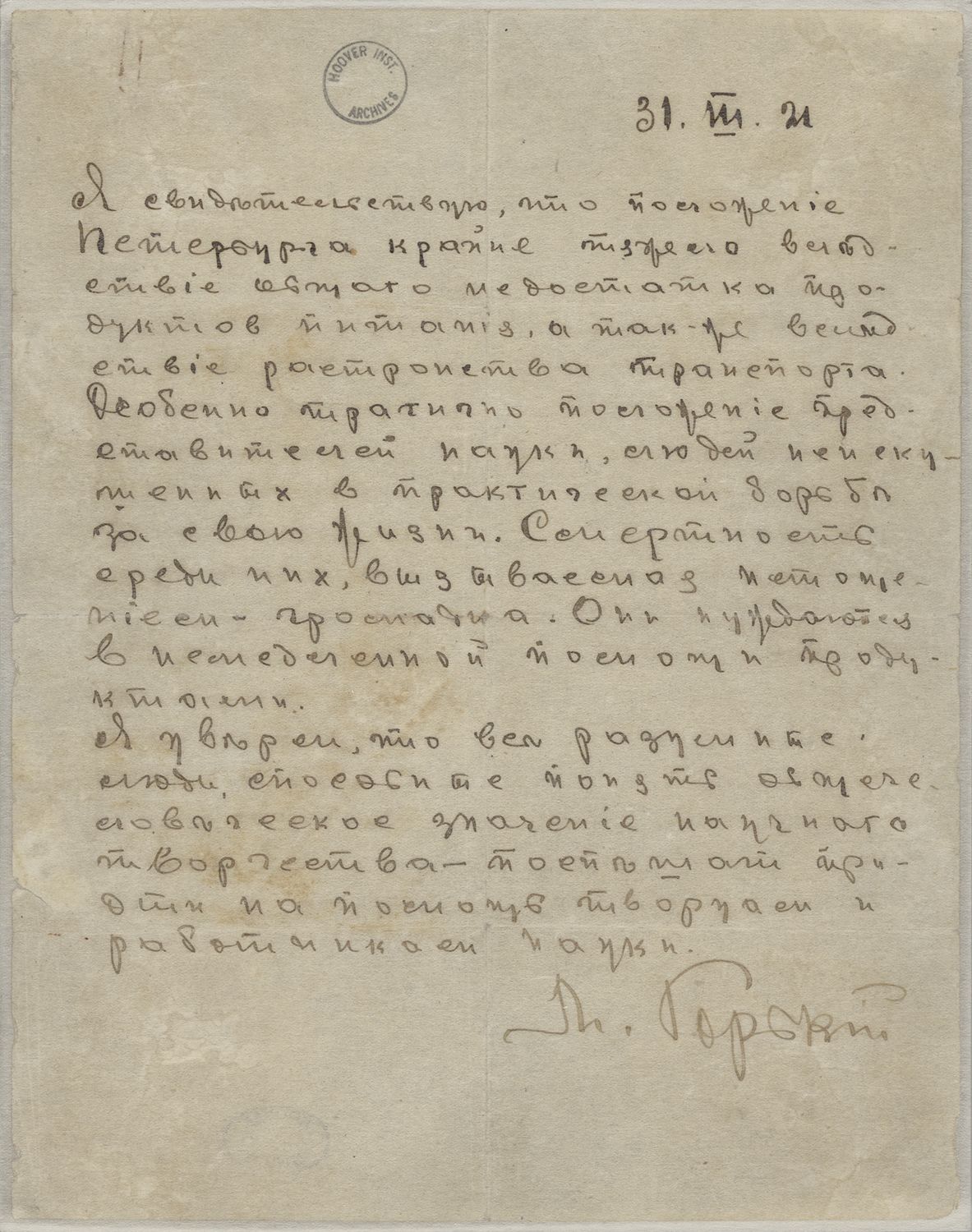

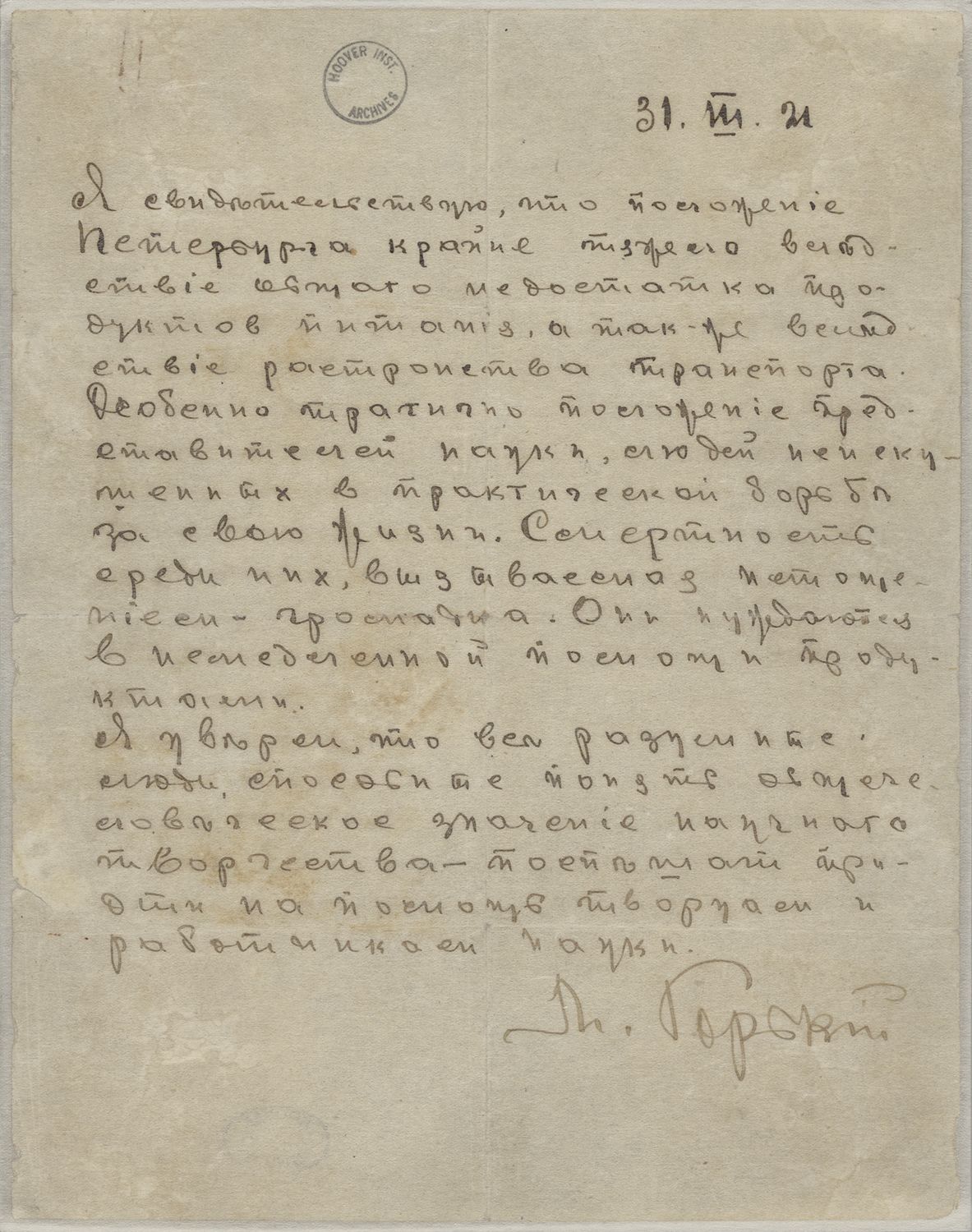

Maxim Gorky's appeal to Henri Barbusse, March 31, 1921. Hoover Institution Archives (63003).

Maxim Gorky's appeal to Henri Barbusse, March 31, 1921. Hoover Institution Archives (63003).

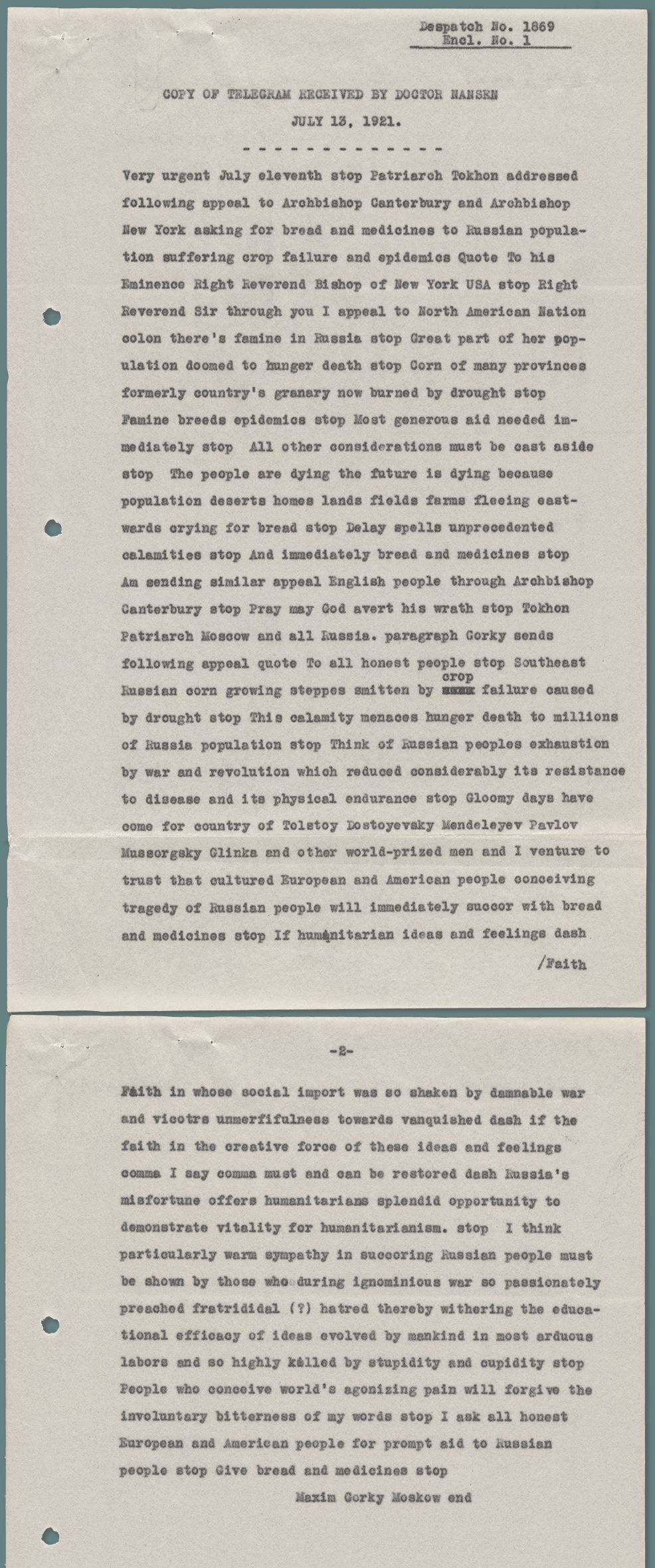

Gorky’s appeal, as well as the one he solicited from Patriarch Tikhon, were written on or near July 6 and sent together in the same telegram to Norwegian explorer-turned-humanitarian Fridtjof Nansen in Norway, who received them on July 13. Tikhon’s appeal was directed both to the British people, through the archbishop of Canterbury, and to the American people, through the archbishop of New York. Nansen seems to have relayed Tikhon’s message to the intended recipients, and it found its way into the American press prior to July 21, according to the New York Times, which published the full text on July 31.5

On July 14 Nansen replied by wire to Gorky that only the Americans could provide substantial assistance and that he had better concentrate his efforts on that audience. At the same time, Nansen passed Gorky's appeal on to the American minister in Norway, who forwarded it to the State Department, where it would arrive on July 29—only after it had been reported on in the United States.6

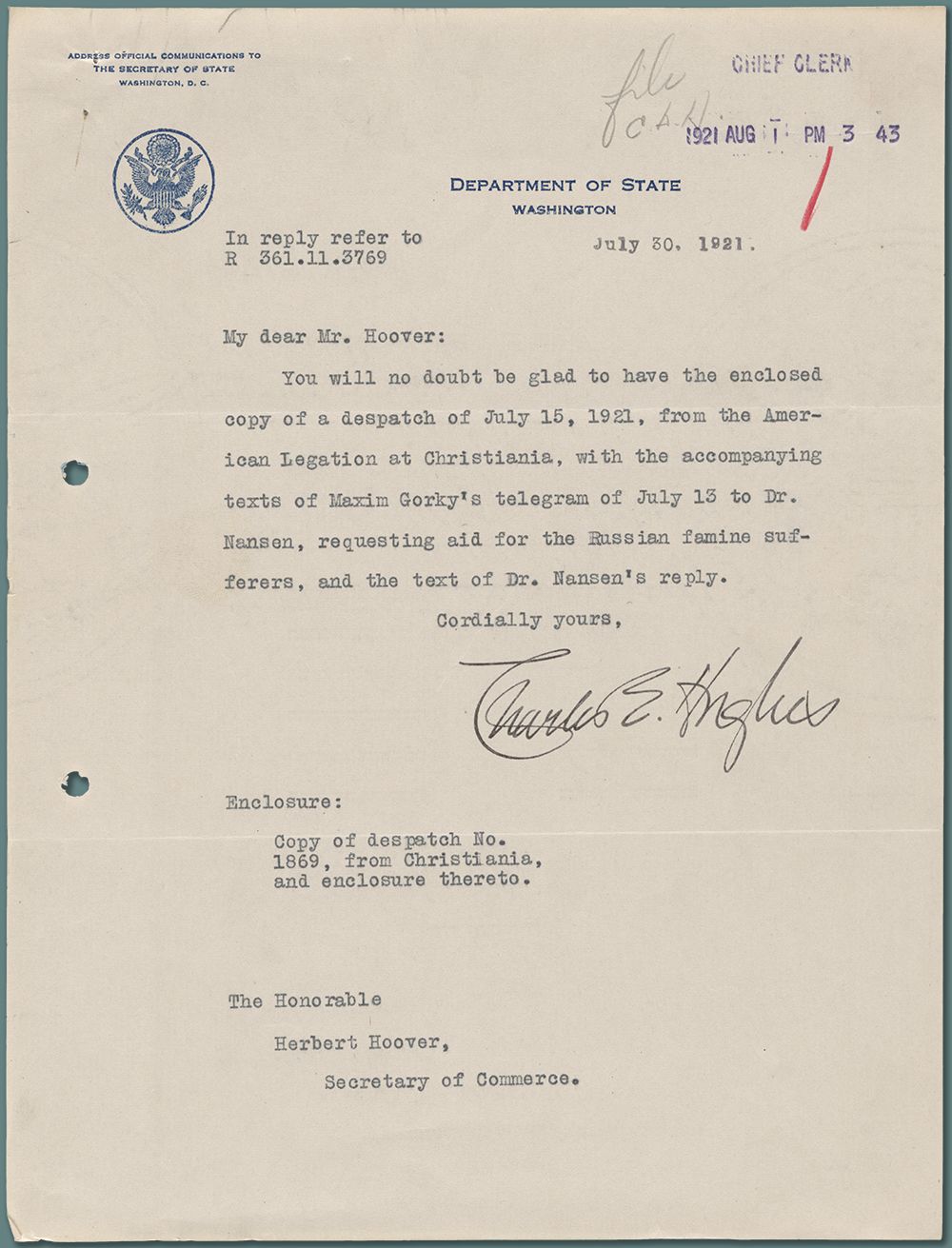

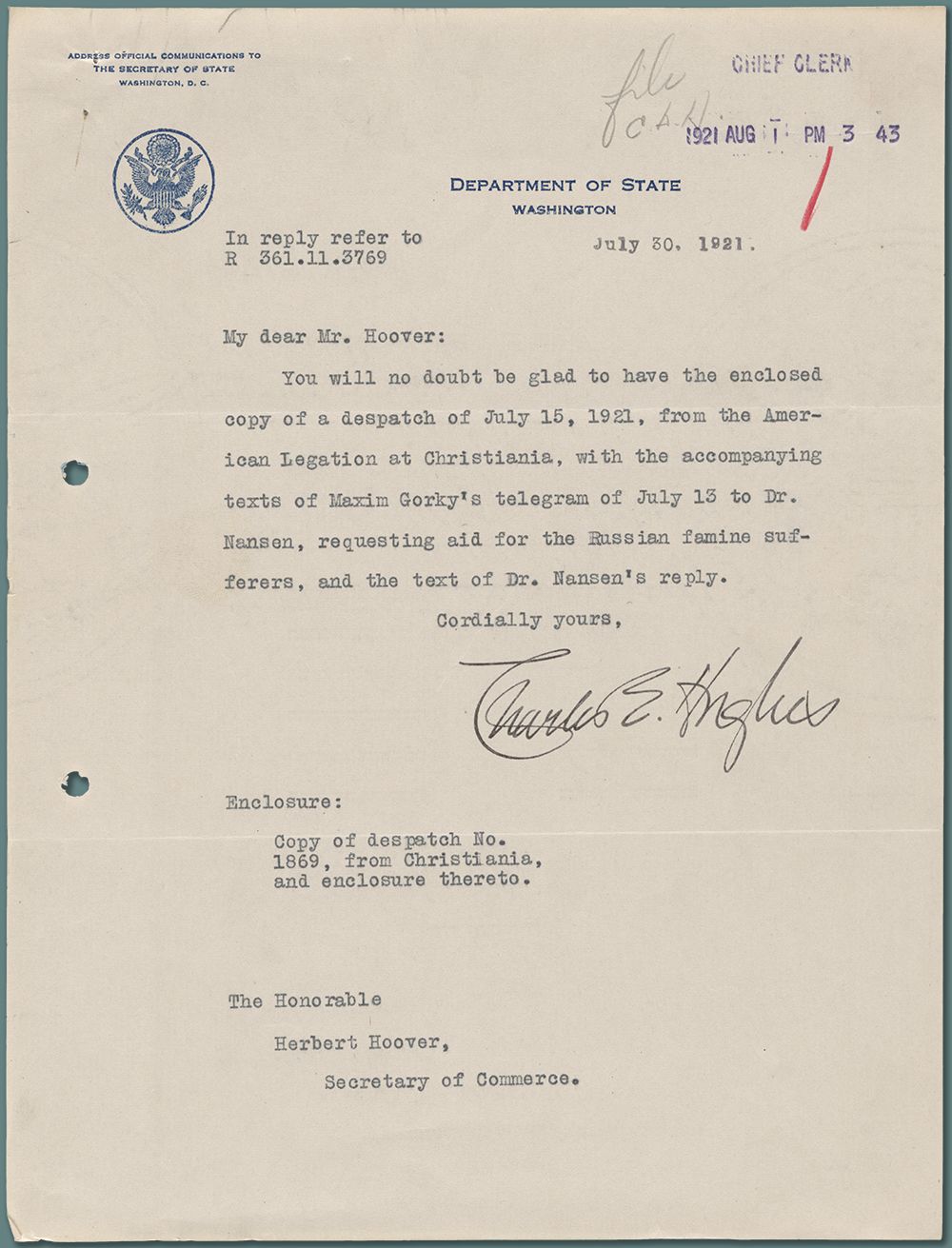

Cover Letter to Herbert Hoover from US Secretary of State Charles Hughes, July 30, 1921. ARA Russia, box 317, folder 13.

Cover Letter to Herbert Hoover from US Secretary of State Charles Hughes, July 30, 1921. ARA Russia, box 317, folder 13.

This appeal called for aid for a broad swath of the Russian population. Until then, Gorky's focus had been on intellectuals in the capital cities, Petrograd and Moscow, where hunger reigned well before the outbreak of the famine of 1921. In March 1921 Gorky wrote out by hand an appeal for aid intended for the French novelist Henri Barbusse in Paris, to be delivered by a Baltic journalist visiting Petrograd.

I testify that the situation in Petersburg3 is extremely difficult because of a general scarcity of food products and the disorganization of transport. Especially tragic is the situation of the representatives of science, people inexperienced in the practical struggle for their life. Mortality among them, brought on by exhaustion, is tremendous. They are in immediate need of food relief.

I am sure that all reasonable people capable of understanding the universal significance of scientific creativity will hasten to come to the aid of the creators and workers of science.4

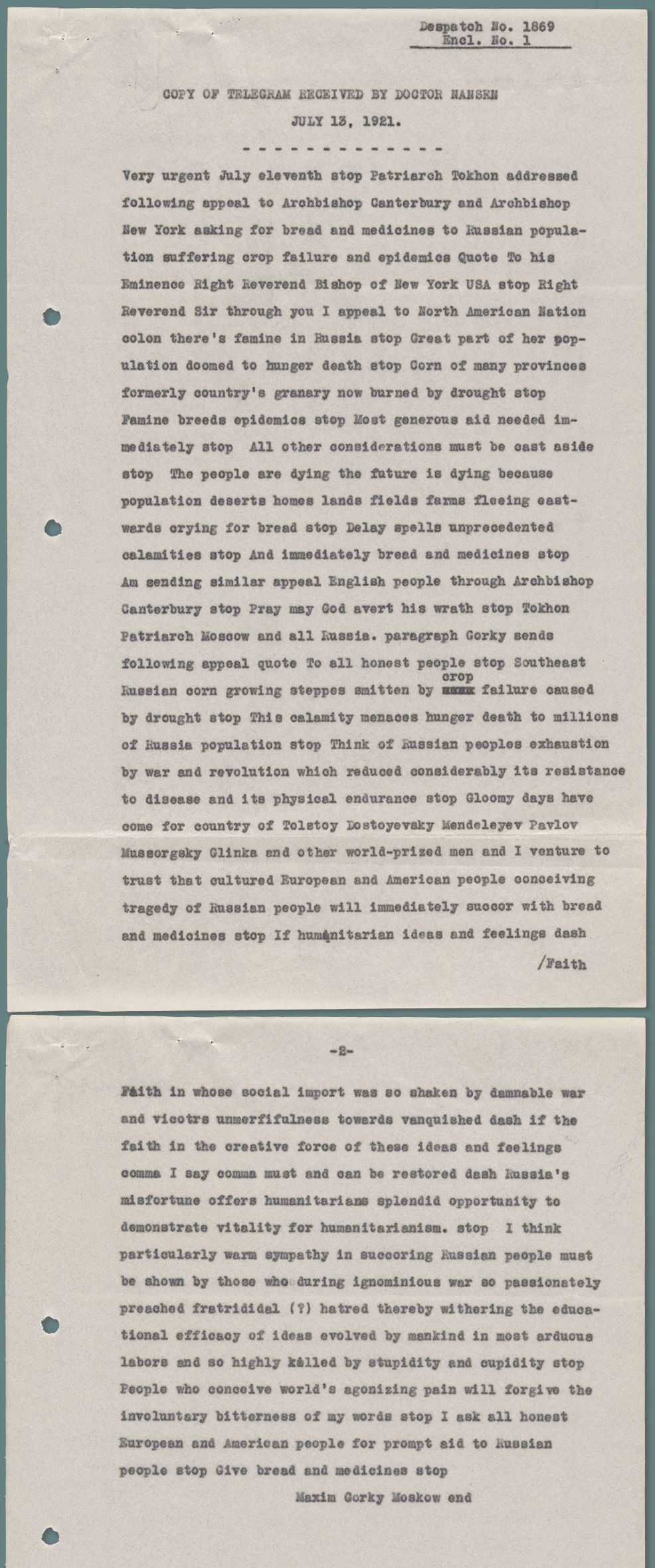

Copy of Gorky's July 13 telegram to Dr. Nansen forwarded to Herbert Hoover from the US State Department, July 30, 1921. ARA Russia, box 317, folder 13.

Copy of Gorky's July 13 telegram to Dr. Nansen forwarded to Herbert Hoover from the US State Department, July 30, 1921. ARA Russia, box 317, folder 13.

This appeal called for aid for a broad swath of the Russian population. Until then, Gorky’s focus had been on intellectuals in the capital cities, Petrograd and Moscow, where hunger reigned well before the outbreak of the famine of 1921. In March 1921 Gorky wrote out by hand an appeal for aid intended for the French novelist Henri Barbusse in Paris, to be delivered by a Baltic journalist visiting Petrograd.

I testify that the situation in Petersburg3 is extremely difficult because of a general scarcity of food products and the disorganization of transport. Especially tragic is the situation of the representatives of science, people inexperienced in the practical struggle for their life. Mortality among them, brought on by exhaustion, is tremendous. They are in immediate need of food relief.

I am sure that all reasonable people capable of understanding the universal significance of scientific creativity will hasten to come to the aid of the creators and workers of science.4

Maxim Gorky's appeal to Henri Barbusse, March 31, 1921. Hoover Institution Archives (63003).

Maxim Gorky's appeal to Henri Barbusse, March 31, 1921. Hoover Institution Archives (63003).

Gorky’s appeal, as well as the one he solicited from Patriarch Tikhon, were written on or near July 6 and sent together in the same telegram to Norwegian explorer-turned-humanitarian Fridtjof Nansen in Norway, who received them on July 13. Tikhon’s appeal was directed both to the British people, through the archbishop of Canterbury, and to the American people, through the archbishop of New York. Nansen seems to have relayed Tikhon’s message to the intended recipients, and it found its way into the American press prior to July 21, according to the New York Times, which published the full text on July 31.5

On July 14 Nansen replied by wire to Gorky that only the Americans could provide substantial assistance and that he had better concentrate his efforts on that audience. At the same time, Nansen passed Gorky's appeal on to the American minister in Norway, who forwarded it to the State Department, where it would arrive on July 29—only after it had been reported on in the United States.6

Cover Letter to Herbert Hoover from US Secretary of State Charles Hughes, July 30, 1921. ARA Russia, box 317, folder 13.

Cover Letter to Herbert Hoover from US Secretary of State Charles Hughes, July 30, 1921. ARA Russia, box 317, folder 13.

Copy of Gorky's July 13 telegram to Dr. Nansen forwarded to Herbert Hoover from the US State Department, July 30, 1921. ARA Russia, box 317, folder 13.

Copy of Gorky's July 13 telegram to Dr. Nansen forwarded to Herbert Hoover from the US State Department, July 30, 1921. ARA Russia, box 317, folder 13.

The Soviet famine became front-page news in the United States, where one now heard the opinion expressed that this might sound the death knell of the Bolshevik experiment at long last—if not the downfall of the Soviet regime, then at least its comeuppance. An article in the New York Times reflected the idea that this moment was a turning point. “The alarmed state of mind of the Bolshevist chieftains is exemplified by the flock of world wide wireless propaganda appeals suffered to be sent from Moscow painting the situation in darkest colors. Apparently no longer is it Bolshevist tactics to bluff, pretending everything is fine.”7

Americans of a certain age would have remembered Gorky’s scandal-ridden 1906 visit to New York. Gorky arrived in New York, to great fanfare, in April 1906, at the invitation of Mark Twain and other American writers. He had recently been freed from a tsarist prison, where he had been incarcerated for his role in the Revolution of 1905, a release won as a result of international protest. For a few days the New York papers gave Gorky’s visit prominent and favorable attention. Then, on April 15, came the bombshell revelation that the woman Gorky was traveling with was in fact not Madame Gorky but a famous actress, Maria Andreyeva. Gorky’s legal wife, from whom he had amicably separated years earlier, was still living in Russia. Suddenly, the famous visitor was no longer made to feel welcome. The tentative invitation to visit President Theodore Roosevelt at the White House was withdrawn. Hotels refused admittance to the couple. On April 19, the San Francisco earthquake knocked the Gorky story off the front pages, but the newspaper coverage remained largely negative until his departure from the United States in October.8

Cropped newspaper article from the New York Times, April 15, 1906, alongside a cropped photograph of Maxim Gorky and Maria Andreyeva at Ilya Repin's dacha, 1905.

Cropped newspaper article from the New York Times, April 15, 1906, alongside a cropped photograph of Maxim Gorky and Maria Andreyeva at Ilya Repin's dacha, 1905.

In 1921, ambivalent feelings about Gorky were evident in the US press coverage of the famine. In an opinion piece published by the New York Times, Dr. J. V. Hessen, a liberal Russian émigré lawyer and publicist, saw it as a moment of reckoning not just for the Soviet regime but for Gorky himself.

The profoundest impression was created by the impassioned appeal of Gorky, who was frightened by the sufferings of the Russian people. Only a year ago, singing the praises of Lenin, this same Gorky said: “I was against the Bolsheviki, but I have convinced myself that the Russian people can suffer better than they can work, and I sing the praise of the madness of the brave.” But it has turned out that the Bolsheviki have succeeded in breaking even the endurance of the Russian people, and that the “madness of the brave” has yielded its results. Gorky is calling upon the world to save the Russian people.9

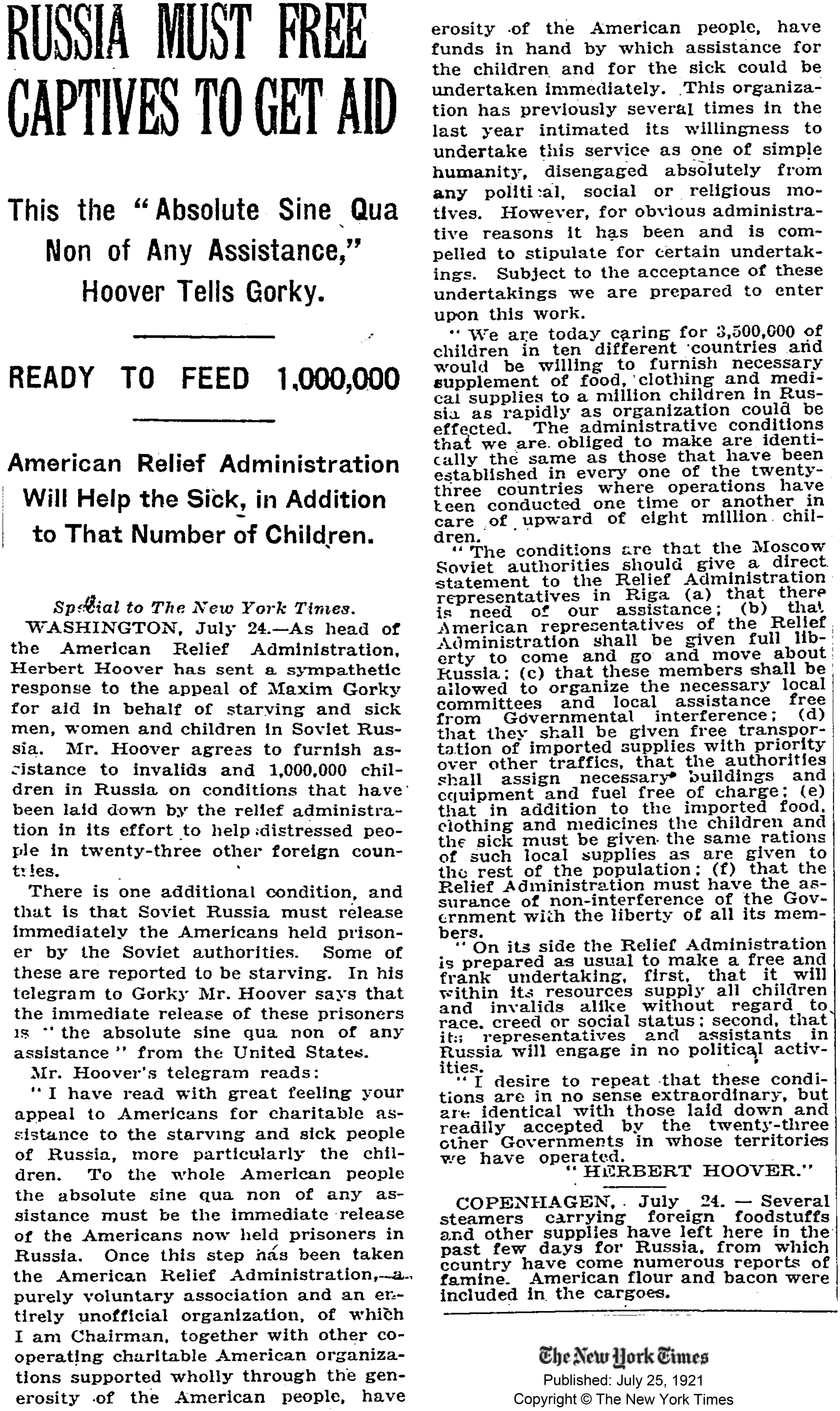

American food relief in Europe, which had been administered since 1919 by the American Relief Administration (ARA), under the chairmanship of Herbert Hoover, was in the summer of 1921 being phased out, though operations were still underway in ten countries involving the support of 3.5 million children. As things stood in July, the ARA had somewhere between $5 million and $7 million available for a mission to Russia.10 The ARA’s internal correspondence in and out of New York headquarters at the time shows the organization preparing for the possibility of a major Russian expedition, a prospect that Hoover, who aside from serving as chairman of ARA was at the time secretary of commerce, discussed with Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes in mid-June. Hoover had seen Gorky’s appeal, or a description of it, in the newspaper on or before July 22, on which date he wrote a note to Hughes asking for permission to respond to it.

You will recollect my conversation of about six weeks ago in which I raised the desirability of extending relief to children and medical relief in Bolshevik Russia. Since that time the food situation has become more difficult, typhus is wider-spread. You may have also noticed the appeals being sent out by prominent Russians including Maxim Gorky for help and the curious statements of the Bolshevik government giving these appeals the color of being unauthorized but that the world is wicked in refusing them. Despite this foolishness, I feel very deeply that we should go to the assistance of the children and also provide some medical relief generally.11

Hoover suggested that, in his capacity as head of the ARA, he cable an offer to Gorky, and enclosed a draft. “I believe it is a humane obligation upon us to go in if they comply with the requirements set out; if they do not accede we are relieved from responsibility.”

Hughes having granted his request, on July 23 Hoover sent Gorky a lengthy and momentous telegram. Gorky’s well-known connections to the Bolshevik leadership led some to believe that in writing his appeal he was acting as a stalking horse for the Soviet government, something that Hoover, in responding to it, took for granted. His message asserted that the ARA, “an entirely unofficial organization,” was prepared to offer assistance, but that a prerequisite for any discussion of famine relief was the immediate release of all American citizens being held prisoner in Russia.12

These Americans had been a subject of controversy for nearly a year, with occasional flare-ups caused by newspaper stories about their alleged mistreatment in Soviet “dungeons.” Hoover himself had been making inquiries about their circumstances and about the possibilities of supplying them with food—inquiries he made through the American Quakers, who maintained a small presence in Moscow. The confirmed number of American prisoners was eight, though there was speculation that there might be more either in confinement or in hiding. These unlucky eight had been arrested for various forms of espionage. The latter term was used rather loosely in 1921 Russia—though in fact the Cheka, the Soviet secret police, had hooked at least one genuine spy, the Baltimore Sun’s Marguerite Harrison, an agent for US military intelligence.13

Were the prisoners issue to be settled, Hoover informed Gorky, the ARA would be prepared to distribute food, clothing, and medical supplies to one million Russian children. Before that could happen, however, “the Moscow Soviet authorities” would have to make a direct application to the ARA. Beyond that, the ARA would insist that certain conditions be agreed to before it embarked on a Russian mission, the same ones enforced in all countries in which it had served. The essential arrangement Hoover proposed was that the Soviet government would allow the ARA the freedom to organize its relief operations as it saw fit, while the ARA would promise to distribute food impartially and stay clear of politics. A July 26 New York Times editorial under the title “Starving Russians,” which lauded Hoover’s response to Gorky’s appeal, closed with the lines,

“If aid is asked it must be accepted on the indispensable terms. These are not peculiar to Russia. As Mr. Hoover points out, his organization applies them to all needy countries alike. Beggars, even if they are haughty Bolsheviki, cannot be choosers.”

Hoover’s telegram was received in Russia on July 26, and two days later Gorky cabled a reply to Hoover, which included the text of the formal acceptance of the ARA’s offer by Politburo member Lev Kamenev. Kamenev proposed that an ARA representative come to Moscow, Riga, or Reval—latter-day Tallinn—to conduct negotiations. Hoover instructed the ARA’s director for Europe, Walter Lyman Brown, to go to Riga. The Soviet government dispatched Deputy People’s Commissar of Foreign Affairs Maxim Litvinov. Negotiations began August 10, the same day the prisoners were released from Russia.14

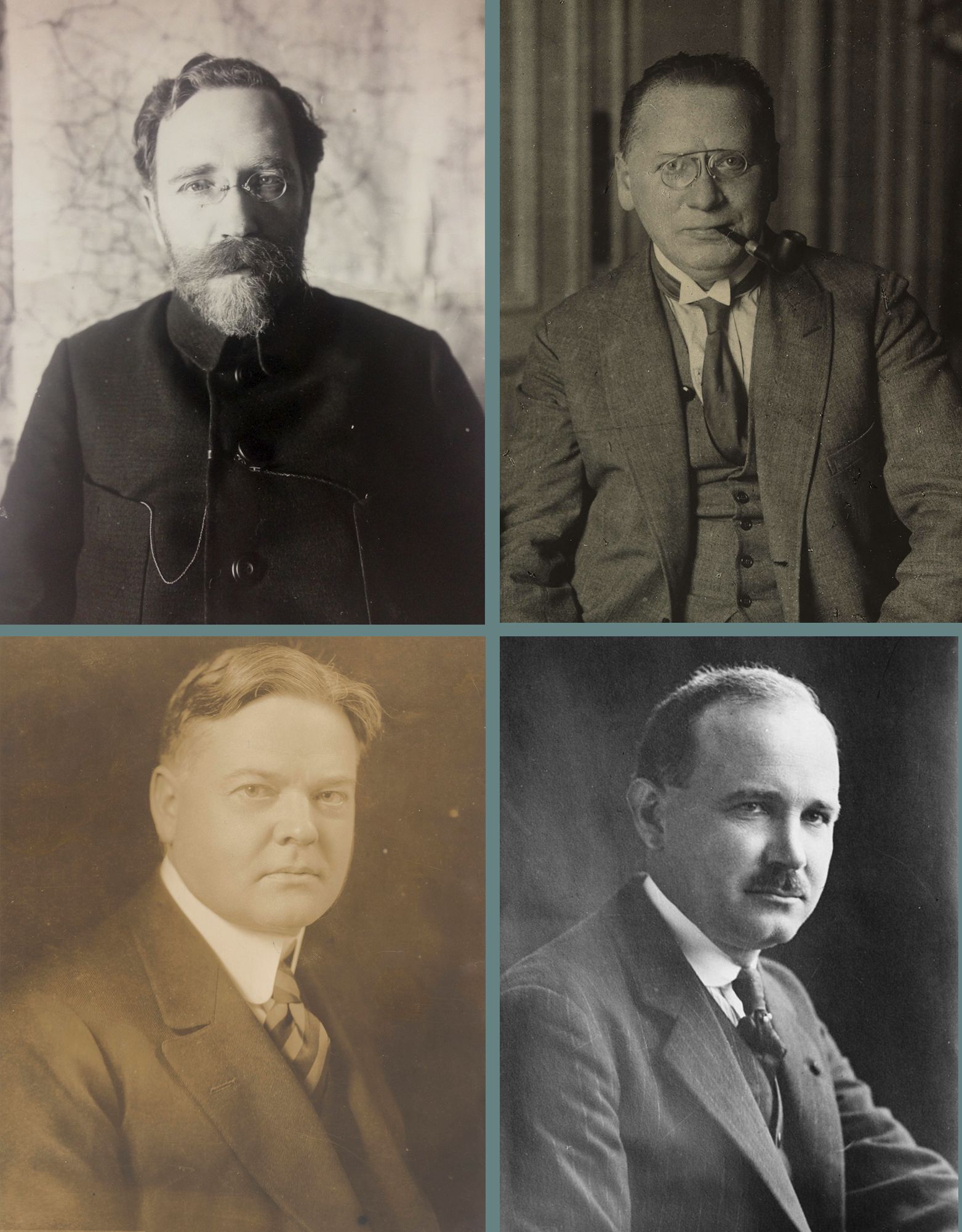

Top row: Lev Kamenev, 1917 (Project 1917) and Maxim Litvinov, 1920 (National Library of Norway). Bottom row: Herbert Hoover, 1917 (ARA Russia) and Walter Lyman Brown, 1900 (Wikimedia Commons).

Top row: Lev Kamenev, 1917 (Project 1917) and Maxim Litvinov, 1920 (National Library of Norway). Bottom row: Herbert Hoover, 1917 (ARA Russia) and Walter Lyman Brown, 1900 (Wikimedia Commons).

Hoover suggested that, in his capacity as head of the ARA, he cable an offer to Gorky, and enclosed a draft. “I believe it is a humane obligation upon us to go in if they comply with the requirements set out; if they do not accede we are relieved from responsibility.”

Hughes having granted his request, on July 23 Hoover sent Gorky a lengthy and momentous telegram. Gorky’s well-known connections to the Bolshevik leadership led some to believe that in writing his appeal he was acting as a stalking horse for the Soviet government, something that Hoover, in responding to it, took for granted. His message asserted that the ARA, “an entirely unofficial organization,” was prepared to offer assistance, but that a prerequisite for any discussion of famine relief was the immediate release of all American citizens being held prisoner in Russia.12

These Americans had been a subject of controversy for nearly a year, with occasional flare-ups caused by newspaper stories about their alleged mistreatment in Soviet “dungeons.” Hoover himself had been making inquiries about their circumstances and about the possibilities of supplying them with food—inquiries he made through the American Quakers, who maintained a small presence in Moscow. The confirmed number of American prisoners was eight, though there was speculation that there might be more either in confinement or in hiding. These unlucky eight had been arrested for various forms of espionage. The latter term was used rather loosely in 1921 Russia—though in fact the Cheka, the Soviet secret police, had hooked at least one genuine spy, the Baltimore Sun’s Marguerite Harrison, an agent for US military intelligence.13

Were the prisoners issue to be settled, Hoover informed Gorky, the ARA would be prepared to distribute food, clothing, and medical supplies to one million Russian children. Before that could happen, however, “the Moscow Soviet authorities” would have to make a direct application to the ARA. Beyond that, the ARA would insist that certain conditions be agreed to before it embarked on a Russian mission, the same ones enforced in all countries in which it had served. The essential arrangement Hoover proposed was that the Soviet government would allow the ARA the freedom to organize its relief operations as it saw fit, while the ARA would promise to distribute food impartially and stay clear of politics. A July 26 New York Times editorial under the title “Starving Russians,” which lauded Hoover’s response to Gorky’s appeal, closed with the lines,

“If aid is asked it must be accepted on the indispensable terms. These are not peculiar to Russia. As Mr. Hoover points out, his organization applies them to all needy countries alike. Beggars, even if they are haughty Bolsheviki, cannot be choosers.”

Hoover’s telegram was received in Russia on July 26, and two days later Gorky cabled a reply to Hoover, which included the text of the formal acceptance of the ARA’s offer by Politburo member Lev Kamenev. Kamenev proposed that an ARA representative come to Moscow, Riga, or Reval—latter-day Tallinn—to conduct negotiations. Hoover instructed the ARA’s director for Europe, Walter Lyman Brown, to go to Riga. The Soviet government dispatched Deputy People’s Commissar of Foreign Affairs Maxim Litvinov. Negotiations began August 10, the same day the prisoners were released from Russia.14

Top row: Lev Kamenev, 1917 (Project 1917) and Maxim Litvinov, 1920 (National Library of Norway). Bottom row: Herbert Hoover, 1917 (ARA Russia) and Walter Lyman Brown, 1900 (Wikimedia Commons).

Top row: Lev Kamenev, 1917 (Project 1917) and Maxim Litvinov, 1920 (National Library of Norway). Bottom row: Herbert Hoover, 1917 (ARA Russia) and Walter Lyman Brown, 1900 (Wikimedia Commons).

As for Gorky, he would depart Russia for Berlin and a convalescence that would turn into eight years of emigration. Stanford historian and Hoover Library curator Frank Golder, during his time serving with the ARA in Soviet Russia in the famine years, recorded evidence of mixed feelings about Gorky among the intelligentsia circles he traveled in. A diary entry for January 13, 1922, records Golder’s conversation with two Petrograd intellectuals, one of them Alexandre Benois (portrait at right), the Russian painter, illustrator, theatrical designer, and leading art historian and critic:

In regard to Gorky. It seems that Gorky regarded himself as the successor of Tolstoy, as the embodiment of Russian art and culture; that he helped to a certain extent the intelligentsiia, but he was always coarse and domineering and turned people against him; that he played a double role, siding at times with the Bolos and other times against them without there being any principle involved. The intelligentsia does not feel any gratitude towards him, but feel that he made a funny, or rather a pathetic, figure as he tried to wear Tolstoy’s boots.15

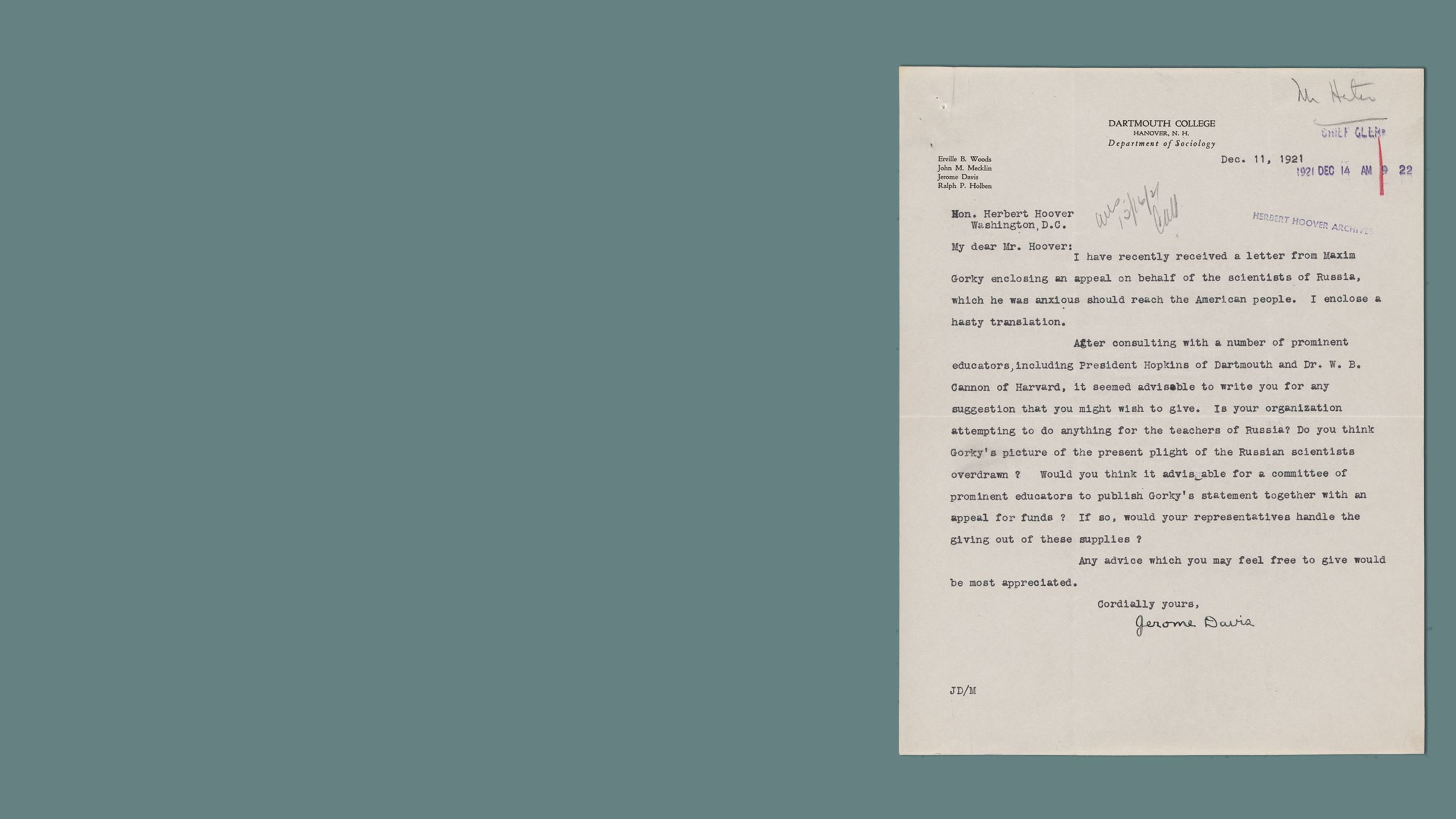

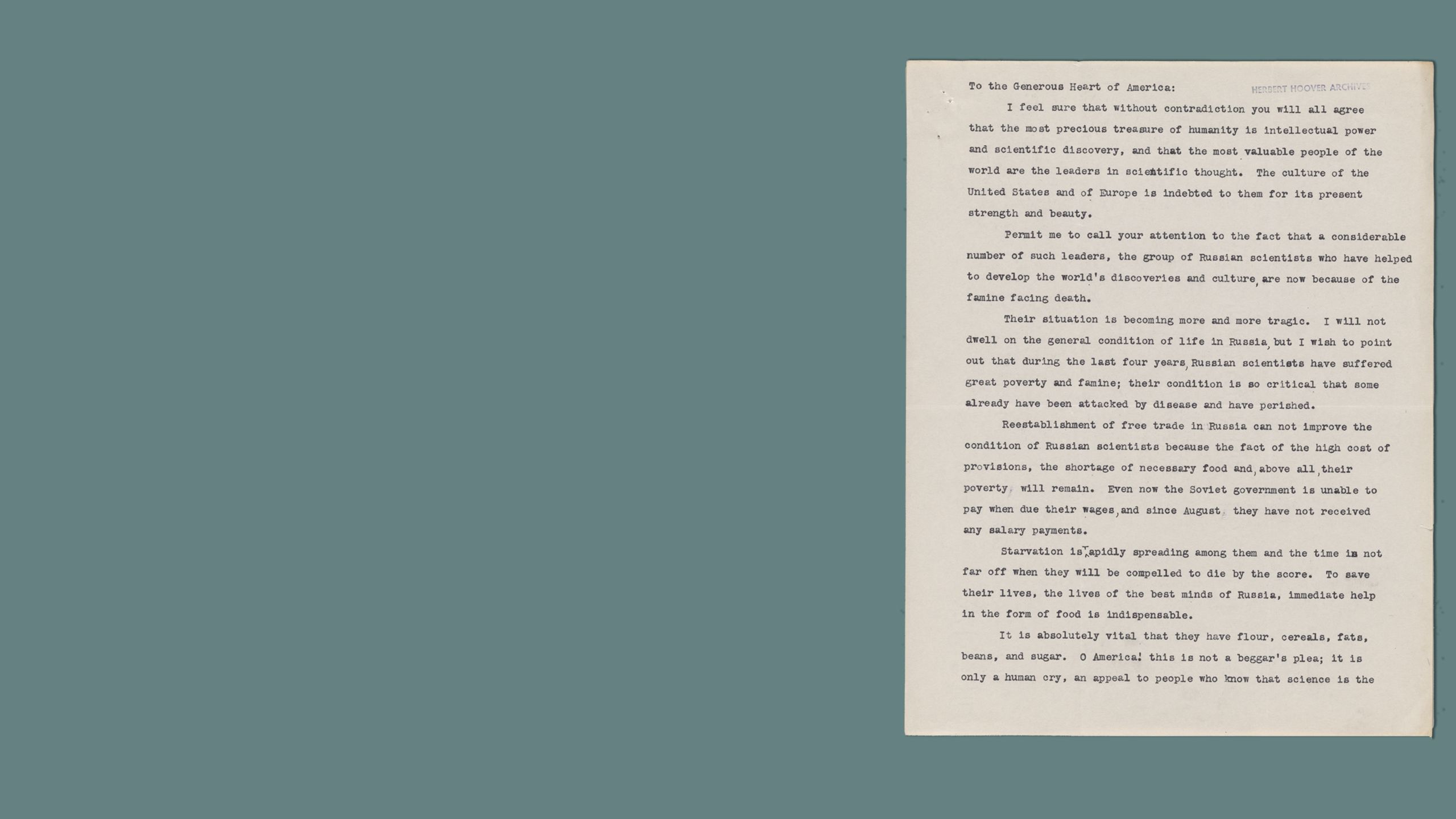

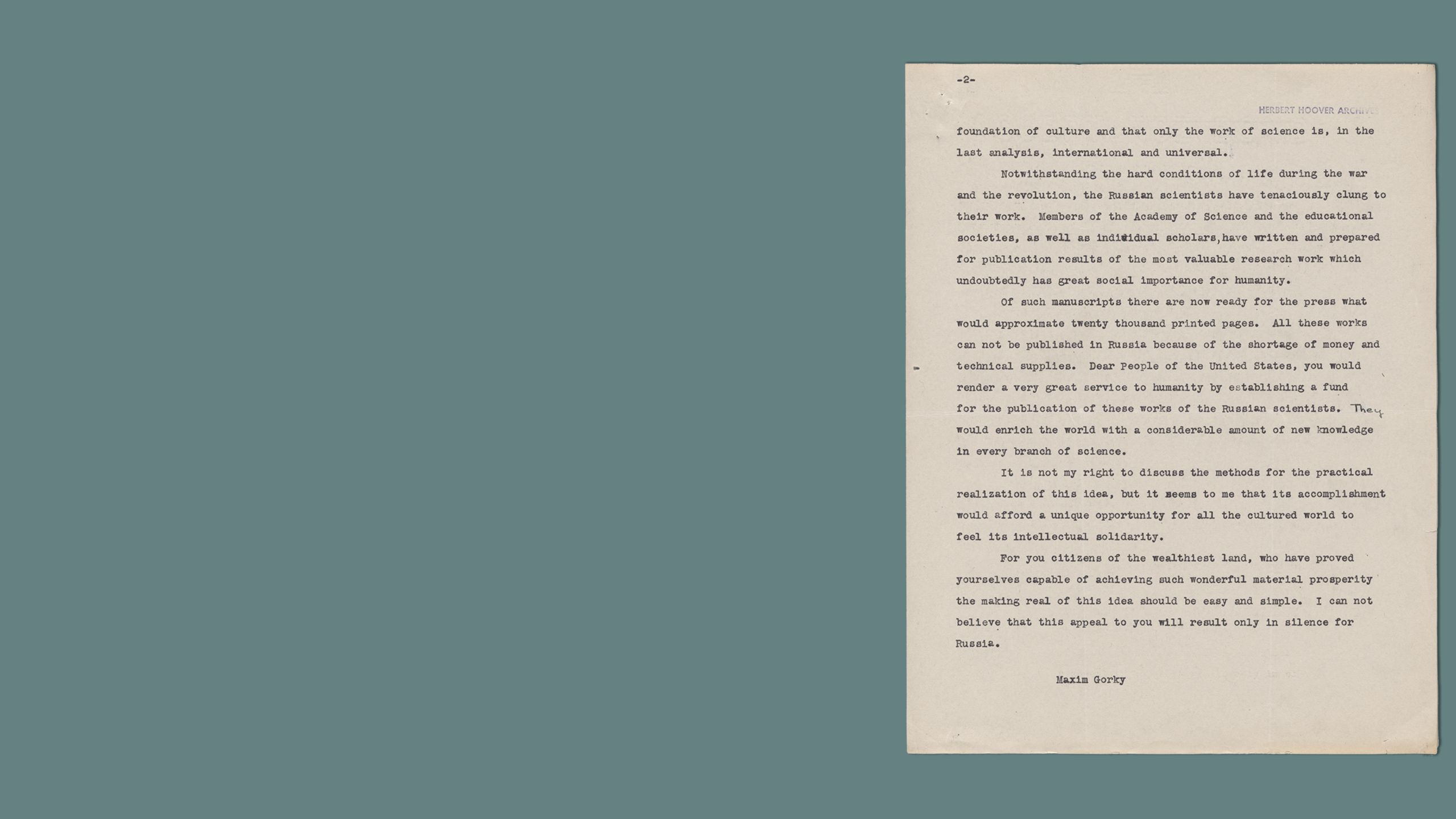

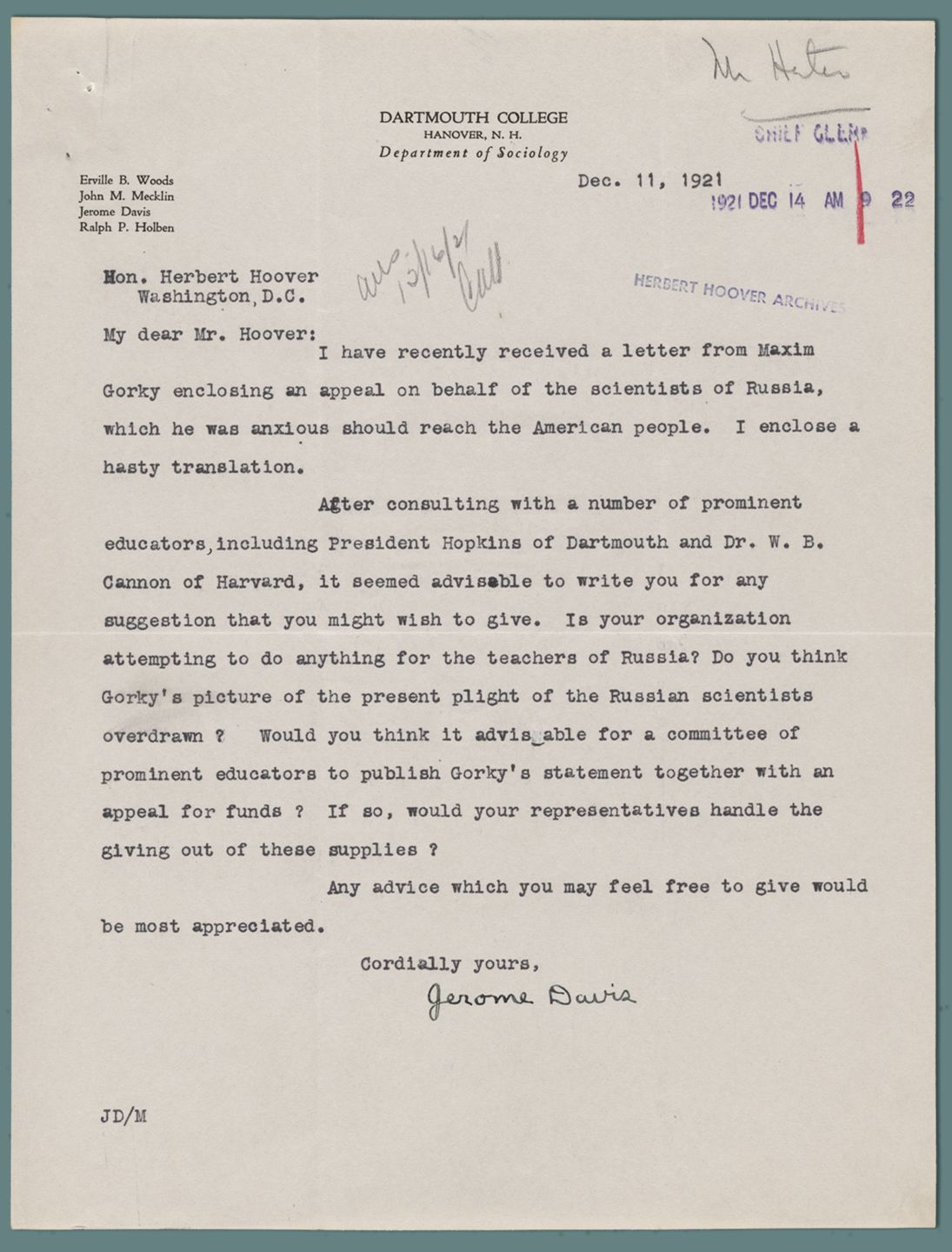

Gorky exited Soviet Russia, but he remained in contact with intellectuals in the capitals and lobbied for relief on their behalf, aided now by Jerome Davis, a sociologist at Dartmouth University who had served in Russia with the YMCA during the war and witnessed the Bolshevik Revolution in October 1917.16

Davis wrote to Herbert Hoover on December 11, 1921, to say that he had recently received a letter from Gorky enclosing an appeal on behalf of “scientists of Russia, which he was anxious should reach the American people. I enclose a hasty translation.” Gorky’s appeal, “To the Generous Heart of America,” stated in part, “O America! this is not a beggar’s plea; it is only a human cry, an appeal to people who know that science is the foundation of culture and that only the work of science is, in the last analysis, international and universal.”17 Hoover's assistant Christian Herter replied to Davis on December 16:

“Mr. Hoover suggests that if you are able to obtain from Mr. Gorky a list of the names and addresses of the Russian scientists in the large cities who are most particularly in need there would probably be little difficulty in taking care of them through food remittances.”18

Davis responded that he would ask Gorky for names and addresses “of scientists who may be in need,” though for some reason months would elapse before the list was forthcoming.19 In the meantime, Davis published an article about the desperate conditions of the intelligentsia, along with the translated text of Gorky’s December 1921 appeal, in the March 1922 issue of the New York Times publication Current History.

On June 3, 1922, Davis wrote to Herbert Hoover to pass along the names and addresses of 211 “scientists” in need of assistance, a list provided to him by Gorky. The ARA arranged for food packages to be sent to 208 of them (three were living in Siberia, out of reach of the ARA). One of the names on Gorky’s list was that of Alexandre Benois.20 On July 30, from Berlin, Gorky wrote a letter to Herbert Hoover, the ARA, and America, expressing gratitude for the gift of ARA food packages to “scientists and men of letters in Moscow and Petrograd.”21 This letter was written one year into the ARA mission, at what turned out to be its halfway mark. In this missive, Gorky reflected on the magnitude of the ARA’s achievement:

In the past year you have saved from death three and one-half million children, five and one-half million adults, fifteen thousand students, and have now added two hundred or more Russians of the learned professions. . . . In all the history of human suffering I know of nothing more trying to the souls of men than the events through which the Russian people are passing, and in the history of practical humanitarianism I know of no accomplishment which in terms of magnitude and generosity can be compared to the relief that you have actually accomplished. . . . The generosity of the American people resuscitates the dream of fraternity among people at a time when humanity greatly needs charity and compassion. Your help will be inscribed in history as a unique gigantic accomplishment worthy of the greatest glory and will long remain in the memory of millions of Russian children whom you saved from death.

As for Gorky, he would depart Russia for Berlin and a convalescence that would turn into eight years of emigration. Stanford historian and Hoover Library curator Frank Golder, during his time serving with the ARA in Soviet Russia in the famine years, recorded evidence of mixed feelings about Gorky among the intelligentsia circles he traveled in. A diary entry for January 13, 1922, records Golder’s conversation with two Petrograd intellectuals, one of them Alexandre Benois, the Russian painter, illustrator, theatrical designer, and leading art historian and critic:

In regard to Gorky. It seems that Gorky regarded himself as the successor of Tolstoy, as the embodiment of Russian art and culture; that he helped to a certain extent the intelligentsiia, but he was always coarse and domineering and turned people against him; that he played a double role, siding at times with the Bolos and other times against them without there being any principle involved. The intelligentsia does not feel any gratitude towards him, but feel that he made a funny, or rather a pathetic, figure as he tried to wear Tolstoy’s boots.15

Alexandre Benois by Leon Bakst (1866–1924), 1898. A black and white reproduction of the original painting from Sovremennyi belet (Contemporary ballet) by Valerian Svetlov, St. Petersburg: Tovarishchestvo R. Golike I. A. Vil'borg, 1911. Hoover Institution Library.

Alexandre Benois by Leon Bakst (1866–1924), 1898. A black and white reproduction of the original painting from Sovremennyi belet (Contemporary ballet) by Valerian Svetlov, St. Petersburg: Tovarishchestvo R. Golike I. A. Vil'borg, 1911. Hoover Institution Library.

Gorky exited Soviet Russia, but he remained in contact with intellectuals in the capitals and lobbied for relief on their behalf, aided now by Jerome Davis, a sociologist at Dartmouth University who had served in Russia with the YMCA during the war and witnessed the Bolshevik Revolution in October 1917.16

Davis wrote to Herbert Hoover on December 11, 1921, to say that he had recently received a letter from Gorky enclosing an appeal on behalf of “scientists of Russia, which he was anxious should reach the American people. I enclose a hasty translation.” Gorky’s appeal, “To the Generous Heart of America,” stated in part, “O America! this is not a beggar’s plea; it is only a human cry, an appeal to people who know that science is the foundation of culture and that only the work of science is, in the last analysis, international and universal.”17 Hoover's assistant Christian Herter replied to Davis on December 16:

“Mr. Hoover suggests that if you are able to obtain from Mr. Gorky a list of the names and addresses of the Russian scientists in the large cities who are most particularly in need there would probably be little difficulty in taking care of them through food remittances.”18

Letter from Jerome Davis to Herbert Hoover, December 11, 1921. ARA Russia, box 323, folder 13.

Letter from Jerome Davis to Herbert Hoover, December 11, 1921. ARA Russia, box 323, folder 13.

Davis responded that he would ask Gorky for names and addresses “of scientists who may be in need,” though for some reason months would elapse before the list was forthcoming.19 In the meantime, Davis published an article about the desperate conditions of the intelligentsia, along with the translated text of Gorky’s December 1921 appeal, in the March 1922 issue of the New York Times publication Current History.

On June 3, 1922, Davis wrote to Herbert Hoover to pass along the names and addresses of 211 “scientists” in need of assistance, a list provided to him by Gorky. The ARA arranged for food packages to be sent to 208 of them (three were living in Siberia, out of reach of the ARA). One of the names on Gorky’s list was that of Alexandre Benois.20 On July 30, from Berlin, Gorky wrote a letter to Herbert Hoover, the ARA, and America, expressing gratitude for the gift of ARA food packages to “scientists and men of letters in Moscow and Petrograd.”21 This letter was written one year into the ARA mission, at what turned out to be its halfway mark. In this missive, Gorky reflected on the magnitude of the ARA’s achievement:

In the past year you have saved from death three and one-half million children, five and one-half million adults, fifteen thousand students, and have now added two hundred or more Russians of the learned professions. . . . In all the history of human suffering I know of nothing more trying to the souls of men than the events through which the Russian people are passing, and in the history of practical humanitarianism I know of no accomplishment which in terms of magnitude and generosity can be compared to the relief that you have actually accomplished. . . . The generosity of the American people resuscitates the dream of fraternity among people at a time when humanity greatly needs charity and compassion. Your help will be inscribed in history as a unique gigantic accomplishment worthy of the greatest glory and will long remain in the memory of millions of Russian children whom you saved from death.

About the Author

Bertrand M. Patenaude, a research fellow at the Hoover Institution, is the author of The Big Show in Bololand: The American Relief Expedition to Soviet Russia in the Famine of 1921 (Stanford University Press, 2002).

This digital story is a component of the Bread + Medicine: Saving Lives in a Time of Famine online exhibition, launched in conjunction with the eponymous exhibition presented by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives, curated by Hoover research fellow Bertrand Patenaude and displayed at Hoover Tower at Stanford University September 19, 2022–May 21, 2023.

Unless otherwise noted, all material comes from the American Relief Administration Russian operational records archival collection at the Hoover Institution Library & Archives [herein abbreviated ARA Russia].

The Hoover Institution Library & Archives has placed copies of these works online for educational and research purposes. If you would like to use any of these works, you are responsible for making your own legal assessment and securing any necessary permission. If you have questions about this resource or have concerns about the inclusion of an item, please contact the Hoover exhibits team.

Contact Us

For more information about rights and permissions please visit

https://www.hoover.org/library-archives/collections/get-help/rights-and-permissions.

© 2023 by the Board of Trustees of Leland Stanford Junior University.