The Female Image in Chinese Propaganda

The New Marriage Law and The White-Haired Girl

“In order to build a great socialist society, it is of the utmost importance to arouse the broad masses of women to join in productive activity. Men and women must receive equal pay for equal work in production. Genuine equality between the sexes can only be realized in the process of the socialist transformation of society as a whole.”

—Mao Zedong, introductory note from Women Have Gone to the Labour Front (1955)

“But I also feel that there are some things that, if said by a leader before a big audience, would probably evoke satisfaction. But when they are written by a woman, they are more than likely to be demolished.”

—Ding Ling, from “Thoughts on March 8” (1942)

Marrying Tradition

The New Marriage Law and Propaganda Under Mao

From effigies of the goddess Roma as a construction of state patronage to Marianne, the personification of the French Republic, women have been used throughout history to signify sociopolitical groups or the authority of the state itself. Depictions of women in the early Chinese Communist Party (CCP) regime were no exception. The state’s rudimentary feminist discourse translated itself through the images of women into private contexts, and with the production of propaganda posters, depictions of ordinary citizens allowed the regime to seamlessly appropriate the public.

When the People’s Republic of China was established in 1949, marriage reform was one of the new regime’s first priorities. Previously, marriages had often been arranged, concubinage was commonplace, and women were unable to seek divorce. While women’s rights had been a major concern of the New Culture Movement in prior decades, the CCP had occasionally compromised with patriarchal rural practices in order to maintain the support of peasants during the Sino-Japanese War and Chinese Civil War. However, the New Marriage Law, enacted in May 1950, set up the standard of “freedom of marriage” for both men and women, a dramatic departure from marriages arranged on the basis of prerevolutionary family interests. Nevertheless, the law encountered violent local resistance in heterodox rural areas, necessitating yearly propaganda campaigns on the part of the newborn regime.

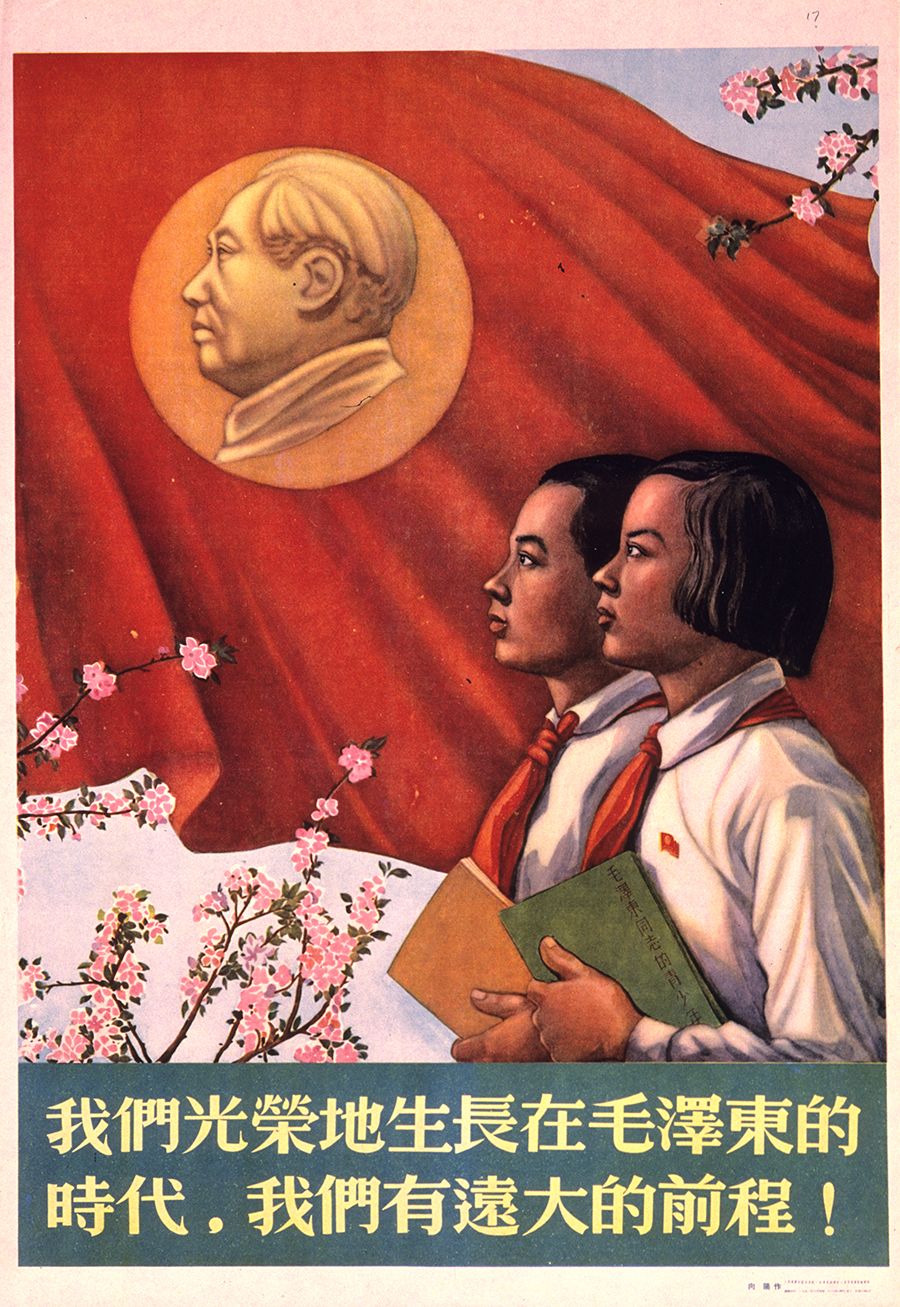

We live a glorious life in Mao Zedong’s era, we have a great future, by Yang Xiang, issued by People’s Arts Publishing House, circa 1951. Poster Collection, CC 126, Hoover Institution Archives

We live a glorious life in Mao Zedong’s era, we have a great future, by Yang Xiang, issued by People’s Arts Publishing House, circa 1951. Poster Collection, CC 126, Hoover Institution Archives

As part of the ongoing propaganda campaign, Bi Cheng’s Marriage of self-choice and working together to bring about happiness was released in February 1953. The use of text is limited, with a simple two-part message designed to be easily understood by a rural audience. Mao Zedong had proposed the concept of “love matches” as a replacement for traditional arranged marriages, and it was during this period that the term airen, or “love partner,” was introduced. The wedded peasants stand together, with neither significantly raised above the other, demonstrating equality guaranteed by the new law, while the lower half of the frame is taken up by abundant crops, representing the productive power of their marriage.

Mao Zedong’s opposition to arranged marriages was undoubtedly profound. His own first marriage had been arranged for him at the age of 14, and as early as 1919, Mao expressed condemnation of a marital system “capable of killing men as well as women” in his writings on Miss Chao’s Suicide. However, under Mao, class categories of “red,” “ordinary,” and “black” households remained fixed by the status of the male household leader and were inherited through the male line. This not only had a major effect on marital choice for citizens, as preference was shown to the “red” revolutionary and proletarian households by the regime, but was also a patriarchal formation that had no foundation in Marxist theory.

Further, despite his egalitarian rhetoric, Mao himself had invited criticism for sexism. In essays published in Yan’an, the writer Ding Ling criticized the party’s shabby treatment of women, and Wang Shiwei noted the pursuit of young women by married cadres, who neglected older wives who had been revolutionary comrades for many years. This had incensed Mao, who had recently abandoned his wife from the Jiangxi Soviet for a young actress from Shanghai, Jiang Qing. Denounced for disrupting party unity, Wang Shiwei was expelled and imprisoned.

Marriage of self-choice and working together to bring about happiness, by Bi Cheng, issued by the People’s Arts Publishing House, circa 1953. Poster Collection, CC 161, Hoover Institution Archives

Marriage of self-choice and working together to bring about happiness, by Bi Cheng, issued by the People’s Arts Publishing House, circa 1953. Poster Collection, CC 161, Hoover Institution Archives

The White-Haired Girl

A Classic Cultural Production

In 2015, China’s Ministry of Culture announced a revival to one of the CCP’s most classic cultural productions, the revolutionary opera titled The White-Haired Girl. Accompanying this announcement, the ministry stated, “This is concrete action to implement General Secretary Xi Jinping’s important speech and opinions on art and literature. . . . The revival of the opera The White-Haired Girl, under new conditions, and its widespread dissemination, has major practical significance and far-reaching historical significance.”

Though it would later be performed in major cities across China, including Beijing, the revival’s premiere in Yan’an was a resonant affair. The White-Haired Girl had been performed for the first time in Yan’an, during the Seventh National Congress of the Communist Party of China. The narrative had originated as a piece of folklore in Hebei province, which had been occupied by the CCP’s Eighth Route Army in the late 1930s, before being adapted into the opera by He Jingzhi alongside a team of writers and composers.

After its first performance, in 1945, The White-Haired Girl was further adapted into both a film and ballet production. It was again renewed in importance in the 1960s as one of the Eight Model Operas approved by Jiang Qing during the Cultural Revolution, alongside mainstays such as The Red Detachment of Women. During this time, it was acclaimed as an example of “shining Mao Zedong Thought” for its portrayal of workers, peasants, and soldiers as the protagonists of history. In the years following the Cultural Revolution, however, model theater was somewhat tainted by its political context: Chen Sihe commented that it had an “abominable effect” on Chinese literary creativity. Nevertheless, the opera continued to be performed; Xi Jinping’s wife, Peng Liyuan, notably received the Plum Blossom Award for her portrayal of Xi’er in a 1980s production. For the 2015 revival, she served as artistic director, guiding revisions to the new performance.

New York Times journalist Chris Buckley commented about that revival that such “entanglement of a party leader and his spouse in determining artistic values through a ‘model opera’ might bring disquieting echoes of the past,” in reference to how Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing, had also sung parts of the opera and oversaw its ballet adaptation. However, other commentators emphasized that it was unlikely for The White-Haired Girl to resonate with the aesthetic palates of younger Chinese audiences, though it was likely to evoke nostalgia with the older population. During the years in which model operas dominated China’s cultural milieu, some would joke that “eight hundred million people watched eight shows.”

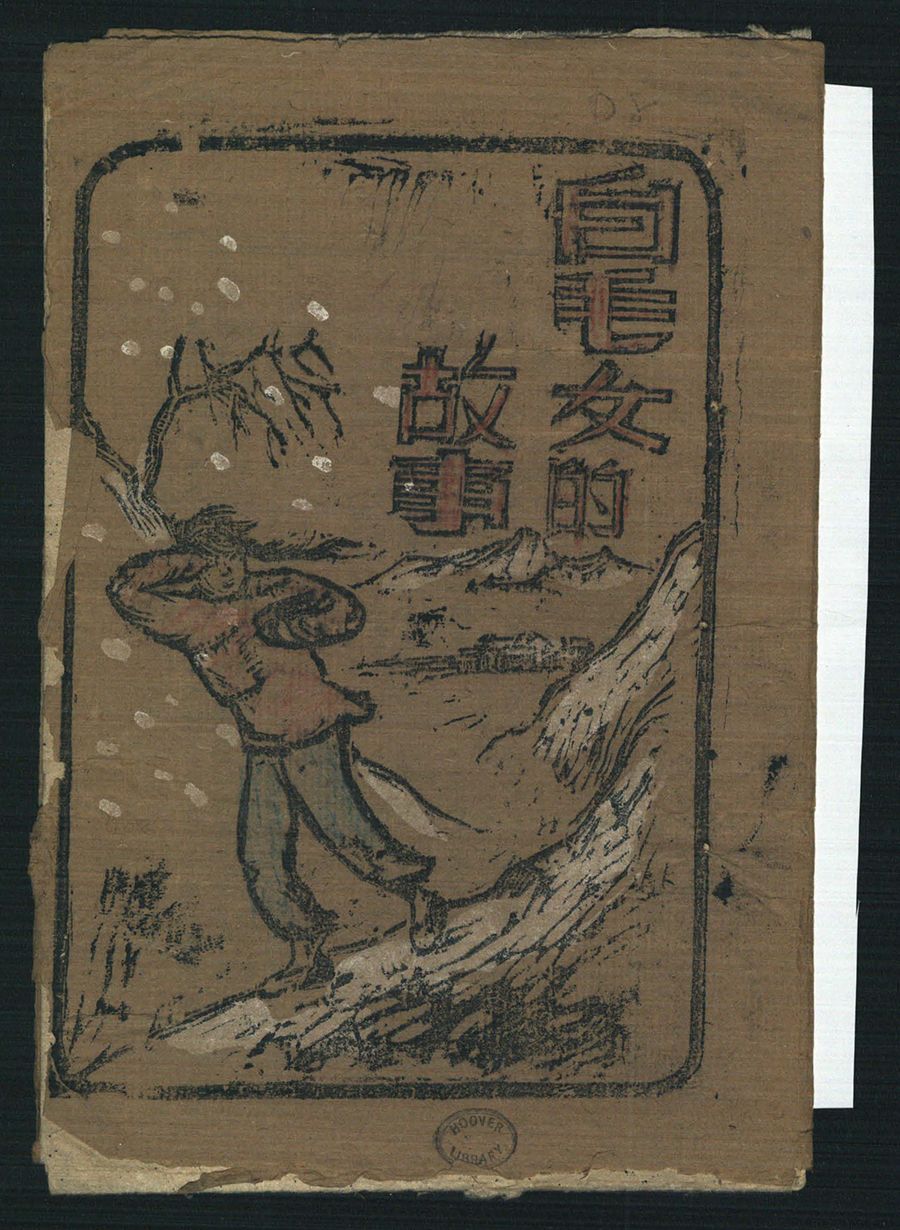

The Story of the White-Haired Girl, issued by Luyi Cultural Supply Company, circa 1934. Hoover Institution Library

The Story of the White-Haired Girl, issued by Luyi Cultural Supply Company, circa 1934. Hoover Institution Library

The Story of the White-Haired Girl, issued by Luyi Cultural Supply Company, circa 1934. Hoover Institution Library

The Story of the White-Haired Girl, issued by Luyi Cultural Supply Company, circa 1934. Hoover Institution Library

The Story of the White-Haired Girl, issued by Luyi Cultural Supply Company, circa 1934. Hoover Institution Library

The Story of the White-Haired Girl, issued by Luyi Cultural Supply Company, circa 1934. Hoover Institution Library

The Story of the White-Haired Girl, issued by Luyi Cultural Supply Company, circa 1934. Hoover Institution Library

The Story of the White-Haired Girl, issued by Luyi Cultural Supply Company, circa 1934. Hoover Institution Library

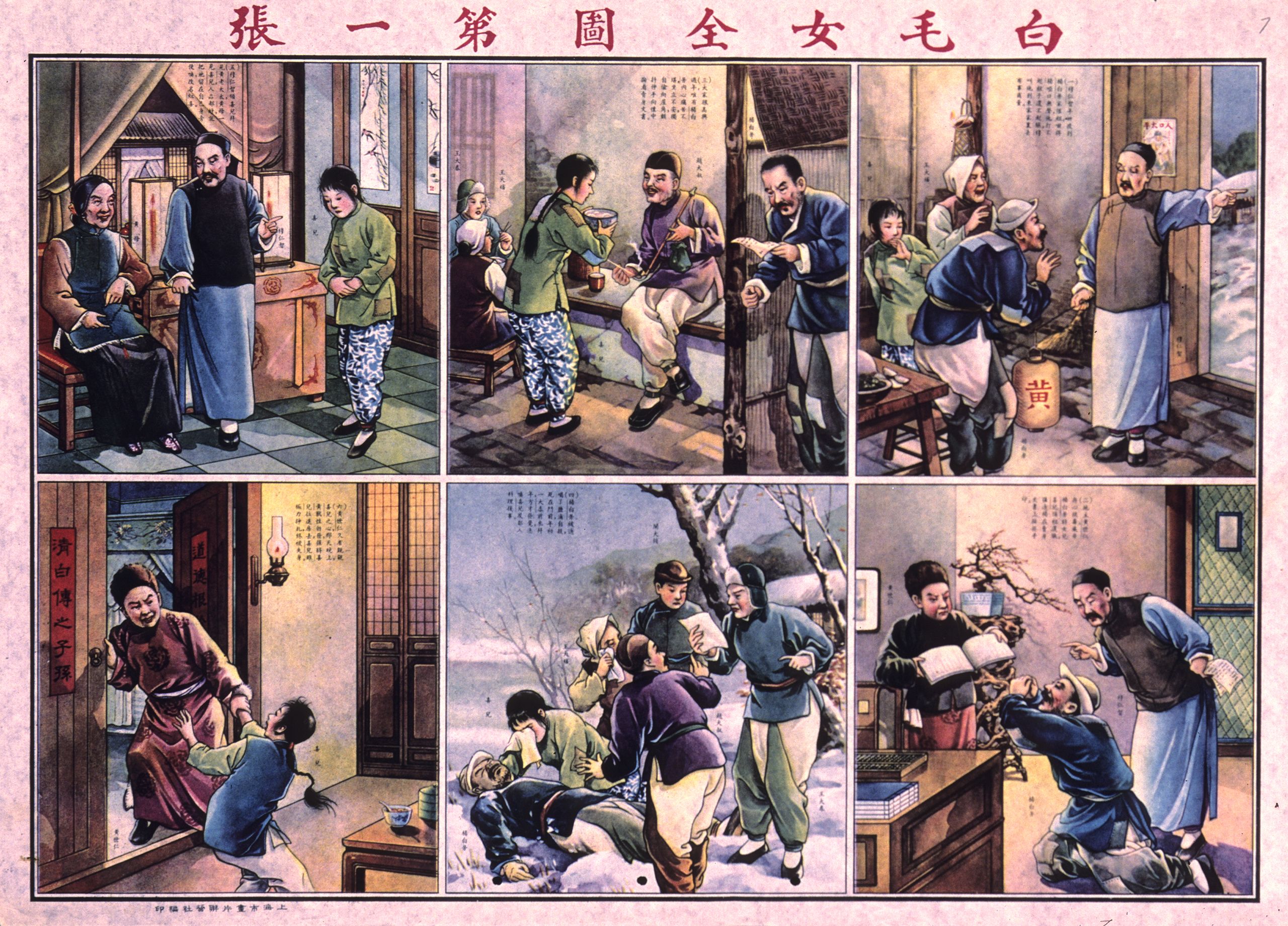

First part of the story of the white-haired girl, issued by Shanghai Picture Printing Joint Company, circa 1949. Poster Collection, CC 36, Hoover Institution Archives

First part of the story of the white-haired girl, issued by Shanghai Picture Printing Joint Company, circa 1949. Poster Collection, CC 36, Hoover Institution Archives

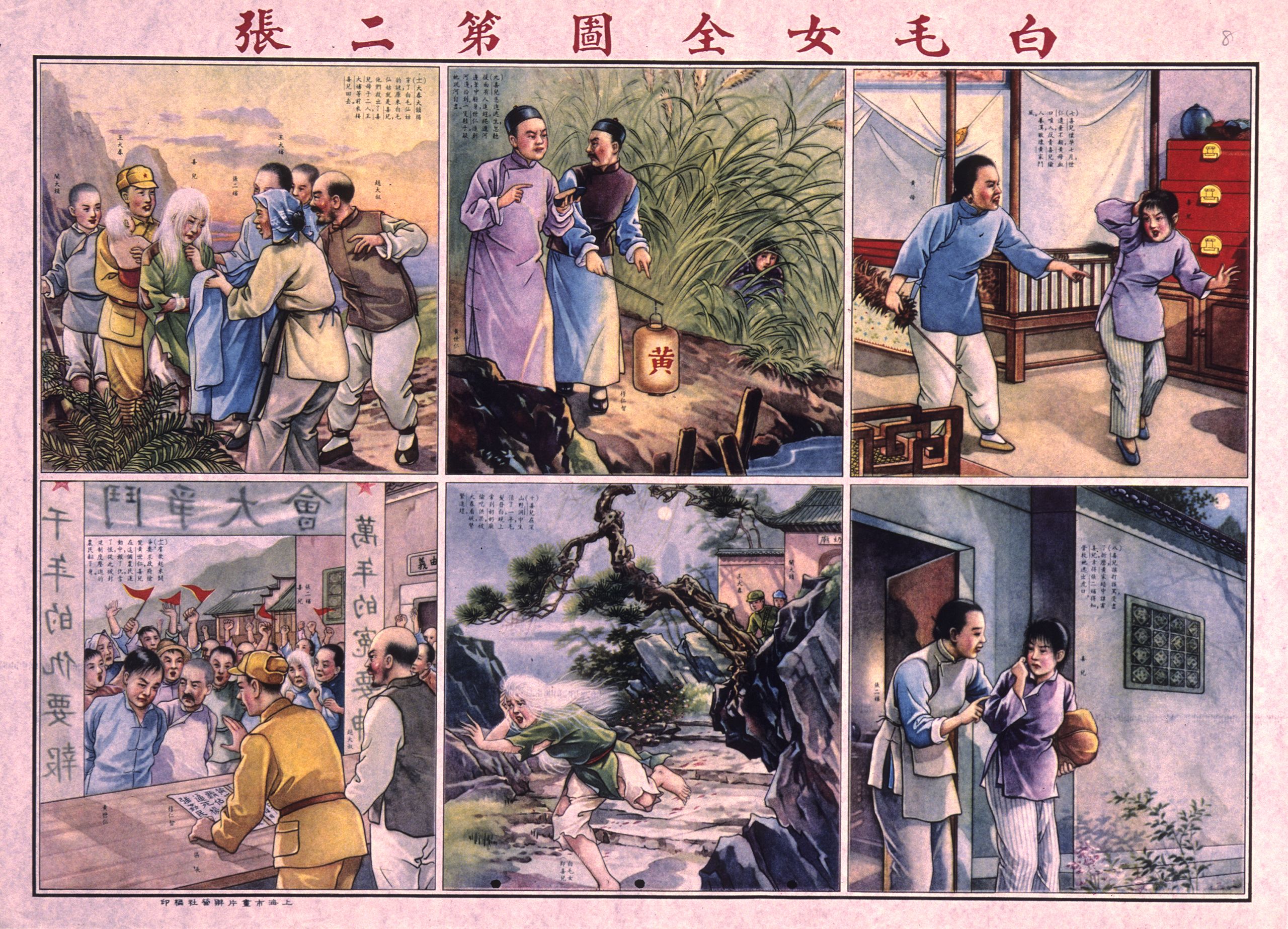

Second part of the story of the white-haired girl, issued by Shanghai Picture Printing Joint Company, circa 1949. Poster Collection, CC 37, Hoover Institution Archives

Second part of the story of the white-haired girl, issued by Shanghai Picture Printing Joint Company, circa 1949. Poster Collection, CC 37, Hoover Institution Archives

In Hebei, local tales spoke of ghostly women who had developed white hair as a consequence of their great suffering, who lived in the wilderness following the loss of their family. However, following appropriation of the tale by the Chinese Communist Party, this ending would be amended from tragedy to emancipation.

One version of the narrative goes thus: We are introduced to a hardworking peasant girl named Xi’er and her father, Yang Bailao. Unfortunately, a landlord named Huang Shiren abducts her as payment for her father’s debts, and her father commits suicide shortly thereafter. She becomes pregnant as a consequence of Huang’s abuse and eventually flees into the wilderness. During her isolation, her hair turns white and locals begin to believe that she is a ghost or a goddess. Fortunately, Wang Dachun, a young farmer in her village who has joined the army unit, proceeds to liberate her, and her landlord is exposed for his crimes. She is reunited with her fiancé in mutual class feeling, as she calls him “comrade,” and they lead a happy life after emancipation, her hair returning to black.

The opera was intended to be revolutionary in both form and content. Though Xi’er herself originated from local folklore, the opera merged Western influence with traditional forms from northern China. Nonetheless, the central conflict within this version is structured not around Xi’er but men, as authority over her passes from her father to Huang Shiren, then to Wang Dachun. The vivid message is simple. Whereby Xi’er’s body becomes the site of class struggle between Wang Dachun and Huang Shiren, the old feudal society had turned humans into ghosts, while the Communist revolution returns such ghosts to humanity.

At the time of its initial performance, the Chinese Civil War had not yet ended. The White-Haired Girl was an expression of hope for the guerrillas nestled in the Yan’an stronghold, for a future that might yet come.

CD cover of The White-Haired Girl, conducted by Fan Shengwu, performed by the Shanghai Ballet Orchestra. Published by Yellow River Chinese, 2004. Stanford University Naxos Music Library

CD cover of The White-Haired Girl, conducted by Fan Shengwu, performed by the Shanghai Ballet Orchestra. Published by Yellow River Chinese, 2004. Stanford University Naxos Music Library

However, other versions differed significantly. Decades later, in the Cultural Revolution ballet version of The White-Haired Girl, revised under Jiang Qing, Xi’er ends by picking up a gun and joining the ranks of the Eighth Route Army to carry on the eternal revolution of the proletariat. The 2015 stage revival of the opera featured 3D visual effects, and thirty thousand Chinese citizens viewed performances in major cities such as Guangzhou, Changsha, Hangzhou, Shanghai, and Beijing. Yet regardless of the decade, such forms of literature sought to reproduce state policies and enter them into civic cultural contexts; in this project, the state’s discourse might translate itself through the female image into private life.

The White-Haired Girl, directed by Wang Bin and Shui Hua. Published by Changchun Film Studio, 1950. Public domain

Bibliography

Andrews, Julia Frances. Painters and Politics in the People's Republic of China, 1949–1979. Berkley: University of California Press, 1994.

Bai, Di. “Feminism in the Revolutionary Model Ballets: The White-Haired Girl and The Red Detachment of Women.” In Art in Turmoil: The Chinese Cultural Revolution 1966–76, edited by Richard King, 188–202. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press, 2010.

Buckley, Chris. “‘White-Haired Girl,’ Opera Created under Mao, Returns to Stage.” Sinosphere (blog), New York Times, November 10, 2015. https://sinosphere.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/11/10/white-haired-girl-opera-created-under-mao-returns-to-stage.

Cong, Xiaoping. Marriage, Law and Gender in Revolutionary China, 1940–1960. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

Farley, James. Model Workers in China, 1949–1965: Constructing a New Citizen. London: Routledge, 2019.

Flath, James. “‘It’s a Wonderful Life’: Nianhua and Yuefenpai at the Dawn of the People's Republic.” Modern Chinese Literature and Culture 16, no. 2 (Fall 2004): 123–59.

Hung, Chang-tai. “Oil Paintings and Politics: Weaving a Heroic Tale of the Chinese Communist Revolution.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 49, no. 4 (October 2007): 783–814.

Phillips, Tom. “China Heralds New Tone for the Arts With 3D Film of Revolutionary Opera.” The Guardian, December 28, 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/dec/28/china-arts-the-white-haired-girl-film-revolutionary-opera-mao-zedong.

Walder, Andrew G. China under Mao: A Revolution Derailed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015.

Yue, Meng. “Female Images and National Myth.” In Gender Politics in Modern China: Writing and Feminism, edited by Tani Barlow, 118–36. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1994.

About the Author

Sharon Du is an undergraduate junior at Stanford University majoring in international relations. Her honors thesis examines interactions between propaganda variants in mainland China. She is from Melbourne, Australia, and is a puppy-dog enthusiast.

About the Hoover Institution Student Fellowship

The Hoover Student Fellowship Program offers Stanford students a unique opportunity to engage in important work at the Hoover Institution across research and organizational areas. The Fellowship is a paid internship in which students are paired in topical areas of their preference with Hoover fellows or staff members. Students in the Fellowship provide research and operational support, while also benefiting from mentoring and partaking in enriching programming for the Fellowship cohort. The Hoover Institution Library & Archives is proud to sponsor students in the Fellowship. Learn more...

The Hoover Institution Library & Archives has placed copies of these works online for educational and research purposes. If you would like to use any of these works, you are responsible for making your own legal assessment and securing any necessary permission. If you have questions about this resource or have concerns about the inclusion of an item, please contact the Hoover exhibits team:

Contact Us

For more information about rights and permissions please visit,

https://www.hoover.org/library-archives/collections/get-help/rights-and-permissions.

© 2022 by the Board of Trustees of Leland Stanford Junior University.